Mass in Prague tomorrow, 15 October, for the late Ing. Karel Holomek, to be celebrated by Tomáš Halík

On Sunday, 15 October 2023 at 14:00 a mass will be said for the late Ing. Karel Holomek in the Church of the Most Holy Savior in the Clementinum complex on Křižovnická Street in Prague. Tomáš Halík will be the celebrant.

On this occasion we are publishing in full translation the eulogy for Ing. Holomek written by his daughter, the director of the Museum of Romani Culture, Mrs. Jana Horváthová, which was previously published in Czech for the September edition of Romano voďi magazine.

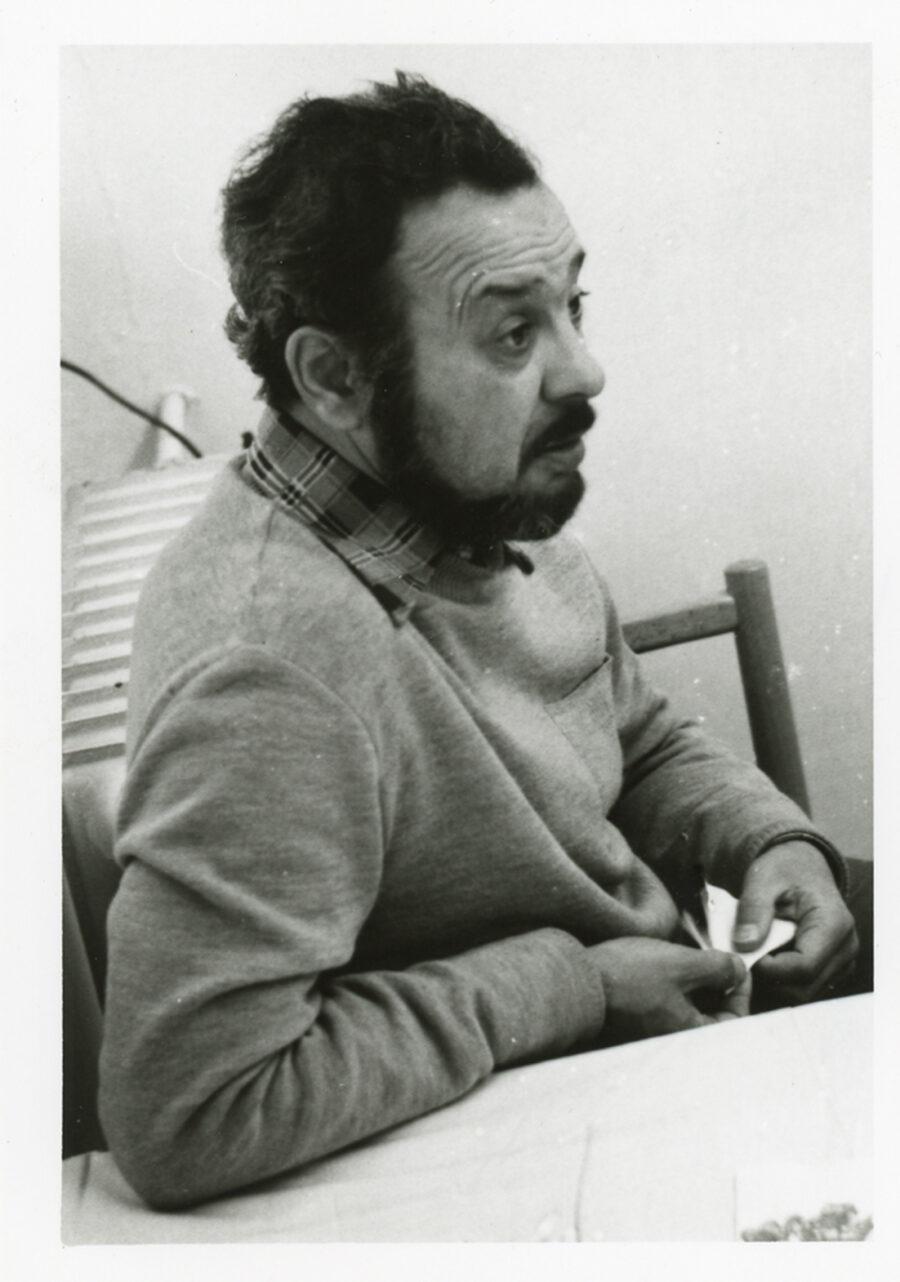

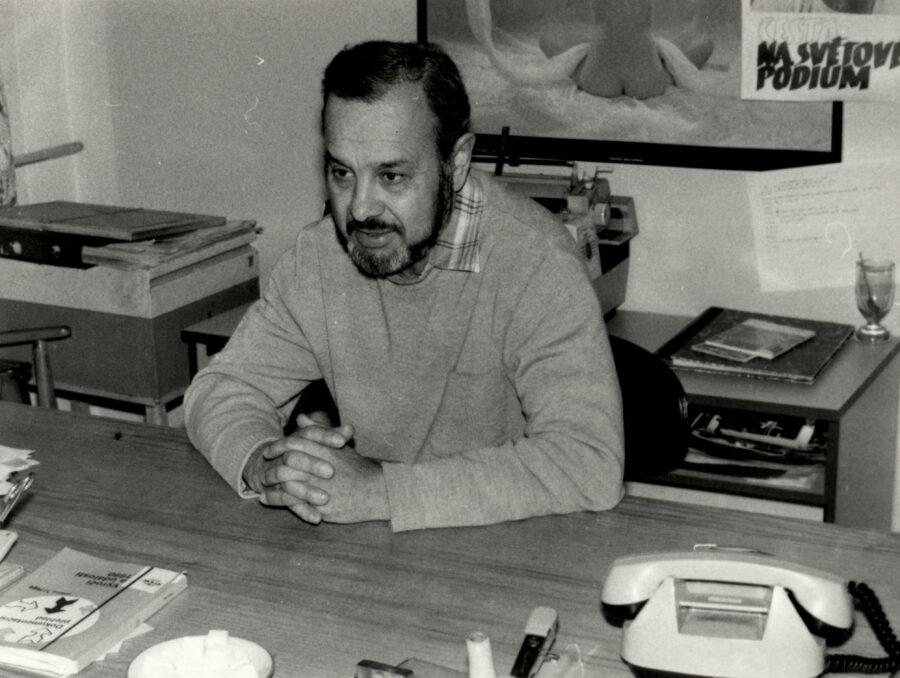

Ing. Karel Holomek (1937–2023)

On 27 August, Karel Holomek, the founder of the Museum of Romani Culture, passed away. He was born into a family of indigenous Moravian Roma who had been settled in Moravia since the end of the 17th century. His great-grandfather Tomáš tried to settle in the village of Svatobořice starting in the 1840s, but the locals were not interested in “gypsies” living there and always chased them away by using violence.

Over the course of the next four decades, the Holomek family never gave up on their dream of settling, and the locals allowed them to set down roots outside the limits of the municipality in “no-man’s-land”, i.e., a parcel of land that was not claimed by the village, nor by the neighboring town of Kyjov. That settlement, which later began to expand, was called “Hraničky” (The Little Borderland) for that reason. Tomáš Holomek’s grandson of the same name was the father of our Karel – JUDr. Tomáš Holomek (1911–1988) and would become the first college graduate in Czechoslovakia of Romani origin, entering Charles University’s Faculty of Law to study in 1932; his studies were interrupted by the war, which decimated his family because of their race, but he survived and worked as a lawyer after the war.

Karel followed in his father’s footsteps, graduating from university in Brno in the field of mechanical engineering at the Military Academy and working there several years as an assistant professor and budding scientist. However, that all abruptly changed when he openly expressed his opinion that the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops was nothing but naked aggression. He was excluded from the faculty. He worked in the first official Romani organization in the Czech lands, the Union of Gypsies/Roma (Svaz Cikánů-Romů), which owned a production facility called Nevodrom (New Way), where he worked as the director of the Brno plant. In one year he built a blacksmithing workshop and began training several Romani apprentices in that craft.

He eventually had to leave that position on the orders of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia’s Regional Committee, however. For the next 20 years, that position remained the only skilled job he performed after leaving the Army. He was only allowed to work in manual labor professions after that, and even those jobs could only be found with great difficulty thanks to the permanent efforts of the “comrades” to ostracize him. Ultimately he was allowed to become a heavy goods vehicle driver, and later, as an engineer, he was relegated to the role of a worker on various socialist construction sites, which were frequently located at a great distance from his home. These included the Ivančice Silo, and he also laid the foundations for the construction of the Dukovany Nuclear Power Plant, worked on the oil pipeline from Šlapákov to Neratovice, worked in chemical factories for a service called Demolition Litvínov, and also worked on several smaller-scale sites such as the fishpond in Ivančice, the railway siding in Ivančice, the railway trans-shipment point at Pávov u Jihlavy, etc.

In 1977 he became a dissident. He was assigned to the network of those distributing banned literature, which he received from Jiřina Šiklová, Milan Šimečka, and sometimes even directly from the vans bringing publications across the Austrian or German borders. The publications he distributed were Svědectví, Listy, Index and mainly samizdat. He also established his own press for samizdat literature.

After the 1989 Velvet Revolution, he became a lawmaker in the Czech National Council for Civic Forum, (Občanské fórum). In 1991 he was the main actor behind the inception of the Museum of Romani Culture, a nonprofit organization at the time, under the rubric of the Society of the Friends of the Museum of Romani Culture Experts (Společnosti přátel o odborníků MRK), of which he was the honorary chair for many years, and of the nonprofit organization called the Society of Roma in Moravia (Společenství Romů na Moravě / Romano Jekhetaniben pre Morava), which provided legal and social work counseling and field programs in Romani localities, and in 1999 he began to publish the Romani-Czech biweekly newspaper through that organization, Romano Hangos / Romský hlas [The Romani Voice].

He was given many important awards, including the Medal of Merit by Czech President Václav Havel (2002), the Prix Iréne (2007), the Roma Spirit Award in the Individual category (2010), the Museum of Romani Culture Award (2011) for his many years of tireless work to benefit ethnic Roma and for the important role he played in establishing and building the museum, and the Ferdinand Dobrotivý Award from Karel Schwarzenberg (2014). In 2005, the director of the Brno studio of public broadcaster Czech Television, Karel Fuksa, made a documentary about him for the cycle called “Portraits”, entitled “Ing. Karel Holomek, Defender of the Weak”. In 2017, the first documentary about a person of Romani nationality in the cycle called “Gallery of the Elite of the Nation” was made about him, directed by Břetislav Rychlík.

He wrote a book about his childhood and the fate of the Holomek family in 2010 under the pseudonym Karel Oswald, called Faraway Memories: Such Beautiful Futility [Dávné vzpomínky. Marnost nad marnost, ale jak krásná…]. However, above all else he was a commentator who published his contributions and essays in the newspapers, especially in Lidové noviny most recently. In September 2017, after a severe stroke, he was paralyzed and bedridden, no longer participating in public life until he passed away.

The funeral for him was held in Brno at the Crematorium on 1 September and was attended by many people from all over the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Eulogies were heard from the actor, director, documentary filmmaker, screenwriter and university educator Břetislav Rychlík and from the author Martin Milan Šimečka. He will have a memorial at the Holomek family tomb in Brno’s Central Cemetery and a mass will be said for him in Prague in October. His ashes, according to his wishes, will be scattered on the peak of Kralický Sněžník Mountain exactly one year after his death. We will be glad if everybody who loved him would join us on that occasion, he would appreciate a cheerful “happening” there. The video recording of the funeral can be watched on Romea.cz.

My Dad, the little (great) man

My Dad was christened Oswald and used that as his pseudonym, publishing Faraway Memories: Such Beautiful Futility [Dávné vzpomínky. Marnost nad marnost, ale jak krásná…] under the pseudonym Karel Oswald. However, he was also called Aladin (I used to imagine him riding on a magic carpet as a little boy, which was one of the stories he used to tell), or Ali, which was his Scout name, probably because of his Oriental appearance. When we were children, my sister and I called him Tatar, because he had black, curly hair and a full black beard, like a Tatar, or just “tata” (Dad), in the Moravian way, never “táta“, because that seemed embarrassing to him. He was always rather mercurial, he responded to everything and very often rolled his wide-open black eyes in his “Holomkovian” fashion – he was simply a Tatar. In his youth he was a Scout who, as a boy, completed absolutely all of those hard challenges with consistency (not speaking for a whole day, not eating for a whole day, etc.), and he was also a gifted athlete who represented the republic of Czechoslovakia in gymnastics.

He was also an incredibly excellent driver (who, by the way, also taught at a driving school), and when we drove to the mountains he would show us “how to skid in real life” on the ice, so I was frequently afraid to be in the car. He was also an inveterate lover of history, especially the history of the Czech lands, he loved heraldry, collected old weapons, and drove us to all the known and unknown cultural heritage sites in what was then Czechoslovakia. You can’t outsmart genes and upbringing, though. I don’t have my father’s brilliance as a mechanical engineer, or his sense of direction, or his gift for languages, but his influence deeply instilled me with a love of art, culture and history, as well as an inclination to approach all of that with full commitment and an open mind, as he loved to say. Some of those who scoffed at him called him a “loose cannon” on that account, and there are different ways to interpret all of this. Today I know he was a pure person with an enormous understanding in particular for all those who were disabled, overlooked and weak. He was a little, great man… He wasn’t just small in terms of physicality, but had the enchanted soul of a little boy even as an old man. That may be one reason people loved him so much.

His daughter, Jana