Czechoslovakia's 1989 Velvet Revolution: 800 000 people in Prague chanted "Long live the Roma"

On 17 November 1989, the totalitarian regime of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic began to collapse. How were Romani people involved in what would be called the Velvet Revolution? Did you know that on 25 November 1989, 800 000 peple were chanting “Long live the Roma” on the Letná Plain in Prague?

The bulk of this article was first published by Romea.cz in Czech in 2014. It has been updated this year to include information from Emil Ščuka’s book I Am the Gypsy Baron (Cikánský baron jsem já).

Dissidents who were Romani and the “gray zone”

As far as the Czech part of the Czechoslovaki dissident scene is concerned, the Romani minority was probably represented there by just one person, Karel Holomek, who signed on when the Movement for Civic Freedom (Hnutí za občanskou svobodu – HOS) was established in 1988. After the 1968 invasion by the Warsaw Pact troops and the beginning of the “normalization” era, Holomek was expelled in 1981 from military college as well as from the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), arrested, and interrogated on suspicion of “subverting the republic” – his summer house became a rendezvous point for the dissidents Ivan Klíma, Jiří Gruša, Jan Trefulka, Ludvík Vaculík, Eda Kriseová, Milan Šimečka or Miroslav Kusý.

In April 1986, according to Petr Víšek, a group of Romani men (Baláž, Gergel, Oláh) wrote a letter to the Central Committee of the KSČ with a request that the problems being experienced by Romani people be solved. The group then created, in 1987, the preparatory committee for a future Romani Union in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (Svaz Romů v ČSSR). In June 1988, Tibor Baláž and Vlado Oláh met with the Central Committee of the KSČ and the leadership sharply informed them that while “the establishment of an ethnically-conceived social organization would be quite a problematic step with a dubious outcome,” the continuation of “dialogue that is directed by us, not forced on us from the outside by self-appointed spokesmen for the ethnic Roma, is something that we do currently consider expedient”. The next such meeting, according to Víšek, was held on 4 November 1988 at Hotel Praha. Romani representatives in attendance were ing. Holomek, E. Baláž, M. Demeter, V. Oláh, E. Ščuka and others, about 20 people altogether. They were received by Secretary Hoffman of the Central Committee. On 14 January 1989, a formal meeting that reached no conclusions was also held.

The Roma Civic Initiative (ROI) at a time of black and white brotherhood

After the events of 17 November 1989, activists who were Romani assembled on Monday 20 November and agreed to gather every evening to discuss what was happening. On Tuesday, 21 November, a crucial meeting was held in the apartment of Ladislav Rusenko, the manager of the Perumos folk dance ensemble. Those attending were Emil Ščuka, Agnesa Horváthová, Zdeněk Cvoreň, Vlado Oláh, ally Milena Hübschmannová and others, most of them Romani residents of Prague’s Žižkov quarter, according to Ščuka’s book.

That meeting resulted in a petition by the Roma Civic Initiative (Romská občanská iniciativa – ROI) through which the Roma joined the Civic Forum (Občanské fórum – OF) declaration. Also on 21 November, ROI released two statements of their own to be disseminated in Romanes and Slovak by the rebelling students, the OF and by Romani people themselves. The statements took the form of fliers that were copied at the Charles University Faculty of Pedagogy mainly thanks to Kateřina Sidonová, daughter of the Charter 77 signatory who would later become the Chief Rabbi of the Czech Republic, Karol Sidon. The texts of the statements were drafted by ally Hübschmannová and Romani community members Rusenko and Ščuka and were drafted in an apartment in Prague used by Rusenko and Žiga.

One of the Czech-language fliers exclaimed:

“Sisters, brothers, Roma, let’s wake each other up! The day has arrived that our predecessors spent many long years anticipating. That day is here. The Romani people who live in this country are able, for the first time ever, to take their fates into their own hands. Now it is up to us to agree on how to stick together and what we will do for our children. Let’s come together with the people who are willing to listen to us. That is the Civic Forum (OF). The OF has recognized our party, the ROI. OF and ROI stand by all of the Romani people in this country. Let’s lift up our Romanihood for a better life. Let’s not forget the truth our fathers told us: Show respect and it shall be shown to you: Emil Ščuka, Jan Rusenko – Roma Civic Initiative.”

Another piece, called the Declaration, mobilized the public in the Slovak language:

“We, the Civic Initiative Committee, which represents 800,000 Roma citizens living in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, have adopted the following opinion:

1) We Roma, who have a thousand-year history of sorrow and suffering, persecution and humiliation, condemn the inhuman intervention by the forces of order of this state against the defenseless people who worship the memory of Jan Opletal.

2) We unequivocally support the statements of the university students, the artistic public, and the Czechoslovak Committee for Human Rights and Humanitarian Cooperation and we agree with their demands.

3) The Roma Civic Initiative identifies with and supports all of the demands expressed by Civic Forum on 20 November 1989.

4) Through this opinion, which expresses the opinion of the vast majority of Czechoslovak Roma, we hope that the beginning of this social change will yield an actual democracy in our country.

Prague, November 21, 1989

Roma Civic Initiative Committee.”

The students later publicly thanked the Romani people in an emotional, florid style:

“We thank you all for supporting us students and all who have been persecuted for so many years. You yourselves all know best what it is like to be persecuted, humiliated and oppressed. People who have open hearts and open eyes have seen 20 years of injustice and a murderous stupidity all around them here. People have lived in fear and powerlessness, afraid to take a direct path to their destination. It seemed that humanity itself had lost its value. A useless anger darkened the minds of many people, and in this quandary they have been taking their anger out on those who ‘never picked up an axe in their lives’ – the Roma. However, now a way has opened up for all of us to achieve what is good, to have lives, to be human. Let’s walk down this road together. Let’s get to know each other, let’s create a society, hand in hand, where a person will have the opportunity to learn what decency is, where black people and white people will be respected, and where each person will be able to become a human being. We cannot walk this human path through violence and with the Devil, but with the Good Word, with mutual understanding and with love in our hearts. We may not walk quickly, but if we stick to it, we will get there. University students, 25 November 1989, Prague.”

The ROI condemned the KSČ for the way it had addressed the issues of the Romani population and demanded that Romani nationality be anchored in the new Constitution. Rusenko and Ščuka brought their Declaration, signed on behalf of the ROI by 13 people, to the headquarters of OF at the Laterna Magika theater, where they were received by Václav Havel and others.

“Friends, the Roma are joining us! Here is their declaration, the declaration of the Roma Civic Initiative! Welcome, come be with us. The door is open to you here,” Ščuka describes Havel’s reaction at the time.

On 24 November 1989, Ščuka became a member of the Concept Committee of the OF, and together with Rusenko was given an opportunity to make a televised appearance before almost the entire nation.

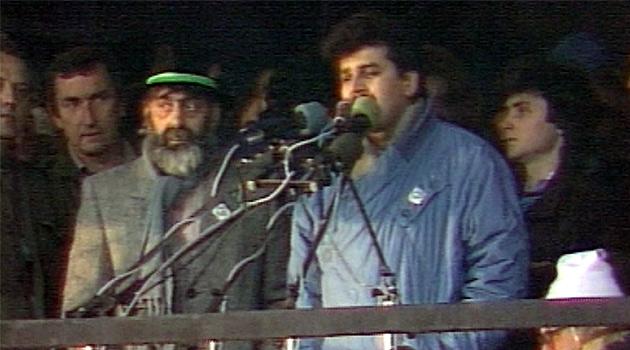

On 25 November Rusenko and Ščuka, together with the top leaders of the opposition, spoke to a crowd of hundreds of thousands on the Letná Plain in Prague that reached most households in Czechoslovakia through television. A group of Romani people unfurled a Romani flag at the same time and the mighty crowd chanted “Long live the Roma”.

On 9 December 1989 several Romani figures met in Prague to form a more narrowly-defined preparatory committee for the ROI. They included Jan Rusenko, Emil Ščuka and Vojtěch Žiga, and the ROI became a component of the coordination center for the OF.

The miracle of 1990-1992: Eleven Romani legislators

After 17 November 1989, under pressure from the opposition, 64 members of the Czech National Council (Česká národní rada – ČNR) resigned and their seats in that legislature were co-opted by adherents of OF. The democratic opposition called on the ROI to propose their own representative to the ČNR. ROI nominated Karel Holomek. As a representative of the ROI, Holomek made history when he was appointed to the OF candidate list on 6 February 1990. He later became the first Romani lawmaker elected in a democratic Czechoslovakia. As it happens, his father Tomáš Holomek, an army officer, was the first-ever legislator from the Romani community during communism at the beginning of the 1970s.

The constitutional convention of the ROI took place on 10 March 1990 in the Eden House of Culture in Prague. There were 438 delegates who elected a Central Committee (Ústřední výbor -ÚV) comprised of 30 Romani people from the Czech lands and 22 from Slovakia. The ÚV then elected Ščuka to lead the party. The ROI, from the time of its convention, was also counted among the members of the International Romani Union (IRU). The ROI program declaration stated:

“The ROI is an open, supra-ideological political party bringing together all citizens irrespective of nationality and religion who are concerned about the fate of the Romani people. The ROI plans, through its own specific tools, to contribute to creating genuine equality, elevating the level of the Romani nationality as a whole in terms of their living standards, culture, and political and social participation. It will strive to see the Romani nationality recognized. The ROI will uphold the right to work, the right to social security and to security in case of old age, illness, disability and difficult life situations. It will strive to see that incorrect ways of addressing housing provision for Romani people are not pursued as they have been sometimes in the past, i.e., when such people were concentrated in ‘housing estates for Roma’ that have become certain ghettos in their absolute isolation and segregation without taking into account the currently significant different lifestyle of Romani families. The Roma do not want to be segregated away from the education system for the rest of the population, they do not want to establish their own, separate schools. The cultural and ethnic specificity of Romani people should be respected at all levels of the school system.”

Ščuka also began to engage with the IRU. When the Fourth World Romani Congress of the IRU assembled from 8-11 April 1990 in Serock near Warsaw, Poland under these changed conditions, 250 representatives from 24 countries attended. Most of those participating were from Eastern Europe – Rajko Djurič of Yugoslavia became the IRU president and Ščuka of Czechoslovakia became its general secretary.

In the beginning of the transition to a democratic Czechoslovakia, practically all of the eminent figures of the Romani world assembled in the ROI and were engaged with it, suppressing their personal disputes, animosities between different families, and differences of opinion for the time being. When the first free elections were held in June 1990, the Romani representatives in the Czech lands ran under the wings of the OF, while in Slovakia they were part of the Public against Violence (Veřejnosti proti násilí – VPN). That led to their securing eight seats for the ROI. Those seated in the Federal Assembly (Federální shromáždění- FS) were the Czech pro-Roma activist Klára Samková for Prague, while the Czech National Council (ČNR) seated Dezider Balog for the West Bohemian Region, Zdeněk Guži for the East Bohemian Region, Ondřej Giňa for the Central Bohemian Region, Karel Holomek for the South Moravian Region, and Milan Tatár for the North Bohemian Region. Romani lawmaker Ladislav Body was elected on the Communist Party list, having been a member since 1979.

The ROI in Slovakia, running as part of VPN, seated Gejza Adam in the FS and Anna Koptová in the Slovak National Council (Slovenská národní rada – SNR). In addition, two Romani candidates from Slovakia, Vincent Danihel and Karol Seman, were seated in the FS for the postcommunist Democratic Left Party (Strana demokratické levice – SDL). These results were the best for political representation by Romani people that has ever been achieved in Czechoslovakia or its successor states – they were a component of a coalition government that was still able to take advantage of the euphoria of the transition and the hope of the minority whom the government wanted to represent.

Once elected to the ČNR, Body, Giňa and Holomek became members of the Committee for Territorial Administration and Nationalities, Tatár became a member of the Constitutional Law Committee as well as a member of its presidency, Balog became a member of the National Economic Committee and Guži became a member of the Committee for Social Policy and Health Care.

At the beginning of the 1990s, the ROI officially had 60 000 members, but most probably in actuality were loosely affiliated with the party, as was the case with several other parties during the post-1989 period, e.g., just as petition signatories supporting the initial registration of the group.

When local elections were held in November 1990, the ROI ran as an independent party in both parts of the country. In the Czech lands they won a total of three local mandates with 0.11 % of the vote.

For Mečiar in Slovakia, for Klaus in Czechia

The growing Czech-Slovak tensions gradually built up a barrier within the Romani party as a statewide entity. “The Central Committee of the ROI Slovak Congress asks you to not participate in Brno. Doctor Gejza Adam, Košice” – this was the wording of a telegram sent to the Slovak delegates to the ROI’s statewide congress planned for 25 January 1991 in Brno. However, some of the ROI delegates from Slovakia did attend and informed the ROI leadership of Adam’s rebellion against them. The 200 attendees of the statewide ROI then re-elected Ščuka their chair.

When the tendencies to divide Czechoslovakia into two separate countries gained strength, the Federal Council of the ROI responded in May 1991 with a declaration demanding the federation be preserved. Adam’s rebellion and the different directions of the Czech ROI and some of the Slovak ROI was explained by Ščuka in his book as follows:

“In the new year we were divided by the group around MP Dr. Adam. He was of the opinion that Slovakia would become an independent country and thus there was no need for a federal party, and that the only politician who sincerely meant everybody well was Mr Mečiar. We were of the opinion that anybody could put together a likable social policy, but the only party that would stand the test of time would be the one that finally begins to tell people the truth, not some Mečiar, not some Civic Movement (Občanské hnutí). Can anybody even tell me what that is? I think that only Klaus is unafraid and has the strength to tell it like it is.”

In addition to the ROI, dozens of cultural organizations, interest groups and political organizations gradually appeared on the scene in almost all of the areas where members of the Romani minority lived in Czechoslovakia. Instead of the anticipated unification of Romani people, the movement fell apart due to disputes between extended families and individual leaders. By 1992, the ROI was just 300 actually dues-paying members, although on occasion it still referenced the number of 60 000 members from the period right after 1989. The swinging of the political pendulum in the Czech lands to the right also influenced the head of the ROI and his subordinates, as can be seen from this ROI text of the time:

“In the Czech Republic we have 20 000 members in 200 local organizations, in Slovakia we have about 30 000 members in 180 organizations. We are doing our best to explain the essence of the economic reforms to our members. Not everybody comprehends them, they are saying things were better under the communists, that there was money and we didn’t have to do anything. We are now in a time of transition, it will not happen without problems, but the reform has a schedule in time and if it succeeds, ultimately everybody will be better off. I have held a meeting with the chairs of all the district organizations and today I can say that 90 % of them favor the right-wing direction. We reject the left, which has caused this country to be devastated economically and morally.”

The post-revolutionary transitional time came to an end, and the head of the strongest-ever formation of Romani representatives did his best to incline members of the Romani minority toward becoming adherents of free markets “plain and simple”. His successor as head of the ROI, however, managed to make an even bigger move to the right several years later.

This summary is based on a thesis by Jakub Krčík, Romské politické hnutí v České republice v letech 1989 – 1992 (Praha, 2002) [Romani Political Movements in the Czech Republic 1989-1992 (Prague, 2002)] and Pavel Pečínka’s publication Romské strany a politici v Evropě (Brno, 2009) [Romani Parties and Politicians in Europe (Brno 2009)].

First published by news server Romea.cz in 2014, updated by Zdeněk Ryšavý in 2021.