Czech TV series paints northern town as a ghetto - just like local politicians do

The second season of the “Rapl” television series, judging by the feedback on social media, is not exactly firing people’s imaginations. Naturally, that’s not important – public broadcaster Czech Television and others have already produced enough detective series featuring Detective Martin Tomsa and based on his hopefully-developing stories.

What is interesting to us here is why the producers’ gamble on Ústí nad Labem as an attractive film location hasn’t paid off. “The Ústecký Region is one of contrasts and diversity where filmmakers find unique landscapes for any story,” reads the website of the Film Office of the Ústecký Region, which brought the filmmakers to Ústí nad Labem.

The Film Office wants the filmmakers to return – and not just them: “This will yield returns for our region, both as an economic effect and in the opportunity, through films and television programs, to support the promotion of our region as an attractive tourist destination. We see the positive benefits of audiovisual productions for this region and we want to actively take advantage of them!”

The positive benefit of this new season of “Rapl” consists roughly of the message that any civilized person would avoid this town on the Elbe River if it were at all possible. If you have no choice but to go there, you should keep your wits about you.

The series shows not just people’s wallets at risk, but their very lives. This heavily-tested region couldn’t have asked for “better” promotion.

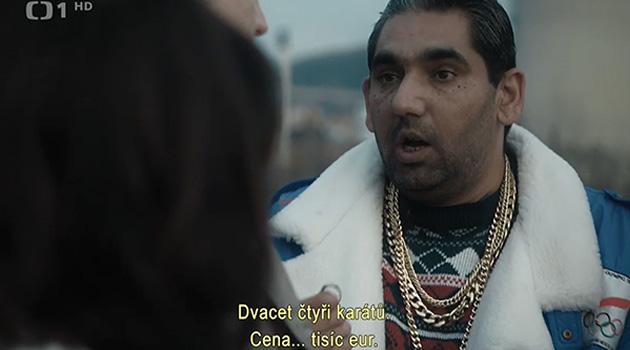

Echt gold. 24 carats

Betting on an attractive film location in association with the character of Major Kuneš has already paid off twice. The “Cirkus Bukowsky” series performed a detective story in attractive localities of the Děčín industrial area – for example, in the dockyards at Křešice or the harbor at Loubí.

Responses to the production were enthusiastic, both from local patriots and from the public unfamiliar with the beauty of that inshore town. The spin-off of that series, in which the producers created “Rapl” around the solo adventures of Major Kuneš, enjoyed an initial success.

The town of Jáchymov and the plains around the Ore Mountains (Krušné hory) played well as settings, and for those who were unfamiliar with them, the producers discovered the darkly magical grounds of the former Sauersack tin mine near Přebuz. The murky stories of Nestor Bukowsky and Major Kuneš took place in both the Děčín and the Ore Mountain locations against backdrops that were not at all disruptive.

Those episodes worked as stand-alone pieces. In short, the viewer would have been interested in them even if Detective Martin Tomsa had come wandering back into the script.

Why has this not succeeded with Ústí as the setting? Or better said, why hasn’t it succeeded so that audiences say to themselves: “That’s gorgeous, I want to see that!”?

The answer to that is easy: The city is being depicted as an excluded locality. Some aspects are being greatly exaggerated, compared to reality, or taken absolutely out of context.

In the third episode of “Rapl”, a Romani family tempts court pathologist Knecht by telling him “Das ist echt gold. 24 carats” as they attempt to defraud him. The pathologist, naturally, falls for their scam.

The situation is based in real events and is as much a part of Ústí as it probably is of Teplice, or of Kralupy nad Vltavou, or of any town located near the highway in the Czech Republic where, roughly since 2011, gangs of Romanian Roma in Mercedes (also for sale) have been operating. The gang members pretend to be in desperate straits and rip off willing passers-by with the aid of invented stories in which fake gold plays the main role.

Later in the episode, Kuneš sets out to investigate the Romani family by visiting their winter camping ground out somewhere in a field, a genuine slum with caravans and tents. Honestly, Ústí nad Labem does have many problems, and most of them are somehow associated with excluded localities, but still, here in the Czech Republic people do live in a bit more civilized fashion than is being depicted by the series.

Who wants to see the ghetto?

Certainly such an example is one of fictional, filmic license. It just happens to directly contradict what the local politicians and the film agency they are managing intended.

The filming of “Rapl” was a hit in terms of self-presentation all last year for those who apparently deserve the credit for bringing the filmmakers to town. As such, the production also played a certain role in last year’s election campaigns.

On the town hall’s website we can see an article of such praise, for example, on 24 September. The filmmakers are said to like how the town representatives met them halfway, and the town promises people will see beautiful locations in the series.

“The film was shot in many important locations such as Chateau Větruše, the Marián Bridge, Střekov Castle, the hospital, Tovární Street, the mall, on the streets of the town and at Milada Lake. Non-traditional locations were also used such as the cable railway and the trolley buses,” the article reads.

One might believe from this that the second season of Rapl would be full of product placements in which the town beneath Střekov Castle would be the main attraction. That would be a mistake.

The main character in the series is the ghetto itself – drugs, Nazis, and a mafia associated with politics. It is exactly the image of North Bohemia that the people in the local film office probably did not have in mind.

It is certainly ironic that the very same leadership has now decided, according to that same stereotype, that the town must officially be designated one big ghetto. They have done so by declaring its entire territory, not just its problematic localities, a “housing benefit-free zone”.

Their justification is based on a very suspect assessment by the local social welfare department, which alleges that the danger posed by alcohol and drug use, by children’s truancy, and by the habit of not working – which is, moreover, allegedly passed on to children by their parents – as well as various other sociopathologies have spilled out of the excluded localities into the town as a whole. Just as viewers who know the town are amazed by the version depicted in “Rapl”, other people who live ordinary lives in Ústí nad Labem are amazed that the town has described itself this way.

Property owners who believe the local regulation is bringing down the value of their apartments and houses are even more embittered by the decision. They are placing their hopes in the Constitutional Court, which should soon decide the issue of these zones.

Ústí nad Labem wanted to be seen as an unjustly forgotten jewel. That did not succeed – this has been a wasted opportunity.

The worse things are, the worse they get. That applies in the real world, not just to the visions of politicians who continue to destroy this town with their populist, short-term ideas.

First written for the Institute of Independent Journalism, an independent nonprofit organization and registered institute involved in providing information, news reporting an journalism. The Institute’s analyses, articles and data output are available to all for use under prearranged conditions.