How the Czech compensation mechanism for illegal sterilizations is (not) working so far

The victims of illegal sterilizations performed on the territory of what is today the Czech Republic between 1966 and 2022 have been able to apply for one-time compensation in the amount of CZK 300,000 [EUR 12,000] since the beginning of the year. However, in practice this compensation mechanism has its limits and civil society has been consistently warning of its dangers.

Illegal sterilizations on Czech territory began before the turn of the millenium, but we also have documented cases from this millenium. Attention was drawn to this practice in 2005 by the then-Czech Public Defender of Rights, Otakar Motejl, who was also the first to begin to speak about opportunities to compensate these victims.

Many years of struggle followed by NGOs and the victims themselves until, on 1 January 2022, the law took effect that awards this one-time amount of CZK 300,000 [EUR 12,000] to the victims of these illegal sterilizations. The Human Rights League, where the author of this commentary works, has been aiding the victims of illegal sterilizations with applying for compensation.

When the law was written, it counted on approximately 400 women eventually being compensated. Their applications were first to be assessed by a commission comprised of experts who have long studied the subject of illegal sterilizations and who would be able to contextualize them as a human rights issue.

The decisions to award compensation were meant to be issued on the basis of such assessments. This decision-making eventually fell onto the agenda of the Czech Health Ministry, which decided not to establish such a commission.

Romea.cz first republished this article in Czech with the consent of the author and the editors of news server Pravo21.cz – where it was originally published as Protiprávní sterilizace: Jak (ne)funguje odškodňovací mechanismus?

For the time being, roughly half of the applications have been successful, and so far the only evidence being recognized by the ministry are the original medical records of these procedures. This is despite the fact that the explanatory report on the legislation states that other kinds of evidence to be considered could, for instance, be sworn statements from the applicant or others with knowledge of these events.

Context in history

In Europe, sterilizations of a eugenic nature were perpetrated during the 20th century, for example, in Czechoslovakia, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland. The reason was to “improve the population”, and the target of these illegal sterilizations were chiefly women who had been labeled as mentally disabled and women from socially vulnerable conditions.

In Czechoslovakia, forced sterilizations affected Romani women most frequently, but some non-Romani people were also subjected to this treatment. This policy was supported by the state and undertaken in public medical facilities.

Naturally it is not possible to say that any and all sterilizations performed during communism in Czechoslovakia were human rights violations. Some people did genuinely request them and were sufficiently informed about this surgery, its risks, and its irreversibility.

While the stories of the forced sterilizations do vary somewhat, they are nevertheless similar to each other. What are frequently repeated are descriptions of pressure and threats from the state that the women’s already-existing children would be taken away from them if they were to conceive again and that their agreeing to undergo sterilization would therefore spare them such a fate.

Other accounts describe women in labor awaiting delivery by Caesarean section who are asked by medical personnel to sign blank pieces of paper (or are even asked to do this a couple of days after delivering their child). Others report that their doctors told them sterilization was the same as temporary birth control.

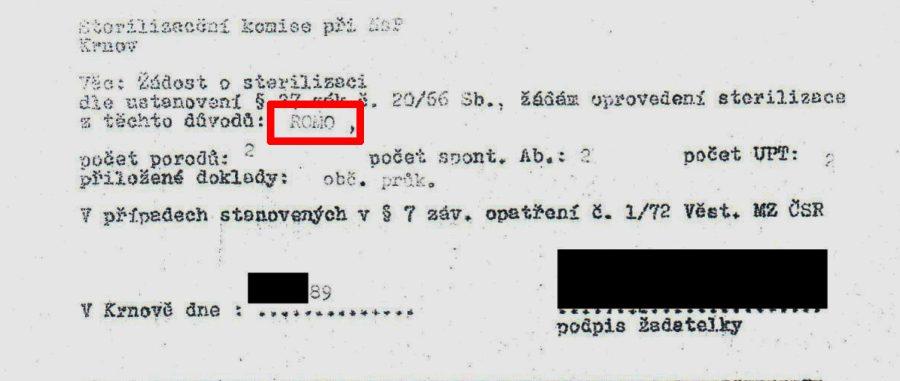

One-time social benefits were offered to women to undergo these procedures (frequently without explaining their irreversibility). Officially, Act No. 20/1966 Coll., “on care for the health of the people”, conditioned sterilizations on the provision of informed consent and required them to follow the approach established by directive no. LP-252.3-19.11.71., on the performance of sterilization (hereinafter “the directive), but these regulations were systematically violated in practice.

European Court of Human Rights case law on these human rights violations

Several cases of forced sterilizations have been reviewed by the European Court of Human Rights (hereinafter the ECtHR). The most famous case is that of V. C. versus Slovakia, from which the Human Rights League has drawn its legal arguments for the compensation requests in the Czech Republic.

In that case, the ECtHR found that Article 3 (the prohibition on torture) and Article 8 (the right to respect for one’s private and family life) of the European Convention on Human Rights had been violated. The court, with respect to the violation of Article 3, assessed above all whether consent to the surgery was informed, as well as the circumstances under which it was performed.

From that assessment (e.g., the applicant was asked to consent to surgery while in labor and in pain, just before delivery, in a state of fear caused by her doctors’ communications with her and without enough information about the surgery being provided to her), the court assessed the approach of the health care personnel as incompatible with the principle of respecting human dignity and freedom. Moreover, her physical integrity was grossly violated.

With regard to the violation of Article 8, the ECtHR found that the state’s positive obligation to guarantee respect for one’s private and family life had been violated. This particular woman lost her opportunity, at a young age, to conceive more children, without ever freely deciding to do so.

The ECtHR has not found violations of both Article 3 and Article 8 in all of the cases of forced sterilization which it has reviewed, however. In a recent decision, Y. P. vs. Russia, the court ruled that only Article 8 had been violated.

In that case, according to a majority decision, there was no racial discrimination involved (Y. P. is not a minority member), the gravity of the violation did not rise to the level of an Article 3 violation and the element of vulnerability was absent. Justices Serghides and Pavli, on the other hand, wrote a dissent advocating for the opinion that Article 3 was violated in this case (they argued, for example, that any pregnant woman undergoing an operation is inherently vulnerable).

Czech(oslovak) legal conditions and the approach to sterilization before 2012

As I have already mentioned, under certain circumstances, sterilization can be performed lawfully. According to section 27 of the law on “care for the health of the people”, it was possible to perform sterilizations only with the consent of the person concerned or at that person’s request, and then only under the conditions established by the Health Care Ministry in its directive.

Romea.cz first republished this article in Czech with the consent of the author and the editors of news server Pravo21.cz – where it was originally published as Protiprávní sterilizace: Jak (ne)funguje odškodňovací mechanismus?

Consent to the sterilization had to be free, informed, and in writing. In the case of sterilizations being performed on sexual organs that were healthy (a list of medical indications for the performance of sterilization was established by an appendix to the directive), the approach was meant to be as follows: Submission of an application for sterilization, a meeting of a commission on sterilization to decide whether to grant the application, and written confirmation from the patient that he or she had been informed of the repercussions of undergoing the procedure (as per section 11 of the directive).

The Czech Public Defender of Rights, in his report, summarized the terms for a lawful sterilization as follows: “When assessing the legality of sterilization performed on healthy sexual organs, the three requirements below should receive special attention:

- The application or consent of the person to be sterilized. The application (consent) must manifest the person’s free, serious and error-free will to undergo fertility elimination.

- Consent of the sterilization commission to sterilisation based on the objective existence of a medical indication according to the annex of the Sterilisation Directive.

- Consent of the person to be sterilized to the intervention, while such consent must be based on full and precise information on the nature and implications of sterilization.”

The law in practice and the open letter

After pressure and recommendations, especially from civil society, NGOs, international bodies and committees, and the victims themselves, in 2021 a law was adopted with broad political support that should compensate the victims of these illegal sterilizations. It has been in effect for almost a year, which is why we already know the current limits of its application in practice.

The Czech Health Ministry is tasked by the law with deciding on the applications for compensation within two months from the time the application is submitted, and the legislation expressly facilitates reference to evidential instruments other than original medical records. We are encountering a problem with these two points in practice.

For some applications, the deadline by which the decision should have been issued has been exceeded by 10 months without any decision being issued yet. Meanwhile, other applications submitted, for example, in July, have already been decided.

How the Czech Health Ministry is approaching these decisions and according to what rubric it is selecting the order in which the applications are to be answered is not absolutely clear. We warned of this problem already in an open letter in August.

“However much I might regret the situation of the department in question, the proposal for a solution that would consist of meeting the deadlines would be objectively impossible to implement in the short term, and the colleagues concerned know the legal deadline, so there is no need to draw their attention to it,“ Czech Health Minister Vlastimil Válek officially responded to our admonition in September. Those victims whose original medical records have already been shredded will, therefore, be unable to access compensation under the current practice.

The Czech Health Ministry is not even taking into account whether this shredding has been undertaken lawfully or not. The ministry claims it acknowledges other evidence besides original medical records that demonstrates illegality, but which kinds of other evidence would be considered sufficient by the ministry is not published anywhere.

For that reason, as of this writing, anybody who was forcibly sterilized before the year 1982 who applies for compensation will de facto be rejected (hospitalization records are only required to be maintained for 40 years). The law, however, was written with the intention of compensating anybody (including men, who comprise a very small group of these cases) who was sterilized in contravention of the law between the years 1966 and 2012.

The final problematic category are decisions that do not take into account the fact that the approach at issue broke the law. In more than one case, the medical records do not include written information about the nature of the surgical procedure as required by section 11 of the directive on sterilization.

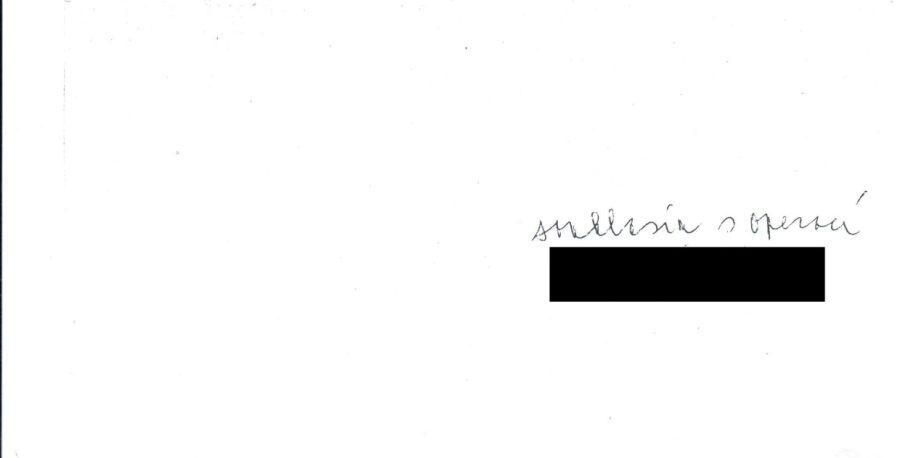

The absence of such edification of the patient, however, is not considered by the Czech Health Ministry to be problematic, and it has not expressed its view of the legal arguments submitted by the Human Rights League on this point as part of our clients’ applications. The most recent decision is a case where the medical records blatantly include a racial motivation for the sterilization, for which the “informed consent” was signed beneath a single, handwritten sentence reading “I agree with the operation” on an otherwise blank piece of paper, and where the records do not include anything about whether the patient was informed about the nature of the procedure.

The Czech Health Ministry asked its Department of Health Care to assess these records, and that department warned the ministry of all these deficiencies. Despite this, the application was rejected.

Conclusion

In cases where the application is rejected it is possible to file for remedy with the Czech Health Ministry and object to the rejection, but it must be done within 15 days. Already the Czech Health Ministry has received several dozen such objections, not one of which has been successful.

In the most recent case mentioned above, the Human Rights League is still waiting for a decision on the objection submitted. If that objection will also be rejected, we would then have the opportunity to file a motion with the Czech Public Defender of Rights, which is involved with this subject, as well as to file an administrative lawsuit within two months of receiving the rejection of our objection.

Here, however, it is necessary to stress that the option of taking legal action is frequently costly for applicants, and above all it means they must continue to wait for a decision. The law, therefore, is unfortunately not being enforced as an effective compensation mechanism of the kind that was hoped for by those who contributed to drafting it.