On the 104th anniversary of Czechoslovak independence, recalling the Romani experience of exclusion

The Czech Republic is commemorating the 104th anniversary of the birth of Czechoslovakia as an independent republic with ceremonies in Prague and elsewhere, as is traditional. This morning, the representatives of the state commemorated the anniversary of Czechoslovakia's founding at the National Memorial on Prague's Vítkov Hill, as is also traditional.

At noon, Czech President Miloš Zeman was scheduled to appoint new generals at Prague Castle. This evening, Zeman will award state honors for the last time in Prague Castle’s Vladislav Hall.

What was it like, though, during the First Czechoslovak Republic for Romani men and women? The constitution of the Czechs’ and Slovaks’ common republic was democratic and introduced official recognition for many national minorities, but not for Roma.

The immediate aftermath of the birth of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918 at first did not introduce any more substantial changes for Romani people. The Austro-Hungarian legal norms continued to be applied against them in Czechoslovakia.

The most important norm was a decree issued by the Interior Ministry in Vienna on 14 September 1888 summarizing the anti-Roma measures in force. That decree concerned deporting foreign nationals who were Romani and defined how Romani people living on the road should be moved on and punished.

The law also regulated the issuing of documents for Romani people domiciled in the empire. In Hungary, a similar regulation was not issued until 1916, and in a milder form.

The Law on “Wandering Gypsies”

In the early 1920s, petitions began appearing in rural communities calling for the adoption of a law that would further limit the movements of Romani people. The consequence of those calls was not just the undertaking of a “head count” of Romani people in 1925 (numbering a total of 64,938 people: 62,192 in Slovakia, 1,994 in Moravia, 579 in Bohemia and 79 in Silesia), but also the adoption of Act No. 117/27, Coll., on “Wandering Gypsies”, dated 15 July 1927.

The findings of the “head count” likely underestimated the actual numbers (according to estimates, there were between 70,000 and 100,000 Romani people living in Czechoslovakia at that time). “In 1927, new legal norms were promulgated that regulated the approach to the ‘gypsy’ population, but to be more precise we should say that what was regulated was the approach to tormenting them,” director of the Museum of Romani Culture Jana Horváthová told Czech Radio.

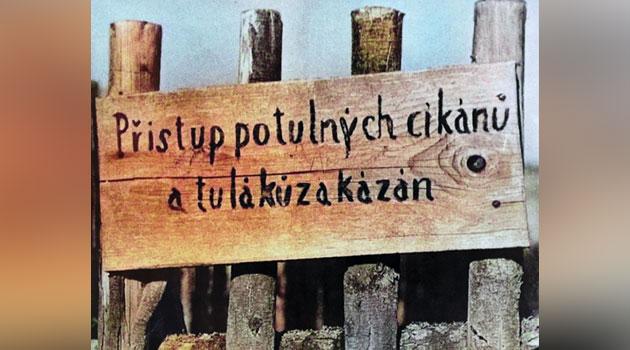

“That law made it possible to designate territories which the ‘wandering gypsies’ were forbidden to enter. These were big cities, recreational spaces, spa towns,” the director said.

“The legislation also facilitated removing children from their families for so-called ‘good re-education’. To make a long story short, the law restricted Romani people to the fringes of society even more,” she said.

The Czechoslovak law was modelled on a 1912 French law on those living on the road, as well as a 1926 Bavarian law “on gypsies and drifters”, and in general, Czechoslovak law on “the gypsy question” was among the most thorough and was described as exemplary throughout the 1930s at international conferences on criminal justice. The Agrarian Party was the chief initiator of the legislation.

“Head count” of the “wandering gypsies”

On the basis of that law, between 1928 and 1929 a “head count” of “wandering gypsies” was undertaken, and the Headquarters for the Registration of Wandering Gypsies (Ústředí pro evidenci potulných cikánů) used its findings to issue “gypsy identification cards” to all the persons captured by the survey; by 1938, Czechoslovakia had issued about 36,000 pieces of such identification. The implementing regulation to the law established the locations that forbade access to their territories by those holding such identification (especially Brno, Prague, and some spa towns).

The “Law on Wandering Gypsies” and the forced registration resulting from it particularly affected the Czech, German and Vlax Romani groups. The “head count” recorded members of those groups for whom it was natural at that time, in accordance with their traditional ways of making a living, to live either fully on the road or as residents who were semi-settled.

The law’s wording and the enforcement of its bylaws in practice sparked some criticism already in its day. “Ladies and gentlemen! The law on gypsies here before us is not just an exceptional piece of legislation, but also an unconstitutional one. […] According to this law, all gypsies will be stigmatized, almost without exception, as chicken thieves. The rapporteur, Mr. Viškovský, has declared that this law had to be drafted because all gypsies – he was making a generalization – refuse to work, avoid work and are lazy,” said Irene Kirpalová of the German Workers’ Social Democratic Party in the Czechoslovak Republic when the bill was being discussed.

From the perspective of today the law is unequivocally assessed as discriminatory, and it is essential to realize that through this legislation, people were registered who somehow showed signs of living as if they were “gypsies” but who actually were not Romani people. On the contrary, many Roma did not live like “gypsies”, from the law’s perspective.

During the First Czechoslovak Republic, as part of the continuation of previous historical developments, most Romani people were settled, especially in Moravia and Slovakia. Hungarian and Slovak Roma who were settled had applied themselves in Czechoslovak society as craftspeople and petty traders who were much sought-after, especially as blacksmiths, farriers, and manufacturers of baskets, brooms, products made of corn husks or unfired bricks, etc.

However, it was quite difficult to make a living from such crafts. “Romani people in those days were quite badly off,” Horváthová said.

“They were literally in need, in poverty, because by then the Roma could no longer make a living through their ancestral crafts,” the director of the Museum of Romani Culture said. It remains a fact of history that Romani people did not own and therefore did not cultivate any bigger plots of land and had to make do with the plots that they did own just for their own housing.

The first educated Romani people

On the other hand, the First Czechoslovak Republic was the time when some Romani people earned secondary and university educations: Tomáš Holomek of Svatobořice, for example, successfully graduated from Charles University’s Faculty of Law in Prague in the year 1936. “My grandfather Tomáš was born in 1911 in a Romani settlement,” Horváthová recounted for Czech Radio.

“The inhabitants of that settlement, and his family in particular, had to fight with the authorities for 100 years to win their place in mainstream society. That was quite difficult,” the director of the Museum of Romani Culture described.

“My grandfather recalled that life in the settlement was quite appalling in terms of conditions,” she related. In 1926, the first Czechoslovak school for Romani children was established in Uzhhorod (today Ukraine), built by Romani people themselves.

Czechoslovak President Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk personally contributed to that project. “Masaryk was a philosopher,” Horváthová told Czech Radio.

“We know how he got involved in combating the anti-Jewish campaign during the Hilsner Affair and how very positive it was that he did. We assume that was his overall approach to people per se,” the director of the Museum of Romani Culture said.

“However, we can also say, for example, that he contributed personally to building the ‘gypsy’ school in Uzhhorod. That was Czechoslovakia’s first ‘gypsy’ school,” she related.

During the 1930s, a music school for Roma was established in Košice (today Slovakia), and questions related to the lives of the Roma began to be studied by some educated Czechs (the India Studies scholar V. Lesný and the pedagogue F. Štampach). Despite the discriminatory “Law on Wandering Gypsies” and other legal measures, the gradual integration of Romani people into society, which had already begun in the 19th century, was clear to see as the 20th century progressed.

Sources used

- Petr Lhotka, skola.romea.cz

- Nečas C., Romové v České republice včera a dnes, Olomouc 1995

- Nečas C., Nad osudem českých a slovenských Cikánů 1939 – 1945, Brno 1981

- Šípek Z., Řešení situace potulných Cikánů v českých zemích v letech 1918 -1940. Neznámý holocaust, Praha 1995

- Thurner E., Zigeunerefeindliche Massnahmen in der Zwischenkriegszeit, Praha 1995