ROMEA to Czech President: Romani life in communist Czechoslovakia included forced assimilation, forced sterilization of women, segregated education

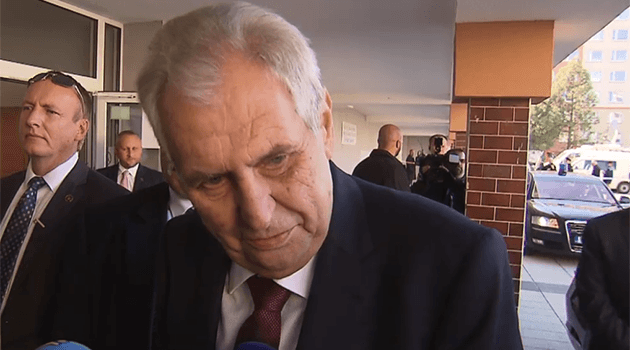

Speaking on Friday after casting his ballot for an interview with Richard Samko, a Czech Television reporter who is a Romani community member, Czech President Miloš Zeman reiterated that Romani people – unlike other citizens – did not suffer so much during the communist era. “What kind of nationality can this be if the nation cannot even manage to espouse its own nationality and instead of that lists themselves [during the census] as Slovak, Czech, Hungarian, I don’t know what all,” Zeman also said during the interview.

When Samko objected that the hesitancy to self-identify is because of Romani people’s historical experience and fears associated with the country’s Nazi- era and communist-era past, the President said: “That’s a terribly long time ago, though, and as far as the communist past goes, unlike other people here, the Romani people didn’t suffer that much during communism.” In order to better inform the public, news server Romea.cz has decided to publish an overview below of information about what the lives of Romani people in Czechoslovakia during the communist dictatorship involved.

From the Holocaust to imprisonment for living on the road

Romani people have been living in the Czech lands for at least 800 years, with the first known written mention of them dating to the mid-13th century. In 20th century history, in addition to the Nazi German-organized Holocaust of the Czech Roma (during the war almost 90 % of Romani people from Bohemia and Moravia were annihilated), the experience that impacted Romani people the most was their forced assimilation by the communist regime.

That assimilation attempt was begun by the adoption of a law about the “permanent settlement of traveling persons” which took effect on 11 November 1958. The discriminatory legislation threatened all who lived itinerantly with imprisonment and that aspect of the law was not removed from the Czech legal code until 1990; the law itself was not abolished completely until 1998.

The 1958 law caused drastic interference with the living conditions and customs of Romani people, and not just of the groups who were still traveling up until that time, above all the Olah (Vlax) Roma. An “inventory” conducted in 1959 also affected Romani people who were already settled but who commuted over long distances between their family homes and their workplaces and who therefore spent periods of time away from their permanent registered address.

“Permanent settlement” at that time meant relocating Romani people to live in predetermined housing and to perform predetermined jobs. Whoever did not accept this “aid” from the state would be imprisoned.

Forced assimilation, denial of ethnic identity

The “solution”, as communist rhetoric referred to it, to the so-called Romani “problem” was, in the view of the regime, assimilation, i.e., the adaptation of Romani people’s actions, appearance and behavior to conform to the image of a “properly working citizen” and to deny their ethnic identity. Many of the consequences of that law, along with the socialist state’s Romani policy, are apparent to this day.

Today’s ghettos in the Czech Republic and Slovakia have arisen in the exact same locations where Romani people were forcibly relocated around the republic and segregated into quarters of towns that were rendered relatively inaccessible. From the beginning of the 1960s, what used to be called “National Committees” also introduced their own special lists of the Romani people residing in each individual locality.

In 1965, on the basis of a Government resolution, it was decided to “disperse” members of the Romani population in terms of where they were allowed to live. A Government “Committee on the Gypsy Population Question” was established, the aim of which was to bring the socioeconomic level of members of the Romani population into balance with the level of the rest of society and to achieve their integration.

One component of those plans was the demolition of Romani-inhabited neighborhoods, settlements (above all in East Slovakia) and streets and the subsequent relocation of their residents, with the aim of dispersing the Romani population across all of Czechoslovakia evenly – but mainly in the industrial areas of North Bohemia and North Moravia. About 3 000 Romani families were redistributed around Slovakia and 494 families were relocated to Bohemia and Moravia.

By 1970, 109 of the Romani families relocated to the Czech lands had returned to Slovakia. Inside the Czech lands, the demolition affected 49 “undesirable gypsy concentrations”, in the parlance of the day, and required the relocation of 435 families.

Inferior jobs for Romani people

That plan was executed until the year 1968. On the one hand, it resulted in demolishing the Romani settlements that were the very worst from a public health and social perspective, but on the other hand it disrupted the tradition social bonds within Romani communities.

The relocation also destroyed the scale of traditional values that used to apply within Romani communities. The Romanes language and traditional Romani culture were labeled anachronistic and Romani people were urged by the state not to speak Romanes with their own children.

Most Romani people lacked any kind of officially certified qualifications, and for that reason they were assigned the most inferior jobs, frequently working in short-term positions with no job security or as seasonal laborers, and very often not comprehending that something like a legal duty to work on a daily basis even existed. In areas where Romani people were forcibly settled in such precarity the crime rate grew, both in terms of property crimes and violent crimes, as did the number of cases of “parasitism”, or cases of Romani persons convicted of having breached their obligation to work.

Romani children in the “special schools”

Romani children were assigned to “special schools”, the graduates of which were barred by law from pursuing higher education and were frequently also taken away from their birth families and institutionalized in state-run children’s homes. The policy of relocating Romani people and the attempts to integrate them continued during the 1970s and 1980s (often against the will of the Romani people involved and without taking into consideration their bonds to members of their extended families or specific groups) and as a consequence, this led to the segregation of the Romani minority in all respects.

The state began to provide eligible Romani people with welfare benefits in an effort to raise their social level. This policy decision cultivated Romani people’s reliance on the state for many aspects of their livelihoods.

Charter 77 stands up for the Roma

Not long after it was established, the Charter 77 organization expressed its views of the ongoing problems being associated with Romani people and their systematic degradation. “The so-called ‘solution to the gypsy question’ is predominantly limited to repressive measures that frequently take the shape of statewide campaigns that the majority population never learns about,” the group reported in a document from December 1978, adding that “the main barrier to addressing the so-called gypsy issue in Czechoslovakia today are disruptions of the majority society.”

Forced sterilizations

Fourteen years ago the forced sterilization of Romani people began to be spoken of once again by Czech society to a greater extent than previously. In September of 2004 the European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC) in Budapest published its suspicions that Romani women in the Czech Republic were still being forcibly sterilized.

The ERRC reported that cases had come to light in which the women concerned had never given their free and informed consent to the surgery or had been asked for their consent under extreme circumstances (such as during labor) or under the threat of cutting off their welfare benefits, for example. According to various studies, Romani women had been offered the option of sterilization since 1959 in Czechoslovakia.

Czech ombudsman Otakar Motejl said in 2005 that the illegal sterilizations of Romani women in the Czech Republic after the end of the communist regime represented relatively rare failures by doctors to secure their patients’ free and informed consent to these surgeries. In March of this year, the then-UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Prince Zeid bin Ra’ad Zeid al-Hussein, commented on the issue of compensation and redress by the Czech state for these human rights abuses as follows: “In the Czech Republic I am deeply disturbed by discrimination against Romani people and the long-term segregation of Romani children in the schools, which according to the EU has not changed since 2011. I am also joining the call for the compensation and redress of the thousands of women, most of them Romani women along with others, such as women living with disabilities, who have been forcibly sterilized there from the 1960s until 2004.”