Czech educators told Romani child she was "slow" - in the UK she's on her second college degree and working as a dental nurse

Adriana Rácová comes from a Romani family in Ostrava, Czech Republic, one of five children who spent her childhood on a farm in a rural environment. Just like her siblings, she attended primary school in Ostrava where, according to her, her class teacher did her best to convince Adriana’s parents to reassign her to a “special school” because it would be “better” for her.

Adriana’s parents strenuously rejected that idea and Adriana successfully graduated from primary school. After the floods of 1997 the family lost their house and their land and were crammed into a small apartment in Ostrava as a consequence of the catastrophe.

The family later emigrated to England. Adriana discovered her passion for reading and study in that country.

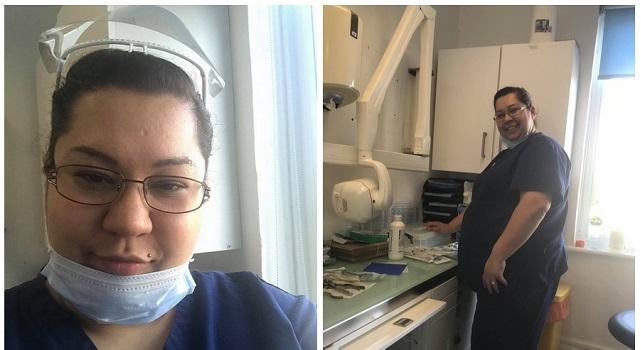

After graduating from an arts-focused high school there, she graduated from a college with a focus on dental hygiene and this September will matriculate to another university to train to become a dental therapist. None of this is easy, though.

From Monday to Friday the 34-year-old works as a nurse in a dental clinic and takes care of elderly people on the weekends. She is studying long-distance in the evenings.

When asked how she deals with such a schedule, she laughs and says: “I have wings, I can do it all.” She grew up in the Nová Ves area of Ostrava.

Adriana recalls her childhood as having been spent in a village. It was idyllic – for many years they were the only Romani family in the local community, her grandparents lived with them, and relationships with their neighbors were friendly, with people helping each other.

“We didn’t know what racism was. We never encountered it there,” she notes.

In 1997, when she was 14, the family lost their farm and home during the destructive floods. “We had a house in Nová Ves, a lot of land and animals, but we were no longer able to return there,” she recalls.

The family had to move into the city, into a single-room apartment at the Dubina housing estate. Their experience with those around them in an environment where nobody knew their family was a change.

“It was a shock for me and for my siblings,” she says. “People judged us at school, in the shops and on the street,” her sister Denisa says.

Like sardines

For the seven-member family with adolescent children the housing in the small apartment soon became unbearable. “We were not accustomed to living like that,” Adriana says.

At the same time they were grappling with financial problems. “If you lose all you have and you have no money for a new beginning, it’s difficult,” she says.

According to Adriana, in Ostrava it was difficult for her parents to find appropriate jobs at that time because her father encountered employers’ anti-Romani prejudices. This was despite the fact that he was a trained locksmith, spent years in the mines, and later worked as a maintenance man at the Labor Office.

Adriana’s mother was a nurse. Her father decided to try to get the family back on their feet financially and went to the USA to work for one year, where he made money as a waiter in golf clubs and restaurants.

After his return the family agreed to move to England. “Dad recognized that in America life was better and he didn’t like it in the Czech Republic anymore, he wasn’t succeeding with finding a job here. In those days many Romani people were emigrating to Canada or England,” Denisa says.

It was Denisa who triggered the family’s move. Her boyfriend decided to relocate to England and she followed him.

Her parents did not want their daughter to be alone there. “They said that if I was going there, they would too,” she laughs.

“We’re the kind of family that sticks together. If one of us goes somewhere, all of us go there,” Denisa says.

Nobody follows us around in the shops

After arriving in their new country the family did their best to join society as fast as possible. The children began to attend school, the family went to an intensive language course and then they found jobs.

Adriana studied art design at South Essex College. Her sister Denisa recalls the enthusiasm they all experienced during their first months in England.

They managed to save money while being able to indulge themselves in something they had never experienced in the Czech Republic. “When we went out, we were surprised that there are so many people of different nationalities getting along together. You walk into a shop and nobody comes after you, nobody turns around to watch you. It was fabulous,” Denisa says.

“I’ve been living here for more than 18 years, by now it’s my home,” Denisa says before listing the many successes achieved by her siblings. Her younger sister is completing university, while her brother studied social work and is now a physics teacher.

Denisa herself has completed two different secondary schools, is a social worker specializing in youth, and makes extra money as a waitress. “I work with British children who have different family problems or social problems,” she explains.

“Our own children are not experiencing any racism here. When we tell them what it was like in the Czech Republic, they are in shock. They can’t believe it,” Denisa says to us.

Ms Hitlerová

Despite her beginning difficulties with English, Adriana quickly oriented herself at school. Her fellow pupils contributed, to a great degree, to bringing her in and aiding her in the beginning.

Adriana began to succeed as a student in England. She did so despite the fact that when she had begun attending primary school in Ostrava she had to deal with a situation faced by many other Romani families.

“There was a teacher there whom we all called ‘Hitlerová’, and she did not like Romani people, she sent Romani kids to special schools,” Adriana says. That teacher did her best to convince Adrian’s parents to agree with such a reassignment.

Her parents emphatically rejected the idea. “Mom told her that her generation went to primary school and she did not see any reason why one of her daughters should go to special school,” Adriana says.

She transferred instead to a different class where the teacher supported her. In England, she says the approach at South Essex College was different.

“They accepted all of us kids as equals there. They did not make any distinctions. If somebody needed aid or was slower, they would call an assistant to explain or help,” she says.

It took her some time to grow accustomed to the new environment. “I couldn’t bear it here during the first six months,” she admits.

In the Czech Republic Adriana had studied German at primary school, but after arriving in England she could not understand anybody around her. As a result, she felt very isolated.

“I had to leave my friends at primary school, I had to leave the rest of my family. I protested against that,” she says.

Ostrava again

After getting settled and creating new social ties, the most difficult moment so far for the family arrived. Their father became seriously ill.

Adriana, her parents, and her younger siblings all moved back to Ostrava so her father could be examined and receive medical care. “That really destroyed me,” she says.

“I had already grown accustomed to it here [in England],” she recalls. She interrupted her studies and did her best to continue her education in the Czech Republic by attempting to enroll into a secondary school for the arts in Ostrava.

“I will never forget what happened when I walked into the principal’s office,” she recalls. “The principal thought I was a foreigner.”

“I explained my situation and that I wanted to study at their school,” she says. “He did his best to dissuade me in different ways.”

“It was weird,” she recalls. “Eventually I realized what was going on.”

“I asked him directly if the problem was that I am Romani,” she says. “He said: ‘Yes’.”

“I just turned around and left,” she recalls. “Then I became depressed.”

“I didn’t like how people behaved toward me on the street [in Ostrava],” she says. “One day I just got angry and went back to England.”

“By then I was more than 20 years old,” she adds. After more than a year her parents followed her back to England because they did not want to remain in the Czech Republic without their oldest children.

A careful student

After returning to England, Adriana completed her studies and decided to continue her education in a different field. She completed a three-year study program in health and social care, studied to become a dental nurse at Anglia Ruskin University, and as of September is planning to attend the University of Essex to become a dental therapist.

This is not an easy life, though. She works Monday through Friday as a nurse at a dental clinic and then takes care of elderly people on the weekends.

She is completing her studies long-distance through night school while working and taking care of her household. It has become necessary for her to create a strict daily schedule.

“I come home from work after 5, I cook dinner between 6 and 7, I clean up, and from 7 to 9 I am reading and studying,” she explains. Three years ago she had the good fortune to marry an Indian man living in England.

“We are of different religions – he’s a Hindu, I’m Christian. We do not force anything on each other, it works,” she says.

“He has his little altar at home and I have an image of the Virgin Mary,” she says. She feels very at home now in the small coastal town of Southend-on-Sea.

Adriana says she enjoys visiting her extended family in the Czech Republic but would not like to return there to live. She believes her husband could have problems with racism there because he is darker-skinned that she is.

“He was very surprised by that, he was not able to comprehend it,” she says. She does admit that much about the Czech Republic has changed since she moved back to England.

“When I was recently in Ostrava I was surprised that it was better than it used to be. When we went to a cafe they served us normally,” she says.

First published on the Czech Government’s HateFree website.