Interview with activist Miroslav Brož: Integration policy for Roma is failing in the Czech Republic, they are discriminated against and victimized by systemic racism

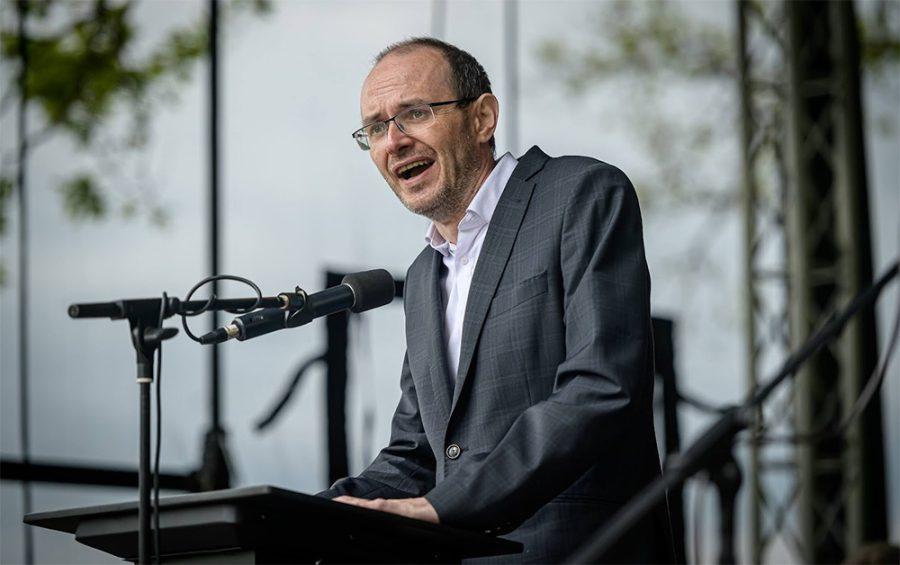

Miroslav Brož, an activist and advocate for the human rights of Romani people, recently spoke at the commemorative ceremony in Lety u Písku with a very critical speech warning that the Czech integration policy for Romani people is failing. Brož, the founder of the Konexe nonprofit organization, asserts that systemic racism and unaddressed discrimination in all areas of life is the main reason for this failure.

In an interview for news server Romea.cz, Brož expresses his view of the current situation of Romani communities, criticizes Czech integration policy, and explains his critical speech at the commemorative ceremony. Here is his perspective on why the “Emperor of Integration” has no clothes and what has to change for real inclusion to happen.

Q: This year during the commemorative ceremony at Lety you gave a critical speech in which you said the integration policy for Romani people in the Czech Republic is failing. You compared the situation to the fairytale “The Emperor’s New Clothes”, where everybody knows the Emperor has no clothes, but is afraid to speak about it. What led you to that conclusion?

A; I was afraid the other speakers would not be critical, or that they might even be celebratory, that they might mention the horrible things done to Romani people in the past in the Czech lands without also mentioning the horrible things happening to Romani people in the Czech Republic today, the current situation of Romani communities, that they would lack the courage to do so, that we would pretend the Emperor has new clothes, in other words. I was doing my best to give voice to the ordinary Romani men and women who are never asked their opinions about anything and never get the opportunity to speak in front of politicians and TV cameras. I know that Romani men and women liked my speech, they identified with what I said. At Lety many of those present came up to shake my hand and thank me and many people called or wrote to me afterward. I thank them very much, I really appreciate it.

It was not the first critical speech I had ever given at Lety, I have been attending regularly for 14 years and if I’m not mistaken I’ve given six or seven such critical speeches during that time. This year’s speech drew attention because there were high-ranking politicians and many journalists there.

Q: We don’t hear such sharp criticism of the integration of Romani people in the Czech Republic very often here.

A: I crossed a certain “red line” with that speech. It’s a taboo to publicly speak of the Czech integration policy for Roma as a failure, to describe the real state of affairs, to say nothing of doing so in front of high-ranking politicians. The custom is to speak of successes and examples of good practice, to praise cooperation with the Agency [for Social Inclusion] and such. Among the people working in the field of integrating Roma, unfortunately, there is a kind of unwritten solidarity, in the sense that we’re all in the same boat, so if we criticize things it will disrupt the flow of financing, we’ll lose our jobs, let’s be glad for what we have. Self-censorship predominates, the picture is painted as being rosier than it is. All one has to do is look at the website of the Agency for Social Inclusion – one could easily get the impression that the integration of Romani people is succeeding in the Czech Republic from what is posted there, one success after another, all of it accompanied by stock photos of models. It’s comical. The reality is totally different. Does anybody believe what is being described? Let’s stop pretending. The Emperor has no clothes.

Q: Why, in your view, is this not working?

A: Because the actual cause of most of the problems faced by Romani people in the Czech Republic is systemic racism and unaddressed discrimination in all areas of life. We mainly have and mainly support organizations in the Czech Republic which provide Romani people with social services that do not yield any positive change, because they just deal with consequences and don’t know how to work with the causes of the current state of affairs. On the other hand, there is almost a total lack of organizations and programs targeting the causes of the current situation for Romani people, and the few that do exist are not supported, organizations which would concentration on combating discrimination, activating Romani communities, educating Romani people, emancipating them, which could finally start some change. There are many levels to this. At the local level it is the case that the nonprofit organizations which are meant to aid Romani people have totally lost their natural role, which in countries with a more developed level of democracy is the watchdog role. If something wrong is going on, the watchdog barks loudly, stirs things up, and also bites if necessary. What usually happens is that a small nonprofit in a town somewhere in the north has to first keep up good relations with the local politicians and the authorities who influence which NGO receives financial support for its work. If a little NGO is critical, if it “barks”, or if attempts to “bite”, that basically means it will close, we know such cases… “don’t bite the hand that feeds you”. Small NGOs very often have become fig leaves and a welcome alibi for the authorities instead of watchdogs – for a politician, it is nice to be able to say that the local Romani ghetto is being addressed in their town, if journalists ask about it, the politician can answer that they have good cooperation with the NGO or with the Agency. The fact that the situation in that Romani ghetto in that small town has been constantly deteriorating over the last 20 years, despite the invested resources, is something in which nobody takes much of an interest. Years ago, an approach was advocated for here toward Roma by social services which experts call an ethnic blind approach. Those who deliver this approach are the big chain nonprofits and the Agency above all, which was established by the Government. It consists of approaching clients in such a way as to ignore their culture and ethnicity, approaching everybody the same, whether they be Romani, Ukrainian or Martian. A staffer who aids Romani people allegedly does not have to be an expert on their customs or their culture, it’s enough to be an expert on unemployment, education, etc. According to this approach, it is basically useless to learn the Romani language, or to try to understand the rules by which a Romani community functions. That sounds fine, but it really does not work at all in practice. To begin with, antigypsyism and the discrimination on an ethnic basis that it produces is the root cause of many of the problems Romani people face. Individualized social work based on the “ethnic blind” principle and so forth is the customary approach taken by social services in the Czech Republic, and it does not involve any instruments or offer any solutions for how to make progress with that situation. It does not address the causes, it does not know how to work with the subjects of discrimination, structural racism, or systemic racism, but just attempts to address the consequences of those phenomena.

Q: Can you be more specific?

A: Let’s imagine, for example, a young Romani family – the man works, the lady of the house is on maternity leave with two young children. If such a family were not Romani, they would rent a normal apartment on a housing estate for a relatively low price, they would have a nursery school and a primary school around the corner, they would have a nice playground across the street from where they live. Their children would walk to the local primary school, then they’d go to some kind of secondary school, and they might even go to college or university. However, because the family is Romani, they have no chance to rent regular housing, because the discrimination against them is so strong, so they have to go live in a ghetto, where they rent a smaller, worse apartment from one of the “traffickers in poverty”, one without a proper bathroom, and they pay a higher rent than normal for it, which destroys their budget. In addition, somebody is selling drugs on the floor above them, there are injection needles left behind in the corridor, and there are bedbugs in the entire building. Instead of a playground, there is a garbage dump out back, and the only school in the neighborhood is attended only by Romani pupils, it is segregated – so the environment overall is one of high risk. Their lives will develop in an absolutely different way just because they are Romani, the environment will grind them to pieces. To pretend that I don’t see this, to ignore the causes, to never attempt to address and eliminate the causes, but instead to visit this family in the ghetto in order to aid them with filling out different forms, to check on how they are raising their children in this neighborhood of garbage dumps, to professionally advise them on how to manage their money, or what the best spray to use against bedbugs is – can that really be the change and the solution they need?

Q: In your view, then, social work in Romani socially excluded localities is not working correctly?

The term “social worker”, in some impoverished Romani communities, is almost as bad of a curse word as the term “collections agent”. This is closely connected to the question of whether people are using social services or social work on a voluntary basis. The most important, main principle of social work is that it be on a voluntary basis. In the Czech Republic, unfortunately, this is frequently neither respected nor upheld, social work is perceived and used by municipalities and other institutions as an instrument for disciplining impoverished people. If we have a residential hotel that is troublesome, we send social workers to map the situation and arrange for some order there. According to the applicable social work standards, the relationship between a client and a social worker is meant to be established on a basis of mutual respect and trust. The word “mutual” is important here. How many social workers have respect for and trust their impoverished Romani clients? The phenomenon in recent years of the crisis in Romani-related social work has been intensifying, where the subject of the forced collaboration of impoverished Romani people with social workers is coming up as an outcome of what are called “social activation services” (SAS) for families with minor children, where nonprofits work together with child welfare departments. Before that system was created, if a family had problems raising a child – for example, the child was smoking grass, or stole something from a supermarket, or was truant – or if it was suspected that a young mother wasn’t able to take good care of an infant, those were the classic examples of social work clients, and so the family was supervised by what people call “social welfare” (child protective services – OSPOD) and an OSPOD social worker began regularly visiting the family to monitor them. If the family did not improve, if the social worker was not satisfied with their cooperation, if the deficiencies could not be eliminated, then OSPOD filed a motion with the court and the child would be taken into institutional care. However, the current system involves such work in the field with the family, the monitoring activity, having been taken over from OSPOD, for the most part, by some nonprofits. OSPOD assigns their staffers to families who are under supervision and who are meant to cooperate with the nonprofit staffers on improving the situation with the care and raising of the child. Each and every nonprofit staffer performing social activation services in collaboration with OSPOD ends up in a situation of difficult dilemmas, ethically speaking, because there’s a clash of loyalties between their loyalty to the best interests of the client, to the best interests of their own organization, and to OSPOD. They lose their independence. They have to write up reports about the client family for OSPOD on a regular basis, and the content of those reports determines the fate of the family, and that comes into conflict with another principle of social work, which is that the relationship between a client and a social worker should not involve a power dynamic. Naturally, it is the provision of this special type of social service that negatively impacts the work of the organization that is participating. They must maintain a good relationship with OSPOD at all costs, otherwise OSPOD will stop the collaboration and the nonprofit will lose its financing and will have to let people go. It will be difficult for such a nonprofit to protect its clients’ rights if the municipal social welfare department violates them.

Q: What about the community work that is currently starting to be advocated for and developed in the Czech Republic?

A: The Czech Republic is specific in that community social work in relation to Romani communities started to be implemented and supported very late, at a time when similar programs have already been running for a long time in other European countries. In my opinion, that was caused by the fact that the big providers of such services were resistant to this kind of work and for a long time they managed to influence the distribution of financial resources in such a way as to direct them toward integration programs based on individualized social work and networking institutions that were not under the management of Romani people. Later, when avoiding this step was no longer possible, the big players adapted and community work began to be supported in the Czech Republic.

As the Konexe association, we have been working with the community since our inception, basically we were established to do community work. I daresay we really have a lot of experience with it and we know how to do it genuinely well. That is why we are following with such concern how much its principles are currently being distorted and trampled on here in the Czech Republic.

Q: How are community work principles being violated?

A: The basic, main principle of community work is that it is done in the community by a local organization that is part of the community and has strong ties to it. It is organized from the bottom up by people from the community, not from Prague. Anywhere else in the world, if a nonprofit wants to apply for a grant for community work in an impoverished ghetto, they have to demonstrate first and foremost that they are a local organization with ties to the community and that the community trusts them. In the Czech Republic, that condition is not included in applications for community work grants. As a consequence, the chain nonprofits from Prague are performing “community work” somewhere in the ghettos of North Bohemia, because they won the “community work” money, but they have no actual ties to the communities, nor do they have community work know-how. That won’t work, by now it is clear that these resources are being inefficiently spent, yet again. The word “community” has even become fashionable and overused, it is being applied to things that are unrelated to any community. The alleged “community centers” that have appeared in some Romani ghettos are a good example. By now there are dozens of such places with that name, but I believe there are at most five genuine, real community centers in this country.

Q: How does this work abroad?

A: If you want to establish and register a community center in another country with a community work culture that is already developed, you have to follow certain rules. For example, the character of the center has to be about the community, it can’t be a “community” center in name only. That means the community itself determines the arrangements and the program of the center as a whole. Mostly it works through a board, a management committee that takes basic decisions, there are typically five members on the committee, two represent the nonprofits running the center and three represent the community. That committee has the final word. Similarly, people from the community are involved in the center’s operations on all levels – which doesn’t mean that we hire one Romani woman through the public benefit work program as a cleaning woman, or as an assistant, but that we also hire Roma for the direction and the management of the center. Similarly, the community has the opportunity to contribute, to an essential degree, to the center’s human resources policy, choosing new employees or dismissing those who are unable to incorporate themselves into the community. All of that is absolutely unimaginable here in this country, it contravenes how social services are undertaken here. Romani people are viewed as the objects of integration here, not as discussion partners, to say nothing of partners in planning or seeking solutions. We would never invite the patients to a medical meeting by the management of the insane asylum, right? Such paternalism is simply omnipresent here. The phenomenon that is called the “racism of low expectations” exists here, so even if we non-Roma actually wanted to involve Romani people, we believe they aren’t clever enough or educated enough to understand how we want to aid them, or what we’re planning for them, we believe they wouldn’t know how to discuss it with us.

That belief is then projected into the planning of Romani integration, and that’s bad. In each town where there is an excluded, impoverished Romani locality, there is a planning group in operation. They have different names – the Mayor’s Action Group, the Community Planning Group, or the Local Partnership Group set up by the Agency for Social Inclusion. However, it’s always the same, the people in charge of integrating Romani people in that town regularly meet to discuss the situation of impoverished Roma and seek solutions, they frequently decide how the money designated for aid to the Roma will end up being spent. The problem is that the people about whom these groups are meeting, the people whose futures are being prepared, are not represented in these planning groups. For example, where we live, in the city of Ústí nad Labem, a so-called “community planning” group has been meeting for probably 20 years now attempting, unsuccessfully, to address the situation in Předlice and other Romani ghettos. The name of the group is confusing – while it has the word “community” in it, no community members participate. Representatives of municipal institutions and nonprofits meet in that group, and during their two-year cycle they spend the first few months elaborating a strategy document, an analysis of the community needs. Naturally, this is absurd, the gadje [non-Roma] are sitting at the table and writing up impoverished Romani people’s needs. The list of needs that results does not correspond to reality and the real needs at all. It regularly turns out that the biggest need of the Roma is for the nonprofits involved in this group to aid them, or rather, to receive enough financing so that they can assist them. After that, a plan is created based on the erroneous analysis of needs, and each nonprofit in the group writes up what it plans to do for the Roma. Money is then distributed for that in the next period. I’d call it “carving up the bear” after it has been successfully hunted.

Q: You’ve mentioned the Agency for Social Inclusion (Agentura pro sociální začleňování – ASZ) more than once in this interview. Martin Šimáček was recently reappointed as its director. What is your opinion of how it operates?

A: I consider the Agency to be the flagship of this bankrupt integration policy. It seems to basically be more of a PR agency to me. I have to admit it is a brilliant, productive one. PR is published for the public about the integration of Romani people succeeding in the Czech Republic, that solutions are on the table, that Agency experts have the answers. Then it implements PR for the municipalities about the necessity and the advantageousness of collaborating with the Agency – if you all cooperate, we will manage to arrange grants for you. Romani people fall by the wayside in all of that. The Agency sometimes even causes harm in some of the localities where it is active because its methods do not reflect the real needs of Romani communities. I recall, for example, one Romani ghetto where football was really popular. Right next to the ghetto there was a low-quality pitch, nothing but sod, but from morning to evening Romani footballers were chasing each other around on it, the local Roma even established their own club and proceeded to win the district championship, which was probably the biggest success of amateur Romani football in the Czech Republic to date. Then the Agency arrives on the scene and brings money to the ghetto, the pitch is beautifully, expensively reconstructed. However, it is also declared too good for the Roma to be flying all around it without supervision, and the keys to the pitch are entrusted to a non-Romani nonprofit, which makes it available to Romani footballers just twice a week for two hours at a time. Even so, subsequently the nonprofit gets a grant to support sports among impoverished Romani people. The activists who are local, the ones who managed to create the team and win the district championship, get no support. That meant the end of football in that place. The money that came through the Agency, in that case, did more harm than good. There are many such cases.

I believe Martin is a fair and a good person, we’ve known each other about 20 years, on a human level I have nothing but positive things to say about him. Professionally, though, he is actually a big nerd for PR. On the ideological level we are polar opposites. He is, to many people, the embodiment of the dominant, dysfunctional, expert, paternalistic approach, a symbol of the prioritizing of support for those big chain nonprofits over grassroots Romani organizations. He opposes participation by Romani people and promotes the ethnic blind approach about which I have already spoken. All one has to do is recall the fight over removing aid for Romani people from the Agency’s original name. I know that Martin has now absolutely reversed himself in some things and begun, for example, to speak of the necessity of involving Romani people. It would be brilliant if Romani people from these localities had meaningful representation on the Agency’s planning groups – and actions speak louder than words. I perceive his reappointment to be an attempt to maintain the current status quo, to arrange for this dysfunctional integration policy to continue, to arrange tenders for the big social service providers for the next budget period, and to delay the necessary reforms. We won’t be able to avoid those, though.

Q: In addition to the Agency for Social Inclusion, which is a department of the Ministry for Regional Development, there are also other public bodies involved with Romani-related subject matter. One of them is the new Department of Social Integration at the Labor and Social Affairs Ministry, led by a past director of the Agency, David Beňák, who is Romani; we also have the new Government Commissioner for Roma Minority Affairs, Lucie Fuková, who is Romani, as well as the Government Council on Roma Minority Affairs, and somewhat also the Government Human Rights Commissioner, Klára Laurenčíková. Are these entities or these figures able to somehow aid with improving the situation for Romani people? What is your opinion of them?

A: Naturally I’m quite glad these positions were established at all, that we even have a Government Human Rights Commissioner and Commissioner for Roma Minority Affairs. I’m also glad that those appointed to those positions do not harbor any anti-Romani biases, they don’t reject the European concept of human rights – which could have happened, let’s recall how Mr. Křeček became the ombudsman here. On the other hand, I don’t absolutely have a good feeling about how this Commissioner for Roma Minority Affairs position is being executed. In countries with more developed democracies, persons are appointed to such positions who become the voice of the community whom they represent, and they are critical, they tell bureaucrats and politicians the unpleasant truths they don’t want to hear – nobody else will serve that role. In Berlin in December 2022 I met with the German Federal Commissioner for the Rights of the Roma and Sinti. He is a gadjo [non-Roma], a sharp lawyer who over many years has given free legal aid to Roma and Sinti all over Germany, bringing lawsuits about their discrimination, assisting them when others wanted to evict them, suing the authorities for violating the rights of Romani people. The Roma themselves chose him because they knew he would stand up for them, that he would immediately speak out against wrongdoing, that when a local case arises, he will come and offer his help, that if he has the feeling that something isn’t in accordance with the law, he will immediately file a lawsuit. I think Czech institutions and politicians are not prepared to have the kind of Commissioner that a democratic, western country has. They wouldn’t stand behind such a thing, they would never voluntarily allow a biting flea of that kind “in their fur”, as it were. The concept and execution of this function is just different, if you look at the Facebook profile of the Commissioner for the Roma in Germany, you won’t find photos of him laughing, you see cases of Romani people’s rights being violated, criticism of the institutions that violate them and so forth. It depends on what we want, if what such a Commissioner is to do is to actively defend the rights of Romani people, be their voice and criticize the deficiencies that exist, or if it is meant to function as a fig leaf and generate alibis and positive PR for the Government and the idea that the situation is being addressed.

As for the Government Council on Romani Minority Affairs, I believe it has not functioned well for a long time. I have never comprehended who chooses its members and according to which criteria. I think it does not manage to raise and resolve the hot topics that are harming impoverished Roma. For all the long years that it has functioned, the results of its work are unknown. I decidedly would not want to make an across-the-board statement about all of its [civil society] members, I know that some of them actually are working or have worked well, they have been doing their best, but such people have never formed the majority [of the civil society members]. I think the criteria for the new [civil society] members to join the Council are that they not be fighters, that they be loyal, and mainly that they never criticize anything out loud from their position as Council members. I could imagine a Council with its own channel for information that would regularly communicate with Romani people several times a week, comprehensibly informing them about what they are working on, during times of crisis speaking up to support them, criticizing the bad things that happen as well as submitting their own proposals for solutions to the Government. That’s not how it works, though, there’s no interest in anything like that. Apparently there will be changes in the next Council, they are looking for new members now, but they have evidently absolutely given up on the idea that the Council should serve as a Romani voice and that the Romani [civil society] members’ role should be to communicate the interests and perspective of Romani communities, because the call for new [civil society] members is looking for experts, professionals. There will probably be an even more narrow tendency towards an anti-grassroots, ethnic blind, professional approach. What is necessary is to head in exactly the opposite direction. As for Mr. Beňák or Ms. Laurenčíková, I don’t have any information at all about their activities, I don’t know their work, so I would prefer not to comment on them.

Q: Your opinions are quite critical. What kind of reaction do you encounter when you express them?

A: If you openly describe the failures of this system, everybody is naturally angry with you, they perceive you as a danger and the repercussions soon follow.

Q: Repercussions?

A: Those follow the rule that if you can’t refute the message, you attack the messenger. I have basically been pushed out of my own field [social work], little by little. I’ve met with quite harsh practices against me, personally. For example, I recall when a highly-placed manager of a chain NGO sent a letter to my superior telling him that if the organization where I was working wanted to maintain its good relations with the chain NGO, then I shouldn’t be working there. Or when I was working for a French employer, a highly-placed manager from the Agency for Social Inclusion – a person with whom I had never met and never even heard of – got a meeting with my superior and convinced him that they should let me go because they alleged I was a drug addict (sic!). These are “kompromat” (compromising material) tactics similar to what the StB [the Czechoslovak communist-era state police] once used. I don’t think I’m the only person with such an experience.

Q: You are working very part-time on a community project of an experimental nature that the ROMEA organization is realizing in the Czech Republic, could you describe it for our readers? What else are you working on besides that?

A: For ROMEA I am coordinating a small, experimental community project in the ghetto of Předlice in Ústí nad Labem, we are activating a local community of neighbors who are Romani to take more interest in the locality’s situation. We meet with them regularly to discuss the situation in Předlice. On the last day of April this year we held a community day, more than 200 visitors came, and the community agreed to attempt to get the city to build a local playground, because one is greatly lacking. This is an international project, it’s not just running in the Czech Republic but also in Bulgaria, Hungary and Spain, we will be exchanging experiences and mutually testing the methods we develop. I do my other activities as a volunteer in my free time. Konexe doesn’t apply for grants, we don’t even have a bank account. I am working on the case of the late Stanislav Tomáš for a second year in a row now, the Romani man who died during or immediately after police intervened against him. I serve as the link between the attorney and his family and I have been gradually aiding the family with solving the broad range of problems they are facing. I also provide expert social counseling to the impoverished Romani people who ask me for it, but I’ve had to limit that now compared to the past, the situation of Romani people coming to my home to ask for assistance (instead of visiting the NGOs) was unsustainable, my neighbors were getting scared and so forth. Well, I also help regularly wherever there is a crisis – that’s basically the point of Konexe, to aid Romani communities during crises and danger. We assist the Romani people who are in absolutely the worst situations. I believe that with my education, my years of practice and my skills I should be working as a social worker trainer somewhere by now, as a methodologist who could prepare social workers to work in Romani communities and lead them, teach them how to work with a community. Years ago I did train several Romani people when I was in one job to become assistants to social services, and when I look back, I consider that to be one of my biggest professional successes, because I know they are doing that work well, in a high-quality way, and they are helping to change the situation in their community. I am not afraid to do any kind of work, though, I also began working for a hospital in what was de facto a manual labor profession, I worked in the COVID-19 ward for 23 months, I was there during the height of the pandemic.