Lety after the Romani genocide, Part One: Local authorities wanted to build another camp there for Roma after the war

The municipality of Lety in South Bohemia is a locality that has played an important role in the history of Czech-Romani society and interethnic coexistence. Few people today can be said to be absolutely unaware of what happened in the vicinity of that location during the Second World War, as the dissemination of awareness about the camp there had a significant impact on the 1990s.

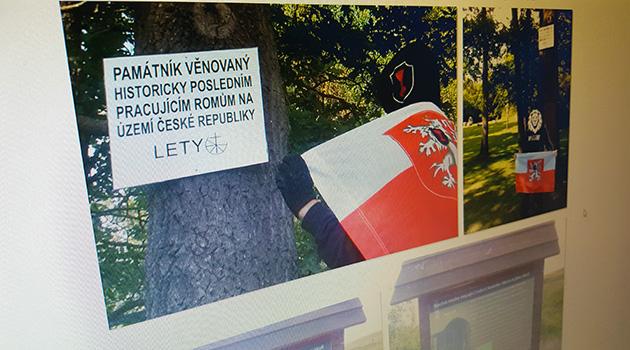

The broader public was introduced to basic information about the creation and operation of the so-called “Gypsy Camp”, testimonies of camp survivors and their loved ones were publicized, and new publications were released – in addition to historical work by academics, popular education works bordering on agitprop demonstrated what the further development of the site had involved, in a clumsy albeit sincere attempt to draw attention to its desecration by the existence of an industrial pig farm there. Over the last decade, the pressure exerted by academics, activists and the relatives of those imprisoned at Lety intensified, and on 21 August 2017 a breakthrough moment arrived – the Government of the Czech Republic, through Resolution No. 609/17, approved the purchase of the industrial pig farm where, in the years to come, a memorial is to be created to the Holocaust victims of Romani origin who died there.

What was it like after the war there before the farm was built? How did society treat the victims of persecution who were returning home from the concentration camps with their hopes?

How have Romani people themselves contributed to being actively involved in dealing with this place? This article is the first in a series that will review the postwar period of Czech-Romani society and thereby the history of the site of the camp at Lety u Písku.

Trials of the former commander and guards of the “Gypsy Camp” at Lety

The racial basis of the annihilation of the Romani people that had just been perpetrated was not acknowledged in the immediate aftermath of the war, and for that reason the state would probably have never have undertaken, as part of the so-called “national purge” at that time, any trials of the guards from the so-called “Gypsy Camps” at either Hodonín u Kunštátu or Lety u Písku if it were not for head guard František Kánský, a former guard from the Lety camp who wrote a shocking testimony about conditions in the camp under the command of Josef Janovský. On the basis of this protocol authored by Kánský, Janovský was arrested on 4 September 1945.

During the course of his three-year trial, of course, the eyewitnesses changed their testimonies, including the “informer” Kánský, who ceased to depict Janovský as a brutal commander. During the trial just two former prisoners were questioned, one of whom had been at Lety when it was still called a “disciplinary camp”.

On 9 September 1948, Janovský was eventually acquitted by the “people’s court” and later began to work for the police services in Prague. Another two guards were dealt with similarly, although other camp survivors – who never testified in court – described them of having treated prisoners with extraordinary brutality as well.

The guard Josef Hejduk was acquitted, while the guard Josef Luňáček was given a reprimand. When handing down the verdicts, the judges referred in their explanation to what they asserted was a necessity for the guards to take a harsher approach toward what they termed “asocial elements”, as well as the guards’ attempt at preventing infectious diseases from spreading beyond the camp itself.

Coming home…

After the close of the Second World War, concentration camp survivors began to return to their former homes. Of the overall number of 6 500 Romani people in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia who were listed in an “inventory” in 1942, a total of 583 Romani people returned to Czechoslovakia after the war.

A few Romani people who survived the war in “freedom”, thanks to their friends or relatives by marriage from the majority society, are also documented as surviving, but the number of others who escaped deportation and managed to hide in the Czech borderlands or in the forests of the Slovak State remains undiscovered. The former Lety camp was covered with lime after the war, out of concern that contagious disease might spread from there and, as research has demonstrated, it was burned to the ground – the most recent archaeological discoveries there tell us that at a minimum, part of the burned remains of the camp were also removed to a location that has been considered to have been the camp’s burial ground.

The families of former prisoners and the survivors themselves felt a natural need to visit the sites where they had lost their loved ones such as the improvised burial ground in the forest near the camp and the cemetery in the nearby village of Mirovice, where the camp administrators had buried those who died in the camp, especially before the typhus outbreak there. Even though no official remembrance site was established at Lety in the immediate aftermath, a wooden cross with a crown of thorns was erected at the site of the former burial ground and is most likely to have been designed and erected by Romani people themselves, both the bereaved and the survivors who had been imprisoned there.

The demonstrable existence of that cross is captured in a short film by Miroslav Bárta, “Don’t Forget About That Little Girl“, made in1959, in which the cross can be seen, although the film does not explicitly describe where it is located (see below). In addition to their broken health and traumas arising from their horrible experiences and the loss of their relatives, the returning Romani people also had to grapple with their not very friendly reception by local inhabitants.

VIDEO

The dwellings and entire settlements on the outskirts of municipalities that the Romani people had been forced to abandon during the war due to their deportation were now found to have been either destroyed or absolutely razed to the ground, while any movable assets salvaged from them had already been sold off in public auctions. There were few unoccupied homesteads available for residency and few work opportunities.

The majority population began to be concerned that “so many Gypsies” would grow in number, and in the summer of 1945 the National Committees of several municipalities in the Slovácko area of southern Moravia sent a petition to the Regional National Committee in Brno in which, out of their concerns over these “unimproved, work-shy Gypsies”, they proposed concentrating the Romani population in the border regions. At the same time we can trace the first migration wave by Romani manual laborers from Slovakia into Bohemia and Moravia after the war – the position of Romani people during the course of the war had not been very favorable in the Slovak State either.

Along with the laborers, entire families arrived in the Czech lands in hopes of finding a more acceptable place to live. These people did not always encounter acceptance – rather the opposite was true.

Proposal for a maximum-security disciplinary center and another “inventory”

A setup that was negative for Romani people was manifesting locally and was also reflected, to a different degree, at the level of the state apparatus. In the correspondence between the Interior Ministry and the Social Affairs Ministry from the year 1946 a proposal appears to apply a regulation that would make it possible for municipalities to ban entry onto their territories by “gypsies and travelling families.”

That provision was based on Act 117 of the year 1927, “on wandering Gypsies”, which had served, among other things, as the basis for the “inventory” that was later compiled of Romani people and for their subsequent deportations. A state proposal to “appropriately emplace the adult members of gypsy families” appears in 1946 as well.

The idea of setting up a criminal education center for that purpose caught on with the District National Committee in Písek, and on 5 November 1946 that committee sent a letter to the Interior Ministry requesting permission to set up such a disciplinary center in Cerhonice (about 15 km away from Lety municipality) to serve the region. A detailed description of the planned accommodation conditions there, with a capacity of 400 beds, includes guards and extensive opportunities to exploit the inmates’ labor, including in the nearby municipality of Mirovice (where some prisoners from the camp at Lety, mostly children, had been buried during the war).

The municipality of Cerhonice objected to the proposal, so the establishment of a “camp” or prison, as the planned center is described in some documents, was never implemented. Moreover, as was stated in the answers sent to the District National Committee from the Interior Ministry, “there is no legal basis for the concentration of gypsies in centers under guard and discrimination against gypsies on a racial basis would not be possible for constitutional reasons.”

It is also necessary to add that, at the same time as these tendencies to concentrate Romani people in one place and guard them with the aim of containing criminal activity were being envisioned, some returning Romani people were also managing to re-establish their positive interwar integration into the majority society and even stopped being considered Romani by local authorities altogether. For example, the Romani law student Tomáš Holomek, after his return home from a wartime state of illegality, resumed his interrupted university studies and graduated in 1946.

However, at the same time Act 117/1927 was still in force, facilitating the creation of official records about Romani people specifically or even the renewal of the pre-existing ones. In August 1947 a count of “all wandering gypsies and other vagabonds avoiding work” (including so-called “světští” or circus people) was undertaken that was not meant to include “properly” living, settled Romani people.

The total number of people so registered at that time exceeded 100 000 for Czechoslovakia as a whole (immediately after the war there were approximately 70 000 Romani people in Slovakia), of whom more than 16 000 were living in Bohemia and Moravia, while a total of just 214 “asocials” had been registered by authorities in Bohemia and Moravia, to the surprise of all. In 1950 a change was made to the legal position of Romani people when the discriminatory Act 117/1927 was abolished and they were formally given the same rights under the law as the rest of the population.

Letters to the President

In addition to repressive attempts to deal somehow with a partially-migrating Romani population that was, in many places, viewed adversely by local residents, we are able to document active attempts at self-organization by Romani people themselves. For example, in 1948 there was a “meeting by representatives of Slovak Gypsies” in Slovakia that adopted a resolution to establish an Association and a memorandum (which seems to indicate the existence of previous such initiatives by active Roma, although no tangible sources about them have been preserved).

In April 1949 the Office of the President of the Czechoslovak Republic received a letter from Jozef Šándor, a man of Slovak Romani origin who had been registered in the previous “inventory” and who introduced himself to the authorities as one of the “model Roma” while defending the necessity for the function of a social officer for the gypsies of Brno, a position he held at the time. The local authorities who were asked for their opinion on the issue by the Office of the President unequivocally supported him.

Šándor, of course, was not an isolated case, as we have documented several such letters with different requests addressed “to Prague Castle”, for example, to appear in Parliament about this or that issue. The active approach by Romani people was, at that point in time, a welcomed element because it aided with the successful assimilation of the Romani population.

The authorities directly called for the involvement of local representatives of Romani communities and offered to collaborate with them. During the 1950s, different trainings of “gypsy activists” were organized to support work “among the gypsy population”, and from those efforts, of course, were recruited the figures who in later years would criticize central policy vis-a-vis Romani people (e.g., Milena Hübschmannová, Gustáv Karika, Elena Lacková).

End of Part One.

Sources used:

Nečas, Ctibor. Holocaust českých Romů. Prostor. 1999

Pařízková, Jindra. Památka obětem romského holocaustu- Internační tábor Lety u Písku a jeho poválečná historie. Univerzita Karlova. 2007

Pavelčíková, Nina. Romové v českých zemích v letech 1945-1989. Úřad dokumentace a vyšetřování zločinů komunismu. 2004

Sadílková, Helena. Slačka, Dušan. Závodská, Milada. Aby bylo s námi počítáno. Muezum romské kultury. Brno. 2018

Slačka, Dušan. „Cikánská otázka“ na Hodonínsku v letech 1945–1973. Magisterská diplomová práce. Masarykova univerzita v Brně. 2015