Fedor Gál: It's as if the Roma are wearing the yellow star to this day for us Jews

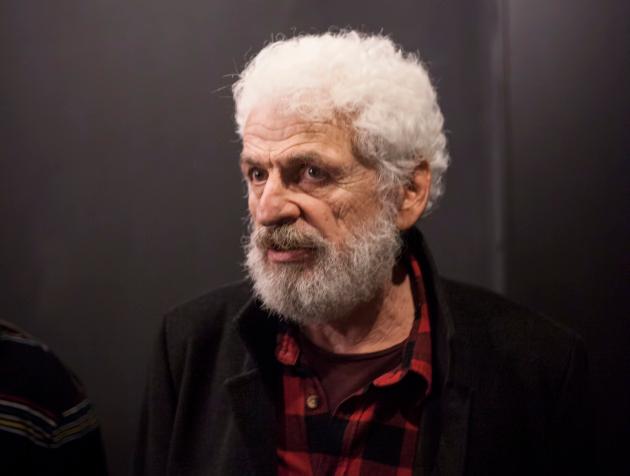

doc. PhDr. FEDOR GÁL, CSc. was born in the concentration camp of Terezín in 1945. He graduated from the Chemistry Technology Faculty of the Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava and has worked for the Sociological Institute of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, the Faculty of Social Sciences at Charles University in Prague, and at the University of Economics in Prague as a sociologist and prognosticator.

Prior to the Velvet Revolution of 1989, Gál was one of the most famous dissidents in Czechoslovakia. He initiated the “Public against Violence” (Verejnosť proti násiliu) movement in Slovakia and chaired it.

Gál was also an adviser to the Federal Government of the Czech and Slovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR). He co-founded the commercial television station TV Nova and in 1995, the GplusG publishing house.

Since 2009 he has dedicated himself to documentary film production (Krátká dlouhá cesta, Dobré ráno Slovensko, and the online project “Natálka”). He regularly publishes his opinions on his blog, www.fedorgal.cz, and in book form (O jinakosti; Vize a iluze; Lidský úděl).

Gál has lived in Prague since 1992. When asked in this interview why he reads the comments in discussions responding to his opinions online, the author, documentary filmmaker, politician, publisher and sociologist says: “I want to know whether, if I walk along the square here, 30 % of the people who pass me by might hit me or want to lynch me once the right conditions arrive for them to do so.”

Q: After the revolution you co-founded the GplusG publishing house, which contributed to books on Romani subject matter beginning to be published here.

A: I was born in a concentration camp and I’m a Jew. I know what the ghetto and barbed wire mean, and I know what it means to not have that elementary feeling of belonging to the majority society. That personal experience of mine, and the experience of my parents and grandparents, has stuck with me my entire life. In other words, when I established the publishing house, I automatically knew I would publish literature that was close to my heart. That means books about the Holocaust, or about abused children. I didn’t want to look for authors in some portfolio, I turned to those whom I knew and trusted. That’s how I got to Markus Pape, to Paul Polansky, to Luboš Zubák, and that’s how I also got to the first books about the Holocaust of the Roma, which I knew nothing about before that. The first book we published was the book about the Holocaust of the Roma at Lety u Písku by Markus Pape, A nikdo vám nebude věřit [And Nobody Will Believe You]. Coincidentally I was just recently at the premiere of the documentary film Lety and also at the book launch for Markus Pape’s new book about Jiří Letov. My interest in this subject has lasted several decades, but I came to it because of my personal attraction. My first contact with the Holocaust of the Roma was shocking, because I hadn’t known anything about it! We’re talking about the beginning of the 1990s.

Q: You have always spoken openly about your Jewish origin and the fate that befell your family. What was your perception of those meetings with Romani eyewitnesses to the Holocaust and their concerns over speaking about it?

A: You know, 91 % of my family perished during the Holocaust. My Mom and her sister survived, nobody else. However, in our family, it was never spoken of. When children in Bratislava began shouting “you kike” at me, I didn’t know what it meant. I didn’t find out that I had been born in Terezín, and that it had been a concentration camp, until I went to school. I have reflected, quite frequently, on why our Mom never spoke of it. My deduction is that the experiences must have been so traumatic that all those people wanted to conceal experiences inside themselves, to bury them, not to speak about them. Their dignity had been extremely humiliated, and they didn’t want to talk about it. If I hadn’t encountered people who had survived Terezín and who did speak about it all, then I would never have known anything, and I was already quite adult by then. If I had never read Arnošt Lustig‘s book on Terezín, then again, I would have known nothing. Mom kept quiet, and so did her sister.

Q: Did you confront your family about that?

A: I confronted them, yes. I was losing sleep over it. I began to research the documentation, to track people down, I began on my own to write the story of our family, which was insanely fragmented. I made a film, I wrote a book, and I believe that exactly this situation applies to Romani people too, because most of them do not want to speak about what they experienced during the Holocaust. I recall how Markus Pape and I put together the testimonies of the Romani survivors of the Holocaust for the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. and for Yale University. We did the very first interview with a gorgeous elderly woman who really reminded me of my Mom. It took a long time to convince her to speak on camera. Eventually we succeeded, but the condition was that she would sit with her back to the camera. That was, for me, such a shock, because this beautiful, brave lady, who had survived horrible things, did not have the courage to show her face even decades after the war – because she did not want further damage to be done either to herself or her children.

Q: How do you explain that?

A: Fear! The Jewish survivors also kept quiet, but books about the Holocaust and Nazism were published immediately after the war. Among the Roma, however, that fear has survived to this day. That, for me, is horrifying. It’s as if the Roma are wearing the yellow star to this day for us Jews. It is a testament to the fact that the Jews were accepted by the majority much faster and to a much greater extent than the Roma. I don’t want to get into the causes now – you can’t recognize a Jewish person on the street by skin color here, because you have to have a special “sixth sense” to distinguish a Jewish person from everybody else by the nose, or the eyes. Romani people here are more visible on the street, and they bear the consequences of that. It is also said that the Jews are “people of the book” and that the Roma are people of verbalization, speaking, music, singing, dance. Thanks to that, among the Jews education traditionally always had a high status, so many of them made it into the intellectual elite. They are attorneys, teachers, scientists, but among Romani people there is a different tradition and a different culture, so they have had a different position in that imaginary ranking of social status than Jewish people do. Jewish people have also always been instructed on how to live in the “diaspora”, but all that upward mobility in society, which led to the integration of Jewish people into the majority society, was accompanied by their need to assimilate. For example, the German Jews wanted to be Germans, they wanted to be part of the majority. Romani people have a different cultural stereotype rooted inside them, for them their family comes first, and the community is also an important component. That kind of “sticking together” was stronger for the Roma. Each unleashing of antisemitism in society has meant, for the Jews, that they have done their best to come into the majority society, but for Romani people that was and is much, much more difficult here. What connects Jewish people and Romani people, and what has always connected them, is that they are destined to live on the outskirts of society, and each time society ends up in a crisis, those two groups have come under fire. I am saying this today, absolutely as loudly as I can – the Roma have always been and still are under much more intensive fire here than the Jews are.

Q: You mentioned that the Roma are still wearing that imaginary Jewish star – what does that mean?

A: The Jewish star I mean is a symbol of exclusion for me – “Hey, look, a Jew!” If a symbol of exclusion becomes part of the legislation of a state, as happened during National Socialism, then that means the state authority has been sanctified with the power to get a hold of a person who is thus stigmatized and labeled, and you can kill him, rob him, deny him work, lock him up, shove him behind barbed wire … Romani people here are stigmatized like that even today, after 30 years of democracy. They are not equal fellow citizens here! My friend, the artist Ruda Dzurko, who is no longer among us, painted a triptych called “Nazism, Communism, and This Democracy”. What he was saying was that even if the regime changes, unfortunately the destiny of the Roma doesn’t change that much.

Q: For the existence of a healthy society, according to you, what is necessary is dialogue among different people. However, today the problem is people do not listen to each other – do they lack empathy? How can society be educated to have solidarity with itself, compassion for others?

A: We don’t live in tribes anymore here. That is because people live much more in cities, in industrialized territories, and that means many of the natural communication channels have been disrupted. If you’re asking how people learn solidarity, how to communicate, how to speak with each other … that begins in the family. If our family fails, then we can be certain that we will fail our entire lives. The fact is that life in our “bubbles”, as we are calling it today, may sound like a bit of a cliché, but people have already accustomed themselves to it and it seems normal to them to just encounter those with whom they are on the same wavelength. I personally don’t like this all that much, because on the one hand, life is much more varied than it seems when we stay inside these bubbles, and on the other hand, we will never learn to see the world as others see it if we remain in our bubbles, which means we will not learn how to live together, either. We have never lived in as much peace and democracy as we are right now, 30 years after the revolution. We are wallowing a bit in our own comfort. Some people have to experience poverty and see others suffer to feel the need to give a helping hand to them. However, one does not learn either solidarity, or dialogue, or empathy, from all these books and all this media. I know several people for whom all it took was to spend 14 days at the Moria refugee camp and they came home absolutely changed, with a completely different perspective on migrants and difference. Some people may be incorrigible, but that’s a different discussion.

Q: In your view, should there be limits on freedom of speech, or can the democratic competition of opinions cope with openly racist attitudes like those represented by the election campaign slogans about “extermination” in Most?

A: Those limits are already defined. If you infringe upon the freedom or the life of another, then you’re out, according to the rules of the game. It’s even anchored in Czech legislation that professing the offensive ideologies of Communist and Nazi propaganda is illegal – but despite that, we still have a Communist Party here. To infringe upon somebody’s freedom and rights is a crime, but despite that, when some of us filed a crime report about those election billboards in the Ústecký Region, nothing came of it. After six months, we got a notice from the court that it was not found to rise to the level of a felony. We did report it, though. In other words, the existing limits are unfortunately being violated. Today my friend Andrej Bán called me, he is the co-founder of the organization “Forgotten Slovakia” (Zabudnuté Slovensko). He travels all over the country holding discussions with Nazis, leading what they call “dialogues in the field”, which is an important thing. He called me, absolutely aghast, because they published something on Facebook, and during 24 hours there were 100 comments responding to it, 95 of which were absolutely aggressive and distasteful. I said to him “Andrej, for God’s sake, that’s been my life for the last 30 years! Look, I banned comments on my blog, but if I write ‘Good morning’ to somebody online, the response is antisemitic, repulsive comments.” He asked me if I read those comments, and I told him that I actually read about 40 % of them. It may be horrible, and it hurts, but I want to know where I’m living. I want to know whether, if I walk along the square here, 30 % of the people who pass me by might hit me or want to lynch me once the right conditions arrive for them to do so. It’s a good thing to know – one must be alert, cautious, one has to fight, one has to defend oneself, and one has to have one’s own opinion. How else will you discover what evil is if you never come into contact with it? Basically, we would not know what good is if there were no evil. The line of demarcation is clear. Where there is the threat of violence, where one’s life is at risk, there is no need to hesitate, not even for five minutes. You know, it’s one thing if somebody calls you a “stinking kike”, but it’s something else altogether if they refuse to hire you because of your origin and you don’t have the means to support your family and you have to go live in the destitute conditions of a ghetto. Romani people are experiencing the fact that if one has the surname Demeter, or Horvátová, like you, then they won’t even call him for an interview. Or it happens that somebody with the surname Gál shows up, and they see he’s black, and suddenly they don’t have an open position anymore. That makes me terrible angry.

Q: Have you found an answer for why we are not succeeding in eradicating antigypsyism?

A: No, and you’ll never find one, it’s the same as if you were to ask me why antisemitism exists. It just exists, during the course of history, and it’s a part of our lives, just like evil. We must live with it and be prepared to live with it. It will always be here. I cannot imagine a world where evil and differences among people are eradicated. I can’t. However, now that I’m talking about this, once I was with Polansky in a Jewish religious community, and he was talking about his investigation with Romani people into the Holocaust of the Roma, and a little Romani girl joined the discussion, she was very nice, and she said: “Tell us, Mr Polansky, what’s it like with Gypsies and anti-Romani racism in America?” He looked at her and said “most people in America look Hispanic”.

Q: Generally, any society defends itself against taking responsibility for its failures – do you believe society is afraid of all the possible claims minorities might make? I’m referring to the sterilizations, segregation in the schools, racist demonstrations, etc.

A: The National Socialists came up with this – if somebody is, according to their ideology, inferior and a so-called second-class person, then that person has to be a slave, or he can be displaced, or annihilated, and that is a component of that ideology, in short, such people are meant to be erased from the map of humanity. The fact that this was also done during communism, and that it was done more or less secretly, and against the will of those people, is something horrifying, because the Communists, after all, came to power with slogans and ideas that were a bit different from that. When I first found out about the forced sterilizations, a chill went down my spine.

Q: When did you basically begin taking an interest in the subject of the sterilization of Romani women? How did you manage to get them to open up to you and speak about what happened to them?

A: Romani people open up just like I open up to a person whom I trust, and for them to trust somebody, they can’t perceive that they’re speaking with an attorney, a doctor, a teacher, or a white, yellow or black person … They have to perceive him as a buddy, a partner. For you to be perceived like that is not a matter of just spending a week with them with a camera or a Dictaphone. I grew up in a neighborhood in Bratislava that used to be a Jewish and Romani ghetto, so from my early childhood I went to preschool with Roma, Jews and Germans. For me it was something absolutely natural. The king of our entire quarter was Kajto, a Romani boy who was intellectually extraordinary and who was a recognized authority on the entire region. If Kajto said something, it had to be true, we took it under consideration. My communication with Romani people is absolutely different than other people’s because of this, even 50 years later it’s absolutely natural. I remember that once I was walking with my brother down the street after the November 1989 events, and we met Kajto, and he told us that for the gadje [non-Roma], “solving” the Romani “problem” means annihilating them. I have never forgotten what he told me that day.

Q: What do you make of the fact that Romani women have not yet been compensated [for being sterilized without their informed consent] despite the fact that the Fišer Government expressed regret?

A: I remember Markus Pape and Čeněk Růžička coming to me, and hiring a lawyer to put together the documents, and the Committee for the Redress of the Roma Holocaust was created. I remember Markus and all those around him who had to literally track people down and tell them how to apply for that [Holocaust] compensation. It was a complex procedure, in its way. What became apparent was that the Jewish community was better organized and had more people who could cope with communicating in many different languages while negotiating with the authorities abroad.

Q: Any societal changes always impact minorities harshly. Was that the case of the Roma in the 1990s?

A: I remember big [Romani] families who moved immediately after November 1989 to Holland, Britain, Germany, and applied themselves there. I know this very well because many of them were my good friends. The radical change consisted in the fact that those barriers fell away and facilitated their attempting to live elsewhere. The first experience was that their children were able to study there. Many of those who left found non-traditional employment outside the Romani community. Those are the positive changes. Those who remained here had to face the same problems as the rest of the population. The problem of unemployment, for us, was an absolutely new phenomenon. The dissemination of drugs and of organized crime was another new problem that nobody had anticipated. Naturally, the weaker people were afflicted by all of that more intensively and confronted with it far more than anybody else. For example, the Romani people in the settlements in Slovakia, or here in the Czech Republic in the ghettos, were among the first to be affected by unemployment, drugs and crime.

Q: You are working, among other things, as a sociologist, you have long taken an interest in Romani people and Romani subject matter. If you were to look back on these 30 years after the Velvet Revolution, how, from your perspective, are Romani people faring today?

A: Currently I’m visiting schools and debating with students born after November 1989 who don’t have any idea what it is not to be free, they don’t know what it is when you can’t cross the border of the country where you live. For me, it’s amazing to see what they are like, how people today are living and thinking. Nevertheless, the stories of their parents and grandparents are also inside those people. They still carry inside them what happened to their forebears during the war. Just as, inside me, there is the stigma of Jewishness, in them there is the stigma of their parents and grandparents – the Romani stigma, the stigma of people who are not free. In their own way, our children also carry with them the problems, woes and stigmas of their loved ones. The consequences of this are different right now, much softer, that’s all.

Q: Today the Romani people, unlike during the 1990s, are not making it into high-level politics. The concept of a Romani political party has failed.

A: Coincidentally, I have just published a piece in Slovakia where I wrote that the last really civic candidate list in free elections there was that of the Public against Violence in the year 1990. Our candidate list had candidates who were Romani, Hungarian, environmental activists, even reform communists from the Regeneration Club, and we did not at all differentiate among them on the basis of ethnicity, religion and such, everybody was just on the candidate list together – but that was the last time that happened there. They were also in Government, in the Parliament, both the Czech and the Slovak ones. Today in Slovakia there are four Hungarian political parties, which makes my hair stand on end in horror, because the more we differentiate among each other on the basis of ethnicity or religion, the worse it will be.

Q: You co-founded TV Nova at the beginning of the 1990s – what is your perception of how its viewers today are informed about Romani people?

A: Private media are dependent on advertising revenue, and that is dependent on ratings, and those are dependent on the tastes of the majority. That is why most commercial media pander to the majority taste. Today most people have no idea what they want, they are just suspended in this infinite confusion of information.

Q: Why aren’t there more Romani moderators in the media? Why is so little room given to Romani people and minorities generally?

A: We complained back when Ivo Mathé was the director of [public broadcaster] Czech Television that Romani people were not appearing on our screens as journalists and moderators. It didn’t yield a very big result. I would like to see a Romani anchor during the regular newscast. The media should have a civic character. I shouldn’t have to go to Romea.cz if I want to discover what’s new in the Romani community, it should be enough to open up any news website, to turn on the radio without having to wait for the Romani broadcast to come on. This type of ethnic and religious selection really angers me, because it is creating exclusivity here.

Q: What is your view of the media situation today, when the big media outlets, now including Nova, are owned by Petr Kellner and his PPF Group – are the oligarchs dominating the connection to political life?

A: Corruption has been a problem since time immemorial. It’s just like the “truth and love” issue. There is no need to stop playing the game, though, even if the solution is nowhere in sight.

Q: The racist murders of the 1990s [in Czechoslovakia] are almost forgotten today. Is that the reason you decided to document [2009 Romani arson victim] Natálka’s story?

A: I can exactly remember Markus Pape calling me that morning and describing to me what had happened. I looked online and immediately called my friend, the cameraman Martin Hanzlíček, we got in the car, and on the way there we contacted another friend, the child psychiatrist Petr Pöthe. Then Milena Tučná called and got in her car with donations and we drove to see the family of Natálka, the burn victim. Petr Pöthe soon discovered that we were too weak of a team, because the family needed permanent therapy and it takes four hours to travel between Budišov and Prague by car, so Pöthe chose Přemysl Mikoláš, a therapist from Havířov, and called him and said “Přemysl, help us, it’s impossible for us to commute there every week.” It wasn’t any institutions, it wasn’t the state, these were human beings who didn’t have to be convinced, who immediately got involved. Petr Pöthe, who is an experienced psychotherapist, said: “We are not allowed to create a situation in which this family becomes dependent on us. Our mission is aid them to live again, to get them back on their feet.”

Q: Are you still in contact with the family?

A: If I want to know today how the family of Natálka is doing, I call Kumar Vishwanathan. Last time he told me that if God wills it, their oldest daughter, Kristýnka, will pass her high school exit examination, and that is no small thing, because suddenly the weight of the entire family will be on her shoulders. The younger daughter, Kornelka, has a child of her own and a partner, and Natálka has another series of operations ahead of her, because her artificial skin is not growing. Natálka is already a big girl, but she will bear the burden of what happened for the rest of her life, she has been marked by it forever. What is amazing is that her parents are still married. A gadje [non-Roma] family would have divorced fifty times by now if they had to confront problems that are so burdensome. I remember how Kristýnka was invited by then-Prime Minister Fišer to London, she stayed there for about a week, we accompanied her to the airport. When, one week later, we were waiting for her there again and we brought her home from the airport, we asked her what she was looking forward to the most, and with tears in her eyes she said “Our family”. In my opinion, you wouldn’t find that among the gadje [non-Roma] so easily. After a traumatizing experience at home she was returning from London, where she had anything she could want, and the only thing she was thinking about was to be with her family again. That is the inspiring, strong affiliation, belonging, and mutual care that members of Romani families are able to give each other.