Stano Daniel: Czecho-Slovak perspectives on elections to the European Parliament

“I won’t be voting. Do you know how much those MEPs get paid?” a lady on the third floor responded after a politically active neighbor from the 11th floor gave her an EP election flier for a Romani candidate.

The reaction wasn’t racism. It wasn’t even logical.

She may have been motivated by envy, or perhaps a lack of interest. She was certainly ignorant.

The lady in this story, which happened in Bratislava, Slovakia, in 2014, was responding like most of the population there did. Just 13.05 % of eligible voters participated in the EP elections there last time.

Citizens of the Czech Republic secured the second-lowest turnout for themselves in the 2014 EP elections, at 18.2 %. Both countries sent a clear signal of no interest in who would represent them at the EP.

Too distant from the people

One of the most frequent reasons given for low turnout in the EP elections is the social distance of those elected from ordinary people – geography itself is a second-order concern here. The much greater challenge for the EP is the fact that few people understand it.

This especially applies to the Romani men and women living in social exclusion throughout Europe. The areas in which EP lawmakers exercise their powers are also significantly distorted by the populist online portals that write about issues such as the curvature of bananas and cucumbers and EU regulation.

The populists who wage political battle against the “European Commission’s dictatorship” do not contribute to increasing public comprehension of EU institutions either. It is not surprising, therefore, that the average person would be confused about the EP elections under these circumstances.

What, then, is the EP for? We can aid our understanding by taking the example of the EU budget – the one that provides financing for highway construction, scientific research, mortuaries, projects in the schools, technological innovation, expanding job opportunities, improving the accessibility of health care, and many other matters.

The EU budget is proposed by the European Commission, but it must be approved both by the Council of the EU (which is comprised of Member State representatives – presidents or prime ministers) and by the European Parliament. Both the Council of the EU and the EP are directly-elected representatives, a fact that could easily destroy the notion of this legendary “Brussels dictatorship” – if more people would just take an interest.

Risks (and maybe, advantages) of tragically low turnout

The fact that most of us do not take an interest in these elections, especially when it comes to disadvantaged groups in the population such as Roma, can be an advantage for some stakeholders. Lower turnout creates room for different extremes to occupy the space.

If a candidate managed to organize Romani voters in Slovakia, their increased participation during an otherwise dismal turnout could redraw the election outcome in a fundamental way. However, this also applies to other extremes, especially the political ones.

The Fascists, who are already so well-organized, could easily abuse this situation. Marian Kotleba, the chair of a party that includes his name in its own because of his popularity, got slightly more than 220 000 votes in the recent presidential elections in Slovakia.

In 2014, the total number of ballots cast during the EP elections – for all candidates of all parties – was just 560 000. In 2019, all that is sparing us the blight of extremism is essentially the lack of interest or the laziness of our centrist voters.

Constantly proving something

Just as in 2014, several Romani candidates will run in the upcoming EP election and seek support in Slovakia on the candidate lists of both bigger and smaller parties. Once again, voices are heard asking: Why don’t they unite and run as a single Romani party?

The problem here lies elsewhere, because historically none of the Romani representatives seated in the EP have ever been elected from the candidate list of a Romani party. The few who made it to Brussels/Strasbourg were voted for by non-Romani voters above all.

Of all these candidates, MEP Soraya Post is the brightest star, who was elected primarily as a feminist, although she proudly espouses her Romani identity as well. That could be a recipe for other Romani candidates.

Appealing “too much” to Romani voters can be risky, as the author of this piece has experienced. In 2014, I myself ran for the EP, albeit unsuccessfully.

One example can represent my entire experience: In one southern Romani community, I received 11 votes. That was the total number of all the ballots cast in that community.

The problem back then was not so much convincing Romani people that a candidate had the qualities necessary to represent them, but rather convincing them about the importance of these elections in the first place. Simply put, we Romani candidates must offer something more.

Romani candidates may have to offer more than a non-Romani candidate does. Elections are not free from discrimination – including by Romani voters.

All that aside, we Roma need to attempt being elected. If it means we have to be twice as good as anybody else, then we will be!

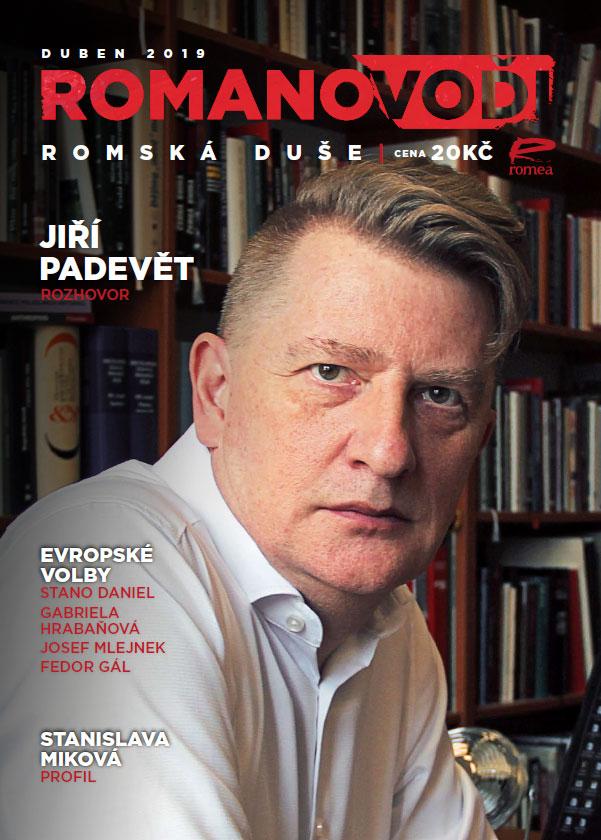

First published in a special issue of Romano voďi magazine focused on the elections to the European Parliament. The special issue was published with support from the German foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future” (EVZ).