Czech Republic: Four concentration camps for Roma ran during WWII in Liberec - Part Three

This is the final piece in our three-part series about the concentration camps for Romani people in Liberec that ran from 1939 until 1943 when the country was the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The series is based on articles by Ivan Rous in the books “Camps and Wartime Production” (“Tábory a válečná výroba“) and “Blank Spaces in Holocaust Research” (“Bílá místa ve výzkumu holokaustu“).

This last article discusses a camp that was run in a privately-owned building in Horní Růžodol. It also discusses the fourth such facility, a building constructed especially to intern Romani prisoners on Kunratická Street.

The “U lomu” (At the Quarry) camp for Romani prisoners on Kunratická Street

On 7 November 1940 a meeting was held by the Liberec City Council, and one item on the agenda was the establishment of the “gypsy barracks” – a camp for 130 Romani prisoners. The minutes of that meeting are the first time that the number of persons to be located in the barracks is mentioned, as is the location of another camp for Romani prisoners in Liberec.

In addition to factory building number 120, it is stated in the minutes that Romani people were also being accommodated in a dilapidated, privately-owned building in Horní Růžodol. However, no building number or any other information is mentioned about that facility.

The barracks were to be built according to plans for Kunratická Street using a budget of 10 000 Reichsmarks and using materials acquired from the Watzekov house on Frýdlantská Street. Other correspondence about them concerns preparing the building permits, which was done on 19 November 1940 on the condition that the materials would be acquired from the demolition of properties owned by the City of Liberec.

The building was to have been completed as of 31 March 1941. From the attached description of the construction we can learn many details.

The one-story construction had a gabled roof covered with tar paper. The building was divided into a daytime room of 96 square meters, a sleeping room of 338 square meters, and a laundry room of 10.2 square meters.

The building was equipped with two stoves in the sleeping section, two cookers in the daytime room and a boiler in the laundry room. Toilets were located outside the building and potable water was to be drawn from the slope above Kunratická Street, specifically, from lot number 1349.

In addition to materials from the Watzekov house, materials from the factory formerly owned by Franz Liebeig in the village of Vesce were also to be used. The Office of the Governing President in Ústí nad Labem was contacted several times by Mayor Rohn about establishing the camp for Romani prisoners.

At the end of November, the mayor urgently demanded approval of the construction, arguing that he had to save “[his] German population from the Gypsies”. The conditions where they were living at the time, according to Rohn, were unsustainable, neighbors were reportedly complaining about the presence of the Romani prisoners, and he had to “move the Gypsies to a less built-up area, with a heavy heart”.

The complaints in this case concerned the camps for the Romani prisoners that had been set up by the city in Horní Růžodol and in Rochlice, where they were being accommodated in cruel conditions. In December 1940, the approval of the construction of the barracks was granted by the Office of the Governing President in Ústí nad Labem and the construction materials began to be ordered.

In March 1941 a dispute flared up between the office of Mayor Rohn and the State Road Construction Authority. The essence of the dispute was the distance of the barracks from the road, which was 8.5 meters when it should have been a minimum of 22.5 meters.

Thanks to this error, the Road Authority was refusing to grant permission for the site. What is interesting about the entire dispute is the statement of Mayor Rohn from 20 March 1942, where it is written that “the barracks naturally represent just one phase of the solution”.

The dispute was eventually dealt with through the Office of the Governing President and lasted until June of 1941. By the end of July 1941 the basic construction had been completed.

On 11 August 1941 the workers left the construction site, and on 22 August the building was issued a use permit, of course on the condition that it would only be possible to use it during the warm months of the year, otherwise brick chimneys would have to be installed. Those conditions were not met, and a report from November 1942 states that the benches and tables in the barracks had been burned for fuel and that the stovepipe still simply led out through the tar-paper roof.

The records also show that the mayor asked the tax authorities not to levy any real estate tax against the property. Approximately 130 Romani prisoners were moved into the barracks on 15 August 1941.

While a summary of the information about the population of the camp was probably kept by police, it has yet to be discovered. It is also possible that after the prisoners were deported to concentration camps elsewhere that the records were destroyed.

In the files that do exist, just two reports have been preserved about life at the camp. The first is a confirmation of a request made by a Franz Bernhardt, born 5 March 1888 in Dreihunken (Teplice district) and by an August Richter, born 2 May 1874 in Lick (western Prussia) for the Building Police to approve the parking of a caravan outside the barracks as long as the state police had no objections.

Franz Bernhardt was probably a leading figure within the Romani collective, judging by his quite confident communications with the authorities in the Nazi German environment. The second report on file is from 4 March 1942, when Alfred Kraus, a Romani man, caused 10 reichsmarks worth of damage to the doors of the barracks and was sentenced to one month in prison.

There are no other mentions of Romani people in Liberec at this time known to date, and the events can be reconstructed only on the basis of eyewitness testimonies for the time being. Records show that on 12 March 1943 the Community of German Crafts, specifically, the Fellowship of Building Trades, asked that the already-empty barracks be given to it.

By 1943 the Romani prisoners had already been transported to concentration camps elsewhere. The barracks of the defunct camp later served for the accommodation of foreign laborers.

On 10 April 1943 there was an inspection of the facility. The record of the inspection describes the necessity of adding accommodations for a camp commander and for an administrator of the barracks.

Two temporary wartime houses, numbers 576 and 577, were built for that purpose on lots numbered 710 and 710/2. House number 576 is still standing there to this day.

In October 1943, the Gustav Mölder firm, a wholesaler in wool, asked to lease the camp barracks for use as a warehouse for waste wool. That letter expressly refers to the barracks in Liberec-Starý Harcov, which corresponds to the two barracks built in 1939 above the quarry.

The city agreed to the proposal. However, because there is correspondence missing, it is not possible to determine whether this was about the barracks on lot 1350/2 built in 1941, or about the older barracks from 1939.

Conclusion

In Liberec there were four facilities that can be considered to have been camps for Romani prisoners, even though during the official correspondence of the day, with only a few exceptions, these facilities were referred to as “Gypsy accommodations”. The first camp was connected with the exploitation of Romani labor by the J.W. Roth firm for the construction of the Domov housing estate in Králův Háj, and probably involved the use of two wooden barracks in Kunratická Street on the grounds of the present-day quarry.

That facility was probably used just during the autumn of 1939. The second camp was a building owned by the Textilana A.G. firm at number 120 on Nádražní Street, where Romani prisoners were located from the end of 1939 until the barracks situated in the curve of Kunratická Street were completed.

Around 80 individuals were accommodated in that second camp. The third camp was located in a “privately-owned building” in Horní Růžodol, but we do not know which building that was.

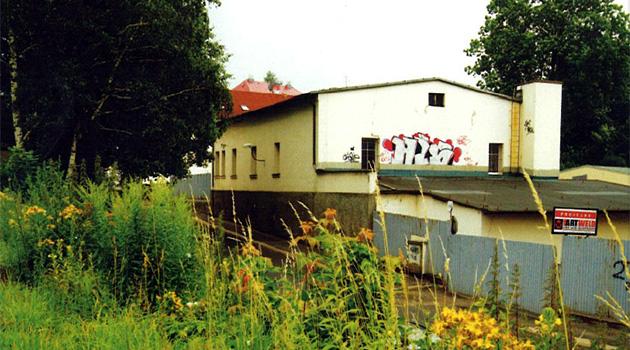

The fourth camp facility, which is also referred to in the documents of the day by the term “concentration camp”, was comprised of the barracks built especially for the purpose of interning the Romani prisoners. That was located in the curve of Kunratická Street near the quarry.

Between the summer of 1941 and the spring of 1943, 130 Romani prisoners were interned there. Later in the war in served to accommodate people from France, and in 1962 it is drawn on the cadastral map as a ruin.

With the exception of a few bits and pieces, we do not know what daily life was like for the Romani people in the Liberec camps. We have also not yet discovered a list of those deported from Liberec to the concentration camps elsewhere either.

Based on eyewitness testimonies, it is possible to assume that the vast majority of Romani people interned in the concentration camps did not survive. Last but not least, the almost purely technical descriptions that remain of the buildings used in Liberec for the internment of the Romani prisoners should serve as a warning of how understated the official steps were that led to the civilian-sounding “accommodation of Gypsies” prior to their mass murder in the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

We thank the author for his kind permission to publish these excerpts of his texts.