Ninety years ago the Czechoslovak authorities issued law on "wandering gypsies", took fingerprints for "gypsy identification cards"

Ninety years ago, the Chamber of Deputies of the National Assembly of the Republic of Czechoslovakia approved a law “on wandering gypsies” on 14 July 1927 that took effect as Act 117/1927 Coll. and remained on the books until the year 1950. According to its first paragraph, the law was meant to apply to “wandering gypsies”, defined as “gypsies wandering from place to place and other vagabonds avoiding work who live the gypsy way of life.”

In the ministerial documents of the time, police orders, and handbooks for the gendarmerie, the district authorities and gendarmerie stations that were meant to enforce the law were called upon to consider practically all Romani people as “wandering gypsies”. Travelling, according to these documents, was allegedly “an inborn instinct” or even a “racial feature” of Romani and Sinti people.

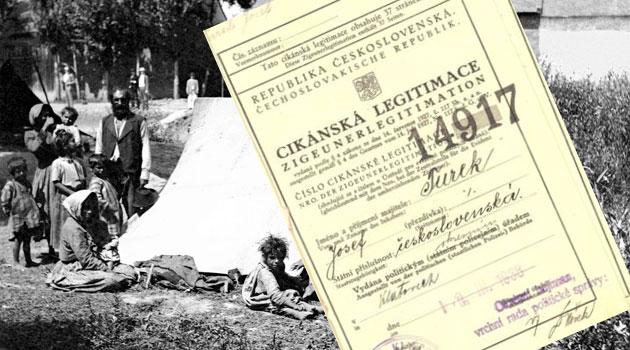

The legal concept of a “wandering gypsy” was, in practice, customarily replaced by the general term of “gypsies”. The law had a total of 21 paragraphs and required persons 14 years of age and older to have and produce upon request a so-called “gypsy identification card”, a special document including not a photograph, but the owner’s fingerprints.

Such documents were one component of a special set of police records based on fingerprints. “Wandering gypsies” were, as a group, listed in those records alongside dangerous criminals and recidivists.

Travelling was permitted only with official, special permission, the so-called “travel paper”. The law further restricted the size of groups that travelled and banned them from possessing weapons.

Local authorities had to set aside a place on their territories appropriate for camping, but also could ask for “wandering gypsies” to be banned from entering their area. Paragraph 12 of the law states that it is within the competency of the district courts to remove children younger than 18 from Romani parents and place them with foster families or into institutional care.

The law had a total of 21 paragraphs and required persons 14 years of age and older to have and produce upon request a so-called “gypsy identification card”, a special document including not a photograph, but the owner’s fingerprints.

Before the law was adopted a debate was held in the Chambers of Deputies about the bill, which was drafted by bureaucrats of the Interior Ministry and police, where both agreement with the law and objections to it were heard. Among those objecting was an MP for the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, József Gáti, who in 1944 was deported to Nazi Germany and never heard of again.

In one part of his speech on this issue, Gáti said: “The gypsy identification cards are nothing different to what the yellow fabric was for Jews in the Middle Ages, or female prostitutes’ identification. By means of this characteristic ruthlessness, which under the pretext of preventive measures will label innocent persons and trample on their personal freedoms and the equality guaranteed to them by the Constitution, the masses of this unfortunate race will be criminalized, mainly, itinerant seasonal workers.”

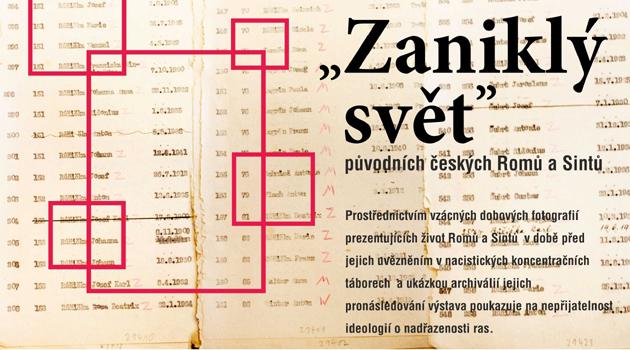

“The law ‘on wandering gypsies’ meant that all Romani and Sinti people living in Czechoslovakia at that time, whether settled or travelling, could be placed by the state authorities at any time at the level of hardened criminal recidivists. On the basis of those special police records based on fingerprints, the Czechoslovak gendarmerie, during the 1930s, claimed they were best-positioned to authoritatively describe the lives of Romani and Sinti people in Czechoslovakia. By that time, at the latest, the gendarmerie’s descriptions had been connected with those practicing anthropology, who in those days classified humanity into groups, races, according to physical characteristics, and assigned them to an evolutionary scale of the development of the human species ranging from primitivism to civilization. The gendarmerie’s descriptions of the ‘biology of gypsies in the Czechslovak Republic’ demonstrate that the gendarmerie considered ‘gypsies’ to be a backward or primitive race,” says Pavel Baloun, a historian and doctoral student at the Department of General Anthropology, Faculty of Humanities, Charles University in Prague, who is the author of several articles about the reasons the law arose, its content, and the consequences of its adoption.

The Terezín Initiative Institute has now published materials about this history to mark the 90th anniversary of the publication of the law “on wandering gypsies” on the educational online portal holocaust.cz. The articles there (in Czech only so far) discuss this history in greater detail.

“Unfortunately, after 90 years, it is difficult for us to find eyewitnesses to these events during the First Republic, or the descendants of eyewitnesses, especially when we take into consideration the fact that the vast majority of the inhabitants to whom that law applied became the vicitms of racial persecution by the Nazi regime just a few years later. Almost no written memoirs of those events have been preserved. It is, therefore, very difficult to ascertain what the precise impact was of this law on Romani families. The texts we are now publishing on the website are part of our project creating a Database of Romani Victims of the Holocaust, which the Terezín Initiative Institute has been working on since 2016, drawing on the know-how we have accumulated during our 20 years of work documenting the Jewish victims of the Holocaust,” says Eliška Waageová, an expert staffer and editor working for the holocaust.cz website.

Romani and Sinti Holocaust victims have been commemorated by the Terezín Initiative Institute for the last several years as part of its annual public reading of the names of victims of the Holocaust – Yom HaShoah. Last year the Institute joined the commemoration of Roma Genocide Remembrance Day, which will take place this year on Wednesday, 2 August in Prague.