Czech teacher told "special school" pupil she'd never finish 10th grade, but today she's at university

"It doesn't matter where you apply, they'll expel you during the first year," a teacher told Vanesa at the end of her final year of primary school (9th grade); her guidance counselor wasn't so abrupt, but she did recommend Vanesa apply to apprentice as a florist. "It wasn't because I have some special relationship with flowers, but because they say it's one of the easiest programs," Vanesa Harvanová (19) recalls.

Today she is studying in her freshman year of Social Work and Social Policy at Jan Evangelista Purkyně University in Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic. The road to studying at university was not easy for her from the very beginning.

Harvanová grappled with a speech defect in childhood and visited a speech therapist while still in nursery school. She attended grades 1-9 at schools specializing in children with speech defects.

The special instruction aided her with overcoming her difficulties. When it came time to decide where she should attend high school, though, she was a “clear case” for most educators and her guidance counselor – with her diagnosed dysgraphia, dyslexia and dysorthographia, they didn’t believe she had good chances of being accepted.

“Almost nobody at school said to me back then: ‘Chose something you might enjoy and try it.’ One teacher told me straight out that it didn’t matter where I applied because they’d expel me in my first year,” she says.

Harvanová was startled when her guidance counselor recommended she choose a specialized training school instead of a high school – she didn’t want to become a florist, she had no relationship to the field. “I was in a terrible jam,” she says.

“I had my own ideas, but suddenly they began persuading I should head in a completely different direction,” Harvanová recalls. Ultimately she was not deterred and she applied to two schools she chose on her own, a high school with a focus on pedagogy and a high school with a focus on the travel industry.

Harvanová was accepted to both. She chose the high school with a focus on the travel industry.

“Ever since I was little, my parents had encouraged me to study. They’d have supported me even if I’d chosen to become a florist, as long as it was something I enjoyed and wanted to do,” she describes her parents’ attitude.

What attracted her to the travel industry was the focus on geography, history, and working with people – she wanted to expand her horizons. The change to working in classrooms of 30 students, compared to her primary school where there had been 10 children in the classroom at the most, was demanding at first, but she enjoyed her studies, graduated, and was accepted to university.

I ignore all the allusions to my ethnicity now

Harvanová was one of many Romani classmates at her first primary school specializing in pupils with speech defects in the Čimice neighborhood of Prague, but when she transferred in the fourth grade to the Don Bosco Church Speech Therapy Primary School in the Bohnice neighborhood, there were far fewer Romani pupils; at high school she studied with just three other Romani girls, and at her university she has encountered just two other Romani students so far. When she first attended a meeting three years ago of the Baruvas (We Are Growing) program held by ROMEA as part of its Romani Scholarship Program, it was a strong experience for her.

“Up until then I’d known about another 15 or so Romani people from my neighborhood who were attending a secondary vocational school or a high school, but to suddenly encounter so many Romani students from high schools and universities, in so many different fields, was literally a shock. Naturally it’s a positive one,” she says.

In addition to making friends with her fellow Romani students from all over the country, the opportunity for them to share their experiences with each other is important to her. “It’s quite inspiring to see how people progress, whether at school or at work, everyone has goals they are pursuing,” she says.

These students still encounter distrust from non-Romani people, who make allusions to their Romani origins. “Over time I’ve gotten accustomed to that, I don’t take it seriously anymore although I’ve encountered it quite frequently my entire life,” she says.

Her most recent experience is from her first semester at university – an older student with whom she attends different subjects has repeatedly raised her hand in class to make remarks about how Romani people allegedly “abuse welfare”. “Once, for example, she alleged that social benefits aren’t really welfare, but basically ‘extortion’ so the Roma will leave the majority society alone,” Harvanová says.

“I quite appreciated the approach of one professor who analyzed the welfare system for my classmate in detail and made it clear that what she was saying was utter nonsense,” she relates. Soon she will be concentrating mainly on her studies and exams.

She is making plans for the future, though. One area that interests her and that she would like to learn about is diplomacy.

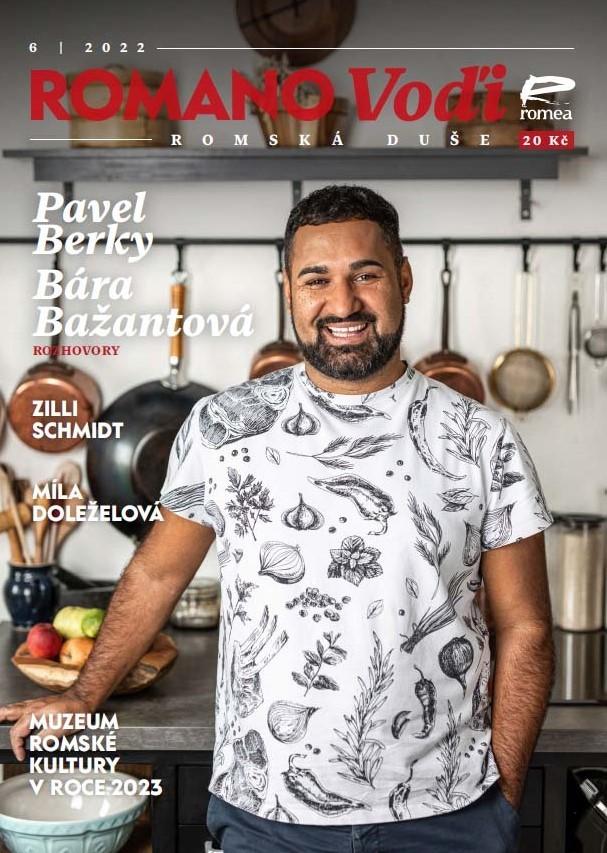

First published in Czech in Romano voďi magazine 6/2022 – www.romanovodi.cz