The forgotten Holocaust: Romani victims of the Holocaust and their place in the Czech past and present

On 27 January 1945 the Red Army liberated the complex of Nazi concentration camps at Auschwitz, where millions of people from all over Europe suffered and died. Among them were the Romani children, men and women in the so-called "Gypsy Family Camp" in one section of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The Roma in that part of the camp did not live to see it liberated. The last of them, almost 3 000, had been sent to the gas chambers several months prior, at the beginning of August 1944.

This was the horrible culmination of the Nazis’ so-called "Final Solution to the Gypsy Question". Several hundreds of thousands of Romani people fell victim to this policy in Europe.

Law on "wandering gypsies"

The beginnings of these tragic events, however, are not connected with the rise of Hitler to power, as they might simplistically seem, but just as in the case of the Jewish population, what happened to the Roma has its roots in many centuries of notions and prejudices about them that Europeans have maintained and nourished. The manifestations of these notions have varied depending on the place and time.

As an example of one specific approach, we can consider the Czechoslovak law "on wandering gypsies and persons living the gypsy way of life" from the year 1927, which forced a completely vaguely-defined population group to use the so-called "gypsy identification cards" and subjected them, among other things, to constant police harassment, restricted their freedom of movement, and banned their entry into many towns and villages. More radical measures against Romani people began to be applied practically immediately after the rise of the Nazis to power in neighboring Germany and gradually spread to other European countries.

The German Nazis’ procedures were defined and designed with the aid of the Nazis’ racial science produced by a special racial-hygiene institute in Berlin and were put into practice through various political measures that resulted in forced sterilizations and the internment of Roma in collections, labor and concentration camps. The burgeoning radicalization manifested itself on Czech territory as well, where in December 1938 the District Governor in Poděbrady proposed that the Regional Office in Prague "unanimously establish concentration camp facilities for gypsies and vagabonds", and on 2 March 1939 the Czech-Slovak Government actually did approve a bylaw on disciplinary labor camps.

"Gypsy camps"

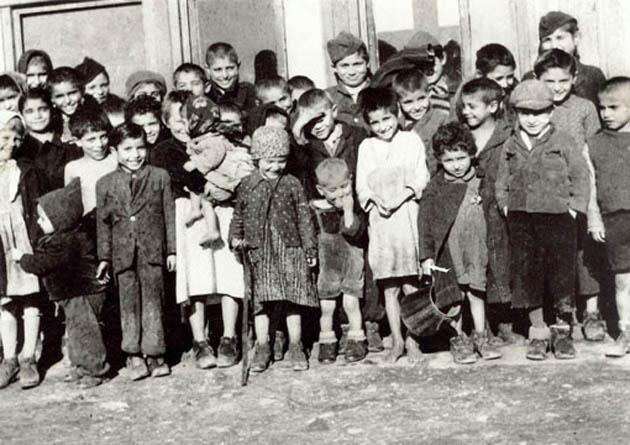

The subsequent "anti-gypsy" measures carried out by the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia were based on practices used during the Czechoslovak First Republic, and an openly racial policy was then implemented that copied the procedures that had been used by the Germans up to that point. In addition to banning the traveling lifestyle, and in addition to placing some Romani men into disciplinary labor camps, the year 1942 introduced a basic watershed when the special "gypsy camps" were created for the concentration of Romani children, men and women from Bohemia (at Lety by Písek) and Moravia (at Hodonín by Kunštát).

About one-third of the 6 500 "gypsies and gypsy half-breeds" listed in a census were gradually imprisoned in these camps as of 2 August 1942. The rest of those listed in the census remained outside the camps with restricted freedom of movement and under constant police surveillance for the time being.

In comparison with the concentration and extermination camps, the camps at Hodonín and Lety may not seem very important, but with respect to the history of the native Czech Roma and Sinti, they are of enormous significance. In both of these camps, children, men and women suffered and perished under horrible conditions "just" because of their origin, in the country of their birth, and through the assistance of their fellow citizens.

Auschwitz

The final phase of the so-called "Final Solution to the Gypsy Question", therefore, was the so-called "Auschwitz Decree" of 16 December 1942 by SS leader Himmler, which affected many more people than just the Roma in the Protectorate. Himmler decided through that decree to intern Romani people at the concentration and extermination camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

From the start of March 1943, several mass transports gradually left the Protectorate full of prisoners who were not just from both of the "gypsy camps", but also taken from most of the Roma who had been living outside the camps up to that point. Romani people from many European countries directly controlled by the Nazis were imprisoned at Auschwitz-Birkenau in a special section, B-II-e, which was called the "Gypsy Family Camp" because, unlike other parts of the Auschwitz complex, Romani families were kept together there.

Gradually more than 22 000 Romani children, men and women were interned there. Roma from the Protectorate represented more than one-fifth of the prisoners there and were the second-largest group of prisoners after those from Nazi Germany (including occupied Austria and the Sudetenland).

A possible but very uncertain hope for saving oneself was to be transported to another concentration camp, whether one close by or further away. However, such transports were only for prisoners who were capable of working and who were more robust.

Moreover, in those other concentration camps thousands of people still fell victim to hard labor and various medical experiments. The fate of Auschwitz’s "gypsy camp" was ultimately decided in the spring of 1944.

A final action was undertaken several months later, after the last transport of men to Buchenwald and women to Ravensbrück had been performed; during the night of 2 August and the early morning hours of 3 August, the rest of the prisoners of the "gypsy camp", almost 3 000 people (primarily children, the elderly, the ill and women), were forced into the gas chambers. Of the overall number of more than 5 000 Bohemian and Moravian Roma imprisoned at the Auschwitz complex and in other camps, only about 600 returned to that part of Czechoslovakia after liberation.

The Nazi terror, therefore, was survived by only about 10 % of the Roma native to the Czech lands. In addition to these survivors, several Romani families and individuals who had been mainly hiding in Slovakia during the occupation also returned to the Czech lands after the war.

Some had managed to avoid deportation with the aid of non-Romani friends and neighbors or by paying bribes. The genocide of the Bohemian and Moravian Roma was probably one of the most thoroughly performed genocides of the Second World War, as they were almost completely murdered off.

A forgotten Holocaust

These events were nevertheless forgotten for many decades after the end of the war, both in the countries of the Eastern Bloc, which were not interested in opening up the topic of the ethnicity of "persons of gypsy origin", and in the West, where prejudices against Romani people persisted and where for many years they were considered persons who had been persecuted by the Nazis because they had committed crimes. Even though starting in the 1970s the absolutely fundamental, ground-breaking works of the Brno-based historian Ctibor Nečas were published (e.g., his publication "On the Fate of the Czech and Slovak Gypsies" from 1981 – Nad osudem českých a slovenských Cikánů – or his 1987 Andr´oda taboris, subtitled "Prisoners of the Protectorate Gypsy Camps 1942-1943" – Vězňové protektorátních cikánských táborů 1942-1943), it was not until after the fall of the communist regime that representatives of the media, the public and the state began to take an interest in the Czech lands in the topic of the Romani Holocaust.

Gradually, public commemorations, education and research into the Romani Holocaust began to take place. Commemoration ceremonies are regularly held at the sites of the Protectorate-era camps and elsewhere, and the topic turns up in exhibitions, expert publications, lectures and schoolteachers’ interpretations of Czech history.

However, this process is definitely not over and there is still much to be done, mainly in the field of education. The pupils and students at primary and secondary schools, as well as at colleges, should learn about the fate of the Roma during WWII, but not just about that.

It is not possible to discuss the Romani Holocaust without knowledge of the Romani people’s previous customs, history, traditions, ways of making a living, etc. Of course, it is important to educate not just pupils, but the pedagogues themselves, whose college educations must sufficiently prepare them to teach about this topic.

The issue of the reverent commemoration of Romani victims is also essential. Everywhere in the civilized world, the victims of the Holocaust are shown respect and the sites of their suffering are preserved in as dignified a way as possible.

Currently the recreation center located at the site of the former camp at Hodonín by Kunštát is being transformed by the Czech state into a dignified memorial, but at the site of the camp at Lety, a disgraceful industrial pig farm is still in place. While elsewhere in the world the date of 2 August, commemorating the clearance of the "gypsy camp" at Auschwitz, has been declared the International Day of the Romani Holocaust and is an important state holiday in Hungary and Poland, no symbolic act of such significance has been undertaken by the Czech Republic.

An important place in the process of coming to grips with the past, naturally, is occupied by expert research and the public discussion based on it. The historical facts about the Romani victims, however, have frequently been twisted here, and several Czech politicians have even intentionally cast doubt upon the Romani victims of the Holocaust.

The question of the approach taken by the majority Czech society to the Romani Holocaust corresponds, to a significant degree, to their approach to Romani people per se. Until the Romani minority is perceived as an equal part of Czech history and society, the topic of the Romani Holocaust will remain marginalized and overlooked.