Romani people have faced discrimination and exclusion since Czechoslovakia first became a state

The Czech Republic has just commemorated its 103rd anniversary of the creation of the independent Czechoslovak Republic in 1918. Events were held to mark the anniversary country-wide.

What was it like for Romani men and women during what is now called the First Czechoslovak Republic? The democratic constitution officially recognized many national minorities, but not Romani people.

The period immediately following the birth of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918 did not yield any essential change for Romani people initially. The Austro-Hungarian legal norms still in effect in the new country continued to apply to them.

The most significant of those laws was a decree promulgated by the Interior Ministry in Vienna on 14 September 1888 that brought all of the existing anti-Romani measures into one and the same ordinance. Those measures involved deporting Romani foreign nationals and defined the punishment for and coercion of Romani people living on the road.

That law also legislated the issuing of documents for Romani citizens. In Hungary, such a law was not adopted until 1916, and it took a milder form.

From the beginning of the 1890s, petitions began to appear from rural villages throughout Czechoslovakia calling for the adopton of a law that would further limit the movements of Romani people. The consequence was not just the performance of a head count of Romani people in 1925 (a total of 64 938 people counted, 62 192 in Slovakia, 1 994 in Moravia, 579 in Bohemia and 79 in Silesia), the results of which probably underestimated the actual state of affairs (according to estimates, there were between 70 000 and 100 000 Romani people living in Czechoslovakia at that time), but also the adoption of Act No. 117/27 Coll., “on wandering Gypsies”, dated 15 July 1927, was the main outcome of those petitions.

The template for that law was French legislation on travelling people from the year 1912 and a Bavarian law “on gypsies and idlers” from 1926. The Czechoslovak treatment of what was called the “Gypsy Question” was among the most thoroughgoing in the world and was used as a model in the 1930s at international criminological conferences.

The initiator of the acceptance of the law was the Agrarian Party, mainly. On its basis, during 1928-1929, a head count of “wandering Gypsies” was performed, on the basis of which the “Headquarters for the Registration of Wandering Gypsies” issued all of the persons registered by that head count “Gypsy identity cards”.

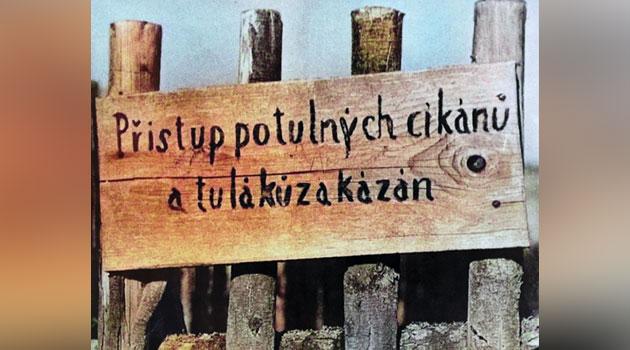

In Czechoslovakia, until 1938, about 36 00 such pieces of identification were issued. The implementing regulation for that law established places where those holding such identification were forbidden from entering (especially in Prague, Brno, and some spa towns).

The law and the forced head count arising from it affected the Bohemian (Czech), German (Sinti), and Vlax Romani groups in particular. The head count recorded members of those groups above all, for whom it was natural at that time, in association with their traditional way of making a living, that they led a semi-itinerant life or lived on the road.

The wording of the law as well as the implementation of the regulations in practice evoked a certain critique at the time. “Ladies and gentlemen! The law on gypsies that lies before us is not just an exceptional piece of legislation, it is also unconstitutional. […] According to this law, all gypsies, almost without exception, will be stigmatized as chicken thieves. The rapporteur, Mr Viškovský, has declared that this law had to be written because all gypsies – he was generalizaing – refuse to work, avoid it and are lazy,” said Irene Kirpalová of the German Social Democratic Workers’ Party in the Czechoslovak Republic during the debate on the law.

From today’s perspective, the law is unequivocally discriminatory. It is also essential to realize that through this legislation, inhabitants who were not Romani but who somehow displayed the signs of persons living the “Gypsy way of life” were also included in the head count and registry.

On the other hand, many Romani people did not live “like Gypsies” from the perspective of this legislation. During the First Republic, in continuity with preceding historical developments, most of the Romani population in Moravia and Slovakia in particular lived settled lives.

The settled Hungarian and Slovak Romani people applied themselves in society as artisans who worked on a small scale and were sought after, especially as blacksmiths, horseshoers, producers of mud bricks, baskets and brooms, products made from corn husks, etc. It remains a fact of history that Romani people did not own, nor did they manage, any larger plots of land, but made do with their own small plots on which they resided.

On the other hand, the First Republic was a time when several Romani people graduated from both high school and university education. Tomáš Holomek of Svatobořice successfully completed his studies at Charles University’s Faculty of Law in Prague in 1936.

In 1926, the first school for Romani children was established in Uzhhorod (today Ukraine) and was built by Romani people themselves. In the 1930s, a music school for Romani people was established in Košice, Slovakia.

Questions associated with the life of Romani people also began to be studied by several Czech scholars (the Indologist V. Lesný and the pedagogue F. Štampach). Despite the discriminatory law about “wandering Gypsies” and other lawful measures, the gradual integration of Romani people into society was clear and had already begun during the 19th century.

Sources:

Steklá R., Houdek L., Druhá směna, ROMEA, 2012

Petr Lhotka, skola.romea.cz

Nečas C., Romové v České republice včera a dnes, Olomouc 1995

Nečas C., Nad osudem českých a slovenských Cikánů 1939-1945, Brno 1981

Šípek Z., Řešení situace potulných Cikánů v českých zemích v letech 1918-1940. Neznámý holocaust, Praha 1995

Thurner E., Zigeunerefeindliche Massnahmen in der Zwischenkriegszeit, Praha 1995