The anniversary of 17 November is over-saturated with historical content in the Czech Republic. Two milestones in the grand story of the history of the Czech nation happened on that day.

In high school we primarily learn about the symbolic meaning of the events of 17 November 1939, when university students in Prague commemorated the murder of their classmate Jan Opletal and the Nazis arrested and then murdered several student representatives in response. Ever since then, the November anniversary has been depicted as a brave act of resistance by the Czech nation against the Nazi totalitarian occupiers.

The more recent event, that of 17 November 1989, is symbolized in a similar spirit as the peak of resistance by Czech students to communist/Soviet totalitarianism. Both of these images seem to be very open-and-shut and difficult to impugn.

The moral lesson of these events is easy to recognize: Brave Czech students vs. the Nazis, who are conflated with all Germans in this image, and brave Czech students vs. the monstrous communist police obeying orders that were probably still coming from Moscow. A more detailed examination of the events of 1939, of course, breaks down these clear moral categories and relativizes them.

Of the nine student representatives executed by the Nazis, eight were members of nationalist organizations that had been active during both the First Republic (1918 – 1938) and the so-called Second Republic (1938-1939). Groups like Vlajka (Flag), inspired by Italian Fascism, or the youth group National Unity (Národní sjednocení – NS) and the Party of National Unity (Strana národní jednoty – SNJ) were paving the way for the order of the Second Republic with the ideas of a corporativist nation-state in which there was no room for foreign, non-national "parasites" or for groups or individuals who "avoided work".

It was Vlajka and the youth of the NS who emphasized biologically-determined national or racial affiliation in their program declarations and placed themselves in the role of defenders of the purity of the Czech nation. During the Second Republic the SNJ called for "special measures" and for individuals labeled as "Jew-Bolsheviks", "parasites", or "work-shy persons" to be stripped of their rights.

This call permeated the legislation adopted at the time and the measures that were planned. On the basis of such measures, "persons of Jewish origin" and others were excluded from socially important professions (doctors and lawyers) and were either designated for re-education in special disciplinary labor camps, or were harassed on a daily basis.

The open celebration of the memories of the brave students from November 1939, therefore, leaves an unpleasant taste in one’s mouth which can only be easily gotten rid of by completely throwing this history and the oppressive burden of the past far away from us, somewhere we need never revisit it. However, this commentary on 17 November also reveals its hidden, immeasurable potential.

Some local celebrities, wreathed with an aura of expertise (such as [economist] Tomáš Sedláček) are currently insisting that there is not the slightest connection between the economic crisis and Fascism and that we should not let ourselves fear such developments today. Indeed, a dangerous trend can be observed among both contemporary academic and popular productions of history.

The era of the Second Republic is usually completely marginalized, neglected, or else serves as an historical anomaly, the exception to the rule of the completely open-and-shut historical development of Czech national history toward democracy and freedom after 1989. Several authors are newly attempting to apologize for the behavior of the Catholic-oriented and right-wing nationalist literati who led that era’s campaign for purging and transforming society in the direction of an authoritarian state, and who desired such a state even before 1938.

Instead of asking why these people were capable of using the same vocabulary as the more intellectual publications of the Third Reich, we are instead seeing efforts to morally pass judgment on them in order to offer them absolution. This is why literary historian Jaroslav Med, in his "Literary Life in the Shadow of Munich" (Literární život ve stínu Mnichova) claims that the Catholic literati eventually acquitted themselves with honor during the clash between freedom and totalitarianism: They recognized the danger and they stood up against Nazism.

It is no accident that the current hierarchy of the Catholic Church in the Czech Republic is helping to promote such work. This is a completely logical step, given that Cardinal Duka has also given his auspices to Fascisizing events such as the so-called "March for the Family" here.

It is as if even today it is still socially unacceptable for experts to ask why society so easily introduced measures excluding persons of Jewish origin from public life at that time, why they began building not just labor camps for the unemployed, but also planning disciplinary labor camp facilities for correcting and re-educating "degenerate individuals." It seems that instead of providing a more substantive answer to this question, it is still enough to just wave one’s hands and refer to this as having been necessary due to pressure from the Third Reich.

Evidently it remains necessary to preserve a sharp dividing line between the bright, democratic, positive First Republic, which we are supposed to view with admiration, and the dark, negative and un-free Second Republic. The first allegedly represents the "natural" development of Czech national history, while the second represents a pathological development.

However, the answers to these questions – why Czech society so easily, quickly, and smoothly accepted measures intended to introduce Fascist rule – lead us to discover the continuous elements between these opposite poles. When articulating the heretical thesis that not just the ideas, but perhaps even the legislation of the Second Republic’s order can be found already during the era of the idyllic First Republic, the hidden topicality of the past rises before us: By "Fascism", we must mean only Adolf Hitler and the Nazis – or can we also label their opponents Fascists as well, people who merely desired that same Fascist "national sanitation", who wanted to take into their own hands the establishment of who exactly could be labeled a "parasite"?

The journal National Liberation (Národní osvobození) has a long tradition reaching back to the First Republic and to the Legionnaire’s organization, and was a fundamental pillar of the legitimacy of interwar Czechoslovakia. Today it is a periodical of the Czech Freedom Fighters’ Union (Český svaz bojovníků za svobodu – ČSBS), and it has recently published a piece which can be read as a disturbing testament to the dysfunction of current recollections of the struggle against Fascism.

In this article, a member of this organization exploits a comparison between the past and present to claim that, just as our interwar Czechoslovakia was disintegrated from within by the German minority, now our Czech Republic is being economically overthrown by the Romani minority. He goes on to propose that at EU level, someone should repeat to the Romani minority the alleged statement of former Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard, which has been making the rounds online since 2005, about inhabitants perceived as "non-indigenous", i.e., asylum-seekers, immigrants and other wanderers: "We didn’t invite you to our country. We don’t need you. If you want to live here, you must adopt our culture and get in line. If you don’t do this, you will have to leave."

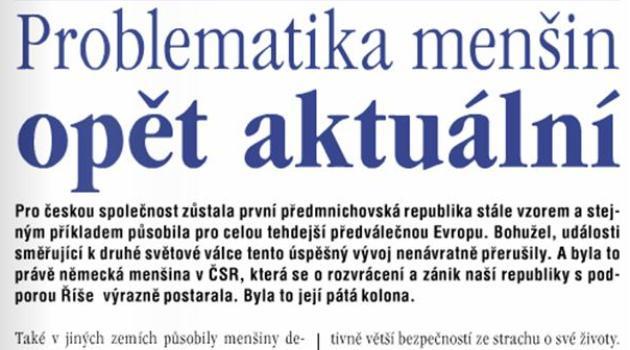

The piece, entitled "Issue of minorities topical once more" (Problematika menšin opět aktuální) was authored by Jaroslav Bukovský, chair of the Czech Freedom Fighters’ Union cell in Plzeň, and was published in the 9 October 2013 issue of Národní osvobození, number 21, page 3. Bukovský argues that just like the "politically unreliable" citizens of the First Republic, practically all of whom were members of the German minority at the time, today the "inadaptables", the Romani minority, represent an unacceptable security risk and must be pacified.

How is this domestic, proud-anti-Fascist/veteran any different from a sympathizer of the Workers’ Social Justice Party (Dělnická strana sociální spravedlnosti – DSSS) that has been marching through the towns of this country recently? Bear in mind that my aim in asking this question is not at all to label the entire Czech Freedom Fighters’ Union a Fascist organization.

Rather, it is necessary to understand that the proponents of Fascism today are not just neo-Nazis denying the existence of the gas chambers and other apparently lunatic fringe, obscure groups, but that they can even be people hiding in an organization boasting the veteran aura of those who actually fought the Nazis. The media calls them anti-Fascists, their representatives speak during important anniversaries, and they have an influence over the instruction of history in the schools.

If even some of these so-called anti-Fascists are helping to stir up antigypsyism, can we be surprised when high school students, during a mock election, give a number of their votes to the DSSS? Can we be surprised by the radical solution to the "Romani question" that is proposed by the gustily politically incorrect [Czech Senator] Tomio Okamura?

Is it really so surprising that representatives of all parties, across the political spectrum, independent of their allegedly left-wing or right-wing focus, agree on the "Romani problem" and make proposals to restrict civil rights at local level? Racism is a social problem, and we keep repeating this same old truth over and over again.

Racism will be here as long as we are satisfied with a system which rewards some with salaries in the hundreds of millions for their "responsible work" and leaves others to live rough, without employment or the means for the barest of existences. The fact that it is possible to so easily band all social problems together through talk of "inadaptables" and "parasites", however, is also a side effect of our inability to take the contemporaneity and history of Fascism seriously.

In such a situation, is it possible to expect that a celebrity in the media environment will lift up his or her voice and speak for us? The time has come to move out from beneath our own shadow, to stand up and express our dissatisfaction with this state of affairs, not only in Czech society, but also in the direction of many other European countries and their policies.

We must renew the meaning of anti-Fascist opinions as the active, daily manifestation of a civic position. We must cease to remain silent when we hear the favorite jokes about Hitler’s biggest mistake, or the elitist, snobby ridicule by pseudo-intellectuals of the activities of obscure neo-Nazi groups.

The anniversary of 17 November brings us the opportunity to change our relationship to the past. We can show that commemorations still make a difference.

Of course, it must be emphasized that this difference is made only in relation to the lived present. We can even remember without wreaths and in other ways than by bowing our heads graveside.

17 November is an opportunity to express solidarity, for example, with the anti-Fascists who were murdered during the course of this year all over Europe. We can remember the names of those who were beaten up or beaten to death by Czech nationalists and neo-Nazis.

We can express solidarity with refugees in Greece, who face racist attacks daily, not just by the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party, but also by local police officers. We can fiercely reject legislation criminalizing those without a roof over their heads.

In other words, we can express solidarity with all groups who are denied equal treatment in Europe and in the world. Let’s meet up on 17 November 2013 at 14:00 on Jungmannovo Square in Prague!

This piece was first published by Deník referendum.