Czech project presents the stories of those whose family histories reflect dramatic historical events of the 20th century, Roma and Sinti included

On Monday, 11 November at Cafe Therapy in Prague, a discussion was held as part of a series organized by the Schola Fidentiae organization's project called "Shared Experience: How can the memory of the 20th century as 'the century of wars' aid the 21st century?" The discussion, moderated by historian Michal Schuster, was called "Shared Experience: Roma and Sinti Memory of the 20th Century - Living, Discovered and Overlooked" and featured three Romani guests: Renata Berkyová, a Romani Studies scholar working at the Institute of Contemporary History of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic; Růžena Ďorďová, who is an activist and field social worker with the Salvation Army; and Yveta Kenety, Assistant Director for Student Life at New York University in Prague.

Shared Experience

Schola Fidentiae was established in 2020 with the goal of working on education about various subjects related to the dramatic events of the 20th century – the Second World War, the Holocaust, and other events which were fundamentally groundbreaking, the repercussions of which persist to this day. “Connecting the past to the present is one of our interests and tasks we are involved with, whether through educational seminars and workshops for teachers and pupils or discussion programs for the public,” said Schuster.

The “Shared Experience” project focuses on finding the barriers to and opportunities for a common sharing of the experiences of the traumatic events of the 20th century and coming to terms with them, both in the memory held by families and that of the general public. “We are trying to present the stories of people whose family histories were fundamentally impacted by these events in particular. During the previous six discussions we focused on the subject of how the memory of the Holocaust of the Jewish people and the Romani people can be passed on to future generations. We discussed the role of what’s called the second or even third generation, i.e., the descendants of the survivors – how these events have or have not been spoken of in families, how they share these experiences and family memory with their children and grandchildren,” described Schuster.

The subject of the November discussion was 20th-century events linked to the persecution and genocide of the Roma and Sinti in particular. “However, this also includes other historical traumas such as, for example, the forced sterilization of Romani women and many others. These traumas are inseparable, living parts of the family memory and collective memory of Roma and Sinti. Be that as it may, we know that in many families such memories were suppressed or displaced for different reasons, so the new generation often has had to rediscover them,” Schuster said, adding that the majority society is also rediscovering and should be rediscovering them because they have been absolutely ignored on various levels, marginalized, or suppressed for decades, including in the areas of education, public remembrance, and research.

A story that was forgotten – until it was rediscovered

“It was an old cupboard and it occurred to Mama to raise up the bottom of it. There was a box down there that she put in her purse and didn’t open until she got home. There were military medals in it,” Ďorďová told the story of how her mother discovered the first proof of her brother’s wartime heroism, Ďorďová’s uncle, Imrich Horváth.

Ďorďová met her uncle when she was 10 years old; he died later that year. “We discussed the subject of the war a great deal in our family, we passed on the stories he had confided in my mother. Now it’s my turn to pass on his experiences,” Ďorďová said.

Horváth’s story would have remained totally forgotten if Ďorďová hadn’t spoken of him during a panel discussion marking Roma Holocaust Remembrance Day in the summer of 2016. Czech Radio reporter Iveta Demeterová and journalist Markus Pape then researched his life, which yielded an unusual story: Imrich Horváth was from the small Slovak village of Seňa in the Košice area and made a living as a blacksmith, among other jobs.

When the village was annexed to Hungary during the Second World War, Horváth had to enlist with the Army of Hungary and fought on the eastern front. He switched over to the Red Army there and in 1943 joined the foreign units fighting for the Army of Czechoslovakia.

Horváth fought in the Carpatho-Dukla operation and in the Slovak National Uprising, where he was injured, captured, and deported by the Nazis to a prisoner of war camp in Germany. After the Americans liberated that camp, he offered to fight for them.

“We don’t exactly know where he was deployed, but he probably joined the guard units which were supposed to protect the American Army on Czechoslovak territory. That was the case of most of the Czechoslovaks who fought together with the Americans,” Pape told news server iDNES.cz previously.

Horváth made it to Plzeň with the American Army and remained there after the war. Ďorďová said her family’s experience with these wartime events impacted her whole life – she actively joined the fight for the rights of Romani people, the fight to remove the industrial pig farm from the concentration camp site in Lety u Písku, and the fight for more widespread awareness of the Holocaust of the Roma.

“Today there is already a beautiful memorial in Lety. However, I’m still going – now I’m aiding homeless people who urgently need assistance. I will never stop fighting,” Ďorďová said.

History, the present, identity

Yveta Kenety has an experience of how such fundamental events were not discussed for a long time in her own family. Her father was born just before the Second World War began and both his parents died during the conflict.

“They weren’t Holocaust victims, but it may have been connected with the war somehow because they probably died of typhus. My Dad, as their youngest child, was sent to a foster family, did his military service at the age of 18 in Moravia, and totally lost contact with his family. He joined the non-Romani community and basically denied his Romani identity for the rest of his life,” Kenety said.

Kenety said her father did not want her to find out that he was Romani because he believed it was a burden he did not want to pass on to her – what’s more, when he married he took his wife’s surname. When she was 25, Kenety learned of his origins purely by accident.

Her father’s lifelong rejection of his Romani identity inspired Kenety to get involved with Romani-related subjects. She started meeting other young Roma, worked as director of the Athinganoi organization and the Romani Student Information Center, then as the national facilitator for the World Bank initiative called the Decade of Roma Inclusion, and then coordinated the scholarship program for Romani students for the Roma Education Fund and the ROMEA organization.

Renata Berkyová comes from a Romani and Sinti community in Slovakia and is also discovering her family’s history thanks to her own academic research and study of history. Her family has many memories of the communist era, but in the 1990s, when she started taking an interest in her family history, nobody was still alive who could recall the Second World War.

Berkyová’s great-grandfather fought in the Slovak National Uprising. She plans to focus on thoroughly researching her family history even after completing the dissertation she is writing as a doctoral candidate in social history at Charles University’s Faculty of Arts.

She described the crucial moment that brought her to the study of history as being her involvement in a media project of the ROMEA organization during which she worked on a short documentary film called “Stíny romského holocaustu” (“Roma in the Shadow”). “The subject of that struggle to officially remove the industrial pig farm from the site of the former concentration camp in Lety u Písku very much affected me and I decided to dedicate myself further to the field of history, because at that time I had been more devoted to journalism. The Lety memorial was not built until this year. Although the Second World War was 80 years ago, the past we are discussing is decidedly not remote at all. It’s still a very strong, current topic. At the same time, I see my professional focus as an obligation to create better societal conditions for our children. They should know the history of the Roma is part of their own history, their own present, and their own identity,” Berkyová concluded.

“Roma and Sinti Memory of the 20th Century – Living, Discovered and Overlooked” was attended by more than 20 people who then joined the lively discussion that followed. It was held as part of the project on “Shared Experience: How can the memory of 20th century as ‘the century of wars’ aid the 21st century?” with the financial support of the Czech-German Fund for the Future.

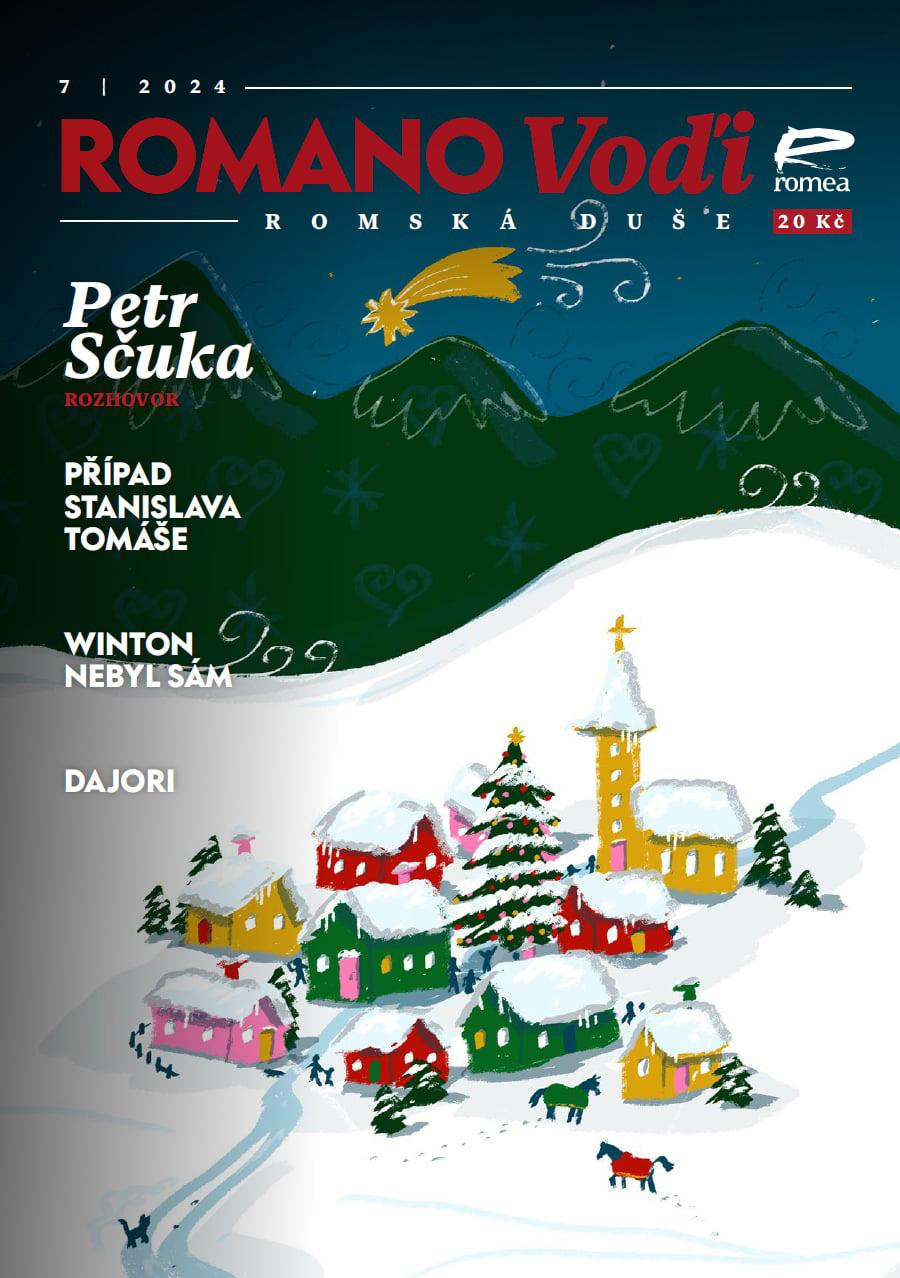

The Czech original of this article was first published in Romano voďi magazine.