Czech Republic: Four concentration camps for Roma ran during WWII in Liberec - Part Two

This is the second piece in our three-part series about the concentration camps for Romani people in Liberec that ran from 1939 until 1943 when the country was the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The series is based on articles by Ivan Rous in the books “Camps and Wartime Production” (“Tábory a válečná výroba”) and “Blank Spaces in Holocaust Research” (“Bílá místa ve výzkumu holokaustu”).

This article is about the Textilana firm, the headquarters of which was on Nádražní Street. A building owned by that firm served as a concentration camp for Romani forced laborers.

The camp for Romani prisoners on Nádražní Street

The camp was located directly inside the factory building at number 120. The facility was first constructed by Jacob Ilchmann in 1869 as a textile factory.

In 1889, construction repairs were done to the factory and a steam engine was installed. The owner at that time was August Ehrlich.

The next reconstruction was performed in 1906 by owner Anton Schlenz, and in 1909 the factory was bought by the firm Reichenberger Modewarenfabrik G.m.b.H., which belonged to a J. Mareš and a J. Hliňák. On 4 April 1933, the Textilana A.G. firm, headquartered in Chrastava, bought the building.

For the years 1934-1938 there are no documents at all in the construction archive of the City of Liberec. The first mention of the building from 1939 concerns those who are looking for a site for a camp for Romani forced laborers.

The initiator was the Roth firm, which was exploiting Romani families for construction work at the time. In those days, naturally, this was a form of labor camp.

On 5 December 1939 an inspection of building no. 120 was allowed. Part of the invitation to the inspection is a form issued by the City of Liberec and used to catalog abandoned buildings, where the campus of the factory is described briefly.

The invitation to the inspection also included a report from 4 December 1939 that very well describes the circumstances of the creation of the camp for Romani laborers in the factory building in the Rochlice municipality. In its entirety, it reads as follows:

“On Saturday, 25 November 1939, at around 11 AM, Mr Kratochwil from the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (DAF) came to the Building Police Office and announced that an inspection was being held of the ‘Textilana’ – the factory in Rochlice at number 120 – because gypsy families working on the construction of the Königsbusch housing estate were to be located there.

Mr Kratochwil’s visit was recorded by the Construction Director; Mr Kratochwil also visited the mayor and asked both gentlemen to provide resources for the most

necessary repairs to the factory, but High Inspector Rau of the State Police and the District Head of the police station at Rochlice agreed that the accommodation of the Gypsies must be taken care of by the social office together with the firm employing the people.

The mayor allowed, at the intercession of the Construction Director, for one mason to perform the repairs, and then Municipal Site Manager Hübner was sent to Rochlice to supervise the work, especially to see whether a mason had been prepared for the work by the Roth firm. Director Hübel, as a representative of ‘Textilana’, gave his consent for the floorboards to be repaired. The carpenter was suggested to use the decking from the first-floor ceiling for dividing off the ground-level hall into a booth (all of this work was carried out without the knowledge of the Building Police).

Director Hübel moved the Building Police inspection of the factory to Monday, 4 December in order to arrange for safety measures. The following gentlemen undertook the inspection (on Tuesday, 5 December): Municipal Councilor Ullrich, Construction Director Ing. Grünwald, the police office, a representative of ‘Textilana’, a representative of the police station in Rochlice, Mr Kratochwil from the DAF and the Roth firm.

It was ascertained that this building is very unstable, its windowpanes have been smashed, and for basic repairs the amount of 1 200 Reichsmarks will be necessary. The oil stoves are sunk into the floor and the flu is insufficiently constructed of metal and leads out through an open window. The Building Police also said the roof of the factory is in very bad shape, the window posts on the south-facing side are in danger of collapsing, and the brickwork is crumbling. The flue leading to the first floor is ruined. The false ceiling on the first floor is partially destroyed and could easily fall through to the ground floor. It was determined that the entrance to the hall should be promptly closed and the doors leading from the chamber to the hall must be locked. In the event of a storm, there is a danger of part of the roof flying off, and the windows, which cover a large area, could break off and fall not just on the residents of the factory building, but also on the neighbors. Primarily, however, the question of heating must be resolved.

For the most necessary repairs 1 200 Reichsmarks are necessary. However, that is only on the assumption that accommodation in this dilapidated building will just be temporary. Such investment would be wasteful at this time, when building materials are being frequently released for new constructions. Director Hübel and the representative of the Building Police, therefore, reject this form of accommodating the Gypsies and will not take any responsibility for it.

The head of the police station at Rochlice then pointed out to the members of the commission that there is an abandoned gym near the Votoček place in Horní Růžodol, no. 196, and noted that there was no reason the Gypsies could not be accommodated there. On the basis of that suggestion, the gym was inspected and it was found that there were no circumstances against accommodating the Gypsies there. The manager of that property, Mr Seibt of Horní Růžodol 138, pointed out that the parquet flooring of the hall could be put to a more appropriate use. The local head of the NSDAP [the Nazi Party] might also raise objections.

4 December 1939“

This report clarifies what the conditions in Liberec were in relation to Romani people in the year 1939. The Roth firm was exploiting Romani labor in its construction projects, and in relation to all of the other entities, it bore responsibility for the laborers.

Kratochwil of the DAF, understandably, was also on the side of the Roth firm. Romani people were working for Roth on the construction of the housing estate called “Heimstätte – Domov” (Homestead), which today is located in Liberec V in the Králův Háj neighborhood.

The housing estate is comprised of 15 buildings, numbers 325-330 and 332-340, all connected into eight tower blocs. The builder and investor into the construction was the Company for the Construction of Residential Buildings and Housing Estates in the Sudetenland, and the manager was the Domov Sudety (“Homestead Sudetenland”) company, which later supervised the construction.

The Roth firm de facto carried out the construction according to a project designed in 1937. Construction began after May 1939 and the final details, such as the fencing, etc., were completed in 1941.

The other side of this dispute over where to accommodate the Romani forced laborers is comprised of the representatives of the town and the owner of the building at number 120, who essentially did not wish to use the building as a camp and, as the report states, washed their hands of responsibility for the accommodation (despite the fact that they also offered no small amount of money and human resources for repairing the building). What is interesting is the final paragraph of the report, with its mention of a public house (“the Votoček place”) and a gym, U Votočků, because later a Russian prisoner-of-war camp was established there.

Unfortunately, it is not stated why the local leadership of the Nazi Party might have objected to that use of the gym. It is possible that some type of labor camp was already being planned at that time.

The question remains as to where the Romani families actually were accommodated during the building of the housing estate that is located today in Králův Háj. They could have been accommodated in two wooden barracks built in 1939 on the campus of the quarry near Kunratická Street.

According to the cadastral map and the land registry, wooden barracks were built there sometime around July 1939. It is possible that precisely those buildings are the ones mentioned by Romani Holocaust survivor Růženka B. in her testimony about the position of the Romani camp near the quarry – they better correspond to that description than does the camp for Romani people built later below the existing quarry, which will be described in more detail in the final part of this series.

Roma were put up with as a labor force

During the months that followed this communication, what was addressed was primarily the state of the building and its occupation. There were three parties communicating about the problem.

One party was the firm exploiting the Romani labor together with the state apparatus that was later in charge of their murder, the second party was the City of Liberec as an intermediary, and lastly there was the Textilana joint-stock company, which owned the building. Despite the fact that the problem of accommodating the Romani workers grew into a dispute, none of the parties involved was ever interested in improving the living conditions of the Romani people interned at the camp.

The only reason the presence of the Romani families was suffered was that they constituted a labor force. They were moved into the camp on 1 December 1939.

In a letter dated 28 December 1939 addressed to the Textilana company, Mayor Rohn summarizes the conditions of the accommodation. The city promised to lease the big ground-floor hall for the purpose of accommodating the Roma as of 1 December 1939, with room for 80 persons, as well as a room and other spaces on the first floor of the factory building.

The Roma were to be accommodated there until 31 March 1940, i.e., a mere four months. On 18 December 1939 the building was inspected again, and this time the delegation was joined by an Inspector Schwarz from the Criminal Police, as is mentioned in eyewitness testimonies.

At the same time, reconstruction of the space was carried out, consisting of installing new stoves that ran on coke and partially repairing the big factory hall. The work of repairing the building was completed on 27 December 1940.

During the entire time that the camp for Romani people existed on Nádražní Street, only two complaints were ever recorded about the living conditions there. The first complaint was raised in January by a Mr Funke, who called the conditions in which the Romani laborers were being accommodated undignified and inhumane and demanded that Mayor of Liberec Rohn and local mayor Schmuck personally inspect the spaces.

A question was also raised with Konrad Henlein, Reichsstatthalter of the Sudetenland in 1939, regarding the matter of the future plans for the Romani families. If there was an answer made to that inquiry, it has not been preserved.

Director of Textilana writes to the mayor

On 27 March 1940, four days before the Romani laborers’ tenancy was to expire, the director of Textilana sent the mayor a letter saying he hoped they would leave soon. He also demanded the building be cleaned, as it was in a forlorn state.

His supporting arguments for evicting the Roma were that the local well had been polluted and that neighbors of the camp had complained. Such a letter was not long without a response – and mainly it had to be explained.

On 5 April 1940, five days after the Romani laborers’ tenancy had expired, a letter was sent to the Textilana company. It is not clear who wrote it, but the text indicates that it was from the initiator of the establishment of the camp on Nádražní Street, perhaps even Kratochwil of the DAF, and it reads:

“In October of last year you entrusted me with accommodating the Gypsies now present in the Liberec area. At the same time, you noted that the detention of the Gypsies was just temporary and that there was a plan to establish a concentration camp near Liberec. I then met with the director of ‘Textilana a.s.’ in Chrastav, Franz Hiebel, and we agreed that all the Gypsies could be accommodated in the abandoned factory building no. 120 in Rochlice on Polní Street. That agreement expired as of 31 March 1940 and ‘Textilana a.s.’ is urgently demanding the building be cleared out.”

This is the first and also the last time that the concept of a “concentration camp” turns up in these documents – in this case, moreover, from a person who was probably well-oriented in this particular issue. There is also no need to speculate in this specific case about the specific official meaning of the term “concentration camp”.

The conditions in the facility were shocking, as is documented by a complaint filed by Romani laborer Franz Bernhard with the police station in Rochlice. In his complaint, Bernhard describes the catastrophic state of the building.

The factory is described as collapsing of its own accord, and so loudly that those accommodated there could not sleep and their lives were in danger. On the basis of that complaint, the commission inspected the building and arrived at a very paradoxical conclusion.

While the factory was so absolutely dilapidated that even the masonry was destroyed, it was said to pose a danger only to the neighboring buildings, not to the Romani people accommodated inside it. At the same time, the commission acknowledged that the bricks and plaster falling from the walls were actually causing loud noises.

Nobody was interested in investing into the dilapidated factory, and the report also demonstrates the strongly negative relationship between the authorities and the Romani laborers interned in the camp. In the interim, the Textilana company was continually demanding the building be cleared out, so Mayor Rohn turned to Henlein, and to the Governing President in Ústí nad Labem, Hans Krebs, and to the local police president in the matter, but we do not know whether he ever received an answer from any of them.

In November 1940, the factory chimney had to be demolished, as it was in danger of collapse. In June 1942, correspondence references demolishing the building, and on 16 June, Mayor Rohn thanks the Textilana a.s. company for having provided the building for use.

Sometime between June and August, the camp for the Romani prisoners on Nádražní Street was closed and they were moved into a newly-built camp near Kunratická Street, where they were accommodated until they were transported to the concentration camps of Auschwitz, Buchenwald and Ravensbrück. Building no. 120 then underwent reconstruction.

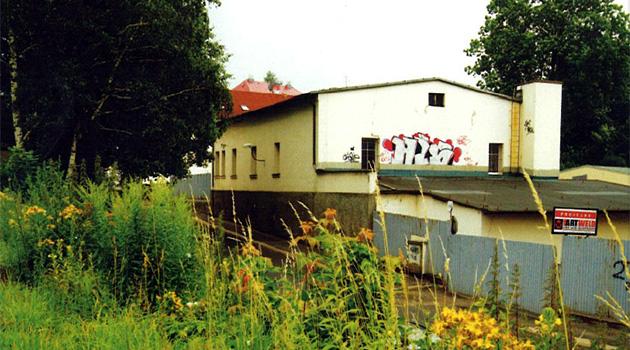

An entire floor was taken down and the factory became a potato cellar. After the war it was a vegetable canning plant and later a Mototechna plant, and it stands there to this day in a significantly altered state.

We thank the author for his kind permission to publish these excerpts of his texts.