Ladislav Samek: It is hard to get rid of the label of "institutionalized child" in Czech society

When he was born, he was sent straight from the delivery room to a neonatal institution in Sokolov and then into the care of foster parents with whom he spent the first nine years of his life. Today Ladislav Samek is studying social work and leading an organization in Pardubice called “Children in Action” (Děti v akci) that endeavors to provide long-term support to children in institutional care with their athletic activities and other hobbies.

“I established the organization with my colleagues because we want to change things,” the 21-year-old tells Romano vod’i magazine, adding that he considers it to be an advantage that the issue of children’s homes and institutional care is something he can assess from both sides of the story, as somebody who grew up in such care and as somebody now on the outside. He has never met his biological parents and experienced six different institutional facilities, including a diagnostic institute and a treatment facility where he was placed after committing self-harm as a child.

For the first nine years of his life, Samek did not grow up in a loving environment and his time with his foster family was not easy. “I don’t like remembering it and today I look back on that time as complicated, because the foster family did not function as it should have. We, the children whom they took care of for so many years, had no outlet for our feelings, there was nobody in whom we could confide,” he says.

His foster family had four other Romani children in their care, who came to them from a children’s home, and they were also raising their own biological daughter. “After school we had to follow a strict regime of the kind that I never experienced anywhere else, not even in the children’s home or the diagnostic institution where I spent time briefly after I was removed from foster care. When class was over we had to immediately take the first bus home and if we were late were punished right away, or given more duties to fulfill. It wasn’t until later that we started to find out that other children had absolutely different family experiences and had never encountered any such treatment,” he describes his childhood.

“I never discussed it with anybody because I believe it wouldn’t have helped to do so. Unfortunately, there are some things a person has to reconcile themselves to being unable to influence, and this was one of them. During puberty my foster parents couldn’t deal with me anymore, so they got rid of me and I ended up in a children’s home. After me, then my other ‘siblings’ were institutionalized, because reports of neglect began to be made about those foster parents,” Samek explains.

He established Children in Action two years ago. He is collaborating with several dozen children’s homes and organizing charity and sports proejcts for children and teenagers growing up in such facilities.

Looking for talent

“We organize the nationwide competition ‘Talent Search’ for the fourth year in a row, which gives an opportunity to the children from children’s homes to demonstrate their gifts. More than 200 children applied last year. Some dance, play musical instruments, sing, or choreograph numbers full of gymnastic elements,” he describes the contest.

Samek considers support for the development of children’s personalities and skills to be important. It is not always possible for children from children’s homes in particular to attend enrichment activities after school.

“I went through a similar experience myself. When, at the age of 15, I told my tutor that I’d like to go to an afterschool program, he said: ‘Hey, if I pay for you to go to such a program, then another 40 children will come to me saying they want to do that too, and I simply can’t afford it.’ For that reason we’re doing our best, thanks to our projects, to support specific children in their development,” he explains.

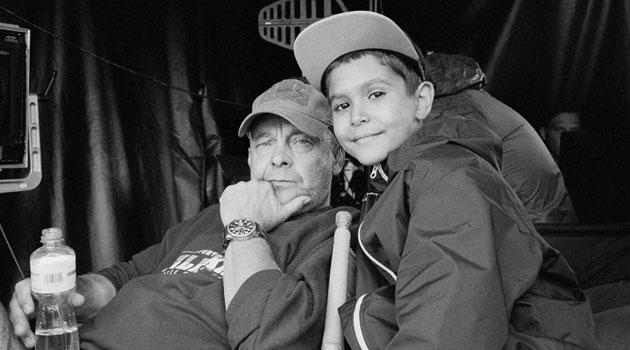

“We’re supporting a little girl, for example, who just now qualified for the Czech national championship in gymnastics. There’s an eight-year-old boy who is an excellent freerunner, he set up his own group and he goes to parkour camps,” Samek brags.

“Joining a sports club, for example, where they make new friends and get to know a different environment, can influence them positively. It seems important to me that the children do something they enjoy and that they have the experience of progressing in something,” he says.

Remaining online

During the pandemic, Children in Action also focused on helping children access instruction online. They used an online service to organize assistance for educators tutoring children in institutional care.

A total of 200 volunteers signed up, not just educators, but also nurses or high school and college students. “We also brought the children computers and tablets so they could participate in distance learning. Unfortunately, these children had been somewhat forgotten about. Most public collections and individual donors provided most of their donated technology to the socially vulnerable, or to single mothers who couldn’t afford to buy such technology. The problem was a much deeper one, though. Ultimately it was big companies from Prague and Brno, individual donors, and the well-known figures who are our patrons and with whom we have long collaborated who helped us out. It was necessary not just to provide aid to the children’s homes, but also to the nursery facilities, diagnostic institutions and juvenile reform homes,” he describes the lockdown time, when schools were closed.

In addition to computers, Children in Action also distributed personal protective equipment to the children’s homes during the pandemic. Their patrons are also involved in the organization’s other projects.

During the Christmas holidays the group helped give more than 300 children in children’s homes across the Czech Republic Christmas gifts. The money was raised by auctioning off dozens of uniforms worn by top Czech athletes, mostly football players and hockey players who are also the organization’s patrons and regularly participate in charity work.

All of the organization’s projects are financed purely from sponsorship gifts. “We established the organization with the idea that we don’t want any subsidies from the state or the EU. Everything that we do can be seen in the transparent account, with financing from people who are also putting their heart into it. They regularly come with us to events at the children’s homes, some have already begun to organize the events themselves because they see it makes sense,” he says.

Not just Romani children in care

Thanks to their collaborations with children’s homes, Children in Action is also doing its best to break down some of the engrained prejudices and stereotypes that are so closely associated with institutional care. “Many people have the idea that it’s just Romani children living in children’s homes. It’s not like that, though. I’d say its balanced. Naturally it differs from region to region – it will be different, for example, in the Ústecký Region than it is in the Pardubice Region,” he explains, adding that it is necessary to assess each facility on its own terms, because each one will be different.

“Society is not informed, that’s the basic problem. That’s a big task, not just for us, but for these facilities themselves. The ideas about how things operate in these institutions are frequently distorted and stereotypical. People still have a lot of prejudices,” Samek says.

“When I went to high school, one teacher told the entire class that I was living in a children’s home. You should have seen, at that moment, how my classmates distanced themselves from me. On the one hand they don’t know you, they know nothing about you at all, but all you have to do is wave the label of ‘institutionalized child’ and it’s immediately bad. That is damaging all of the children who are living in institutions, to an unreal extent. That’s why I’m doing my best to do as much outreach as I can, to inform people, and to help children who are not at all to blame for the fact that their biological families didn’t function like they ought to have,” he explains.

Support for biological families is important

In practice, however, Samek says support for biological families whose children have been taken away on the basis of their unfavorable socioeconomic situations is lacking in the Czech Republic. “Personally speaking, I have never encountered Romani children in care who have been abused or mistreated. The reasons [for their institutionalization] were actually socioeconomic. That, in my view, sends a clear message, and it’s also another task for the state, to reflect on the reasons for removing children from their families. If 10 people are living in one room, that is not a standard situaiton, but is it genuinely a reason to remove children from their biological parents? The state should prepare support for these families in such cases so the children could remain with them,” he emphasizes.

Samek has long advocated the closure of neonatal institutions. “The Czech Republic is one of the few countries where neonatal institutions still operate. That is an enormous embarrassment! We put newborns into institutions, and unfortunately, our government representatives see nothing wrong with that. During all the time that the existence of neonatal insitutions has been brought to their attention, they have been unable to invent and legislate a different system. They could get some inspiration from other parts of the world where it’s already been working for some time without such care,” he laments.

According to Samek, the first three years of a child’s life are the most important to the child’s further development. “I would prefer newborns be temporarily placed with foster parents instead of with neonatal institutions. They could care for them for those first three years, if they are not adopted before then. Another option would be to open children’s centers where children are able to grow up in a community without being raised together in a group of 20,” he proposes, adding “I know that’s also not ideal, but if their own parents are dysfunctional or unable to care for the child, there is no other option for the time being.”

First published in Romano voďi magazine.