Czech historian responds to tabloid disinformation about Romani Holocaust site

The “Gypsy Camp” at Lety by Písek in Bohemia was established on 2 August 1942. It was located on the site of a transit camp that had previously been a disciplinary labor camp.

Another disciplinary labor camp had also been established at Hodonín by Kunštát in Moravia by the Government of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia on 8 August 1940, the same date as the Lety disciplinary labor camp. The initial efforts to establish both disciplinary labor camps date to the time of the so-called Second Czechoslovak Republic, when Czech society, under pressure from Nazi Germany, radicalized and was inspired by the German model in the area of social policy, among other things.

The disciplinary labor camps were supposed to fulfill the purpose of correctional facilities where convicted criminals, drifters, long-term unemployed people, and other persons who were were allegedly “work-shy” (adult men only) were to be “re-educated” by performing hard physical labor. Romani people comprised just a fraction of the total number of the forced laborers in both camps during that phase.

“Gypsy Camp” begins in August 1942

In March 1942, the Protectorate Government issued an edict on “the preventive elimination of crime” (which had been in effect in Germany since 1937), and on the basis of that edict, the camps at Hodonín and Lety were transformed (with retroactive effect as of 1 January 1942) into transit camps. Through this step, these camps became part of the Nazi system, and from that moment persons labeled “asocials” were sent from them to the Auschwitz concentration camp.

The establishment of the so-called “Gypsy Camp” at Lety in August 1942 happened on the basis of a decree “on eliminating the Gypsy nuisance”, which had been in effect in the Protectorate since 10 July 1942 (and had taken effect in Germany in 1938). An inventory of “Gypsies and Gypsy half-breeds” was performed on the territory of the Protectorate, and the Czech gendarmerie, supervised by the German Criminal Police, included as many as 6 500 persons in that category.

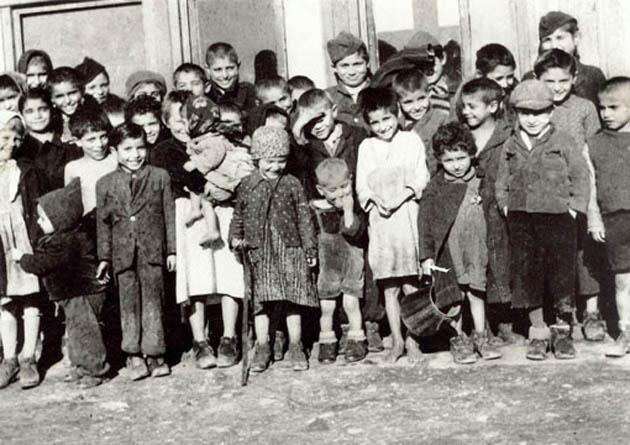

Some of these people were then interned in the newly-established “Gypsy Camps”. More than 1 300 children, men and women, most of them Romani, passed through the so-called “Gypsy Camp” at Lety from 2 August 1942 – 6 August 1943.

At least 326 of those people, 241 of them children, did not survive their internment at the Lety camp. Children, men and women at Lety died as a consequence of being given too little to eat (the Czech guards held back on food distribution and stole food from the camp supplies), of hard labor, and of catastrophic hygiene conditions, especially an acute lack of water and the fact that the accommodation capacity of the camp was enormously exceeded.

Those circumstances led to the outbreak of an epidemic of both typhoid and typhus in the winter of 1942-3, the course of which was significantly worsened by the cavalier attitude and inactivity of the camp commander, Janovský. Evidence for this is provided, among other things, by the documentation of an Extraordinary Peoples’ Court proceeding that was conducted against him after the war.

During the time that Lety had functioned as a disciplinary labor camp, forced laborers had been interned there for between three to six months, but the predominantly Romani families interned there during its “Gypsy Camp” phase were forcibly concentrated for an indeterminate length of time and were not there because of any criminal misconduct of which a court had convicted them. They were interned at Lety because they had been labeled “Gypsy and Gypsy half-breed” families and were meant to remain there until the Nazis decided their fates.

The memories of the eyewitnesses to these events have been systematically recorded by staffers of the Musuem of Romani Culture ever since that institution was created. Many of the oral histories of Romani people who survived the Nazi genocide have been published by the Museum in book form (e.g., Ma bisteren, 1997) or in audiovisual form (…to jsou těžké vzpomínky, 2002 and Odtud nemáte žádnej návrat…, 2015).

The fate of Romani people during the Second World War is also the topic of one of the halls of the permanent exhibition of the Museum of Romani Culture. The Romani children, men and women interned at Lety were forced to work in a stone quarry and on the construction of roads, and their labor was exploited in agriculture and forestry – but the purpose of the camp was not “re-education through labor”.

Those imprisoned at Lety were meant to await the “Final Solution to the Gypsy Question” there. That arrived in December of 1942 with the so-called Auschwitz Decree of Heinrich Himmler.

According to that document, Romani people from Central and Western Europe were to be transported to the so-called “Gypsy Camp” in Section B II e of the Auschwitz II-Birkenau concentration camp. More than 500 Romani people from Lety were also included in those deportations, 420 of whom were sent to Auschwitz by the transport of 7 May 1943.

Most persons so deported did not live to see the war end. As of March 1943, Romani people who had not been interned in the so-called “Gypsy Camps” of Hodonín and Lety, and who had remained at liberty up until that time, were also rounded up and sent to the “Gypsy Camp” at Auschwitz.

After the war, just 583 Romani people returned to the Czech lands (Bohemia and Moravia) from concentration camps elsewhere. Today in the Czech Republic, the opinion is frequently expressed that the “Gypsy Camps” of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia – Hodonín and Lety – were not “concentration camps”.

The most recent person to express that opinion is a history professor, PhDr. Jan Rataj, CSc. He did so in an interview given to ParlamentníListy.cz (9 September 2016).

Professor Rataj is quoted there as saying the following: “From a technical perspective, the camp at Lety was not a concentration camp, but a prison labor camp, and later it was specifically a collection camp.” He also states that: “There was not a single concentration extermination camp… on the territory of the Protectorate.”

Both of these claims are presented within a single paragraph, and Professor Rataj very quickly moves from the term “concentration camp” to the term “concentration extermination camp”. Later on in the text of the interview he mentions the concentration camps at Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Dachau, Mauthausen, Ravensbrück, Sachsenhausen, and others.

When assessing whether, in certain concrete cases, what we are discussing is a “concentration camp” or not, if we use the definition of a “concentration extermination camp” – as the professor has in the case of the Lety camp – then we would come to the conclusion that not all of the camps the professor named in this interview were “concentration extermination camps” either. The camps most frequently discussed as extermination camps are the concentration camps of Auschwitz-Birkenau, Bełżec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Sobibor and Treblinka.

The Nazi camp system included thousands of camps with various designations, epithets, and titles. Professor Rataj, when considering the appropriateness of the term “concentration camp” in connection with the so-called “Gypsy Camp” at Lety, is apparently using stricter criteria than those he uses when he calls other camps “concentration camps”.

The question posed to him by the ParlamentníListy.cz reporter was already phrased in a thoroughly leading, suggestive way, asking whether it is possible, when discussing the Lety camp, “to say on the basis of historical facts that it was a concentration camp in the sense of the meaning we all connect with that term.” This apparently vague formulation actually has a meaning that is comparatively easy to discern.

In the instruction of history in the Czech schools, and in general historical awareness here, the image continues to persist of concentration camps as places where the heroes of the Czech Resistance and the Jewish victims of Nazi racial persecution suffered. The Holocaust of the Czech and Moravian Roma, to a significant degree, remains a so-called “unknown” Holocaust here – even though today this is rather due to society’s lack of interest than to a lack of accessible information sources.

From this perspective, therefore, it seems that Lety could not have been a “concentration camp” – and what’s more, according to Professor Rataj, it is not possible to compare the suffering of the Roma interned at Lety with the suffering of the Czech Resistance fighters in the Nazi concentration camps. Here it is interesting to note that the term “concentration camp” is also commonly used in the Czech Republic, for example, to refer to Terezín.

According to the strict criteria used by Professor Rataj in this interview, however, even Terezín should not be referred to as a “concentration camp”. Be that as it may, it is important to realize that it is possible to use the term “concentration camp” beyond the context of the extermination camps of the Nazi Third Rech.

It is a comparatively well-known fact that one of the oldest usages of this term is connected with the camps built by the British to imprison Dutch women settlers in southern Africa (called the Boers) and their children [Translator’s Note: during the Second Boer War (1899-1902)]. We hope that Professor Rataj does not want to relativize the suffering of the Boer women who were forcibly moved from their burned-down farms into tent camps where their children died by the hundreds in shocking hygienic conditions.

We also hope Professor Rataj does not intend to relativize the suffering of the Romani people who were interned in the overcrowded camp at Lety and died there as a consequence of infectious diseases and undignified living conditions. Similarly, we hope that nobody else wants to relativize the suffering of the heroes of the Czech Resistance who died in the concentration camps.

In his statements in this interview, Professor Rataj also says people of “ethnically non-Gypsy origin” were released from the Lety camp. If he means the roughly 150 persons released at the end of May 1943, it is certainly much more precise to state that these were persons who were declared “non-Gypsies” on the basis of anthropological, physical criteria.

Many of those released from Lety whose testimonies were then recorded declared themselves to be Romani. A “non-Gypsy” ethnicity was ascribed to them on the basis of the racial criteria of the day.

In his answers to these questions, however, Professor Rataj does not take into consideration the difference between the racial definition of “Gypsies” at the time and the contemporary concept (and self-definition) of Romani people – without any reflection, he uses the expression “Gypsies” (but without scare quotes) to describe both those targeted by Nazi persecution and the members of the Romani community today when expressing his views of the contemporary situation. This fact appears to be symptomatic of his perspective on the Romani minority, past and present.

His uncomplimentary attitude toward the Romani minority and his belittling of the suffering of Romani people is also reflected in his allegation that the guards at Lety could not have been at all strict (and that Lety, therefore, does not fulfill one of the typical aspects of a concentration camp) because allegedly one-quarter of the forced laborers managed to flee. This assertion, of course, is not based on facts, and was probably arrived at by comparing the number of persons who fled with the number who were released.

It is an indisputable fact that the internment of Romani people in the so-called “Gypsy Camp” at Lety was in preparation for the “Final Solution to the Gypsy Question”that had been prepared for many years by the Nazi high command and by pseudo-scientists “researching race”. The Lety “Gypsy Camp” fulfilled the function of concentrating the Romani people of Bohemia, who were then sent from there to the extermination camp of Auschwitz II-Birkenau.

At Lety the Romani prisoners were supervised by Protectorate security forces whose members frequently abused and beat them. As a consequence of substandard diet and hygiene conditions, a significant death rate happened there that exceeded, for example, the death rate of the concentration camp at Dachau percentage-wise.

According to Professor Rataj’s narrow definition, Lety allegedly was not a concentration camp. According to the facts presented above, however, it is possible to call the so-called “Gypsy Camp” at Lety by Písek a concentration camp, without exaggeration.

Mgr. Dušan Slačka is an historian working for the Museum of Romani Culture.