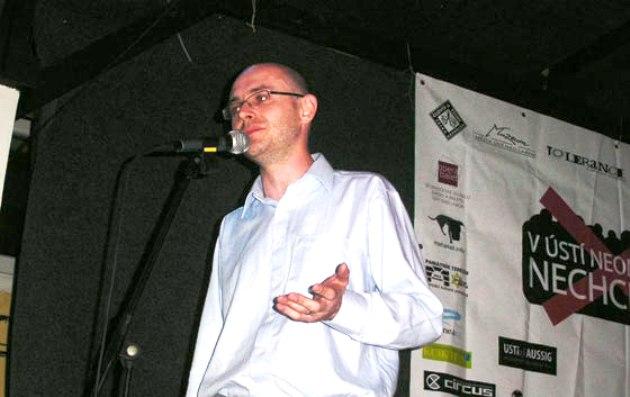

Czech anti-racist activist Míra Brož: Pogroms with Romani deaths, or a Romani Malcolm X, may be the future

In this interview with the pro-Romani activist Míra Brož of the Konexe civic association, we discuss the current situation among activists, the state of civil society, the role of nonprofit organizations, and the dangers flowing from both right-wing extremism and radicalization inside Romani communities in the Czech Republic.

Q: The number of events with a racist subtext is rising in this country and ordinary people are participating in them side by side with right-wing extremists. How is it going with what we might call the opposition, what is the state of the anti-racist movement in the Czech Republic?

A: The greatest success has been the emergence of the Blokujeme! ("Let’s Block the Marches!") platform, which is bringing together a broad spectrum of active individuals and organizations across the country. Blokujeme! emerged during the summer, just before the anti-Roma march in Vítkov, the town where several years ago the racists almost burned a little Romani girl, Natálka, to death. That makes it the second time that this small town has sparked a wave of solidarity with Romani people. It seems that people who care about what is happening are slowly becoming active. On 24 August, when the racists held anti-Roma assemblies simultaneously in more than one town, the number of people attending events supporting the Roma community, anti-racist demonstrations, was the same as the number of those attending the racists’ events. The most recent developments include activities like the website Nicneznazor.cz, as well as coordinated postings to online social networks where discussions about racist groups are happening. People who cannot get involved directly in activities at the scene of a crisis or at the time it is unfolding now have an opportunity to do something against this racism and rising hatred from the comfort of their own homes.

Q: How did you spend this year’s "hot summer", which was completely lacking in a "cucumber season" – you personally and the Konexe association in general?

A: We are experiencing a hectic time. Previously the volunteers of Konexe worked only in northern Bohemia, but recently we have been operating all over the Czech Republic. That is the logical result of a situation in which we are addressing a key social problem, that of anti-Roma pogroms. Sometimes this just seems absurd to me, we are not set up for this and we have no resources. We have reached the limits of the opportunities available to a small, grassroots, volunteer organization with a budget of just about zero. Because of this current wave of hatred, we are not able to do anything else, we are neglecting our usual agenda. I didn’t get a vacation this year.

Q: You think it is correct to call these recent anti-Roma demonstrations "pogroms"?

A: Yes, I think that is the precise term to use. If riot police had not been at the scene, and if the mobs had actually made it to the Romani people’s homes, what do you think would have happened? These have been pogroms stopped by the police. Let’s call things by their real names. What else can we do?

Q: What does the term "grassroots organization" mean?

A: Well, "grassroots" means "from below". A grassroots nonprofit is an organization created by local, engaged members of a community who use it to help themselves and defend their community’s rights. Grassroots organizations can engender future leaders, they can bring a community together. In the Czech Republic there are not many such organizations, but we believe the situation is changing. They are sort of the antithesis to the nonprofit chains.

Q: The nonprofit "chains"? Is that a correct comparison?

A: A nonprofit chain is a big company, with its headquarters usually in Prague, that has branches all over the Czech Republic providing a standard offering of services. When a commercial chain opens a branch in a town somewhere, the effect is that smaller local retailers go out of business because they can’t compete when it comes lobbying, promotion, and the range of goods offered. The same effect happens when a small, grassroots, Romani organization is competing somewhere with a nonprofit chain against which it has no chance. The grassroots group doesn’t have financial managers who are as good, fundraisers who are as good, project managers who are as good, or relationships with local politicians. The local group will never win the competition for the money, and there is only one source of that money.

Q: Is that why the Konexe association has no money?

A: No. Unfortunately, it is even more complicated with our money and support for our projects. The situation I have described concerns many small, local Romani nonprofits that would like to hire their own social workers or run a drop-in club or a football team. They want to provide social services or recreational activities for children and youth. Konexe doesn’t want to do that. We want to do something else. The problem is that the activities we want to implement (community empowerment, community organizing, advocacy) are not included in the grants normally on offer here in the Czech Republic. Those activities are not supported, we don’t have anywhere to send our projects. Here all of the money goes to social services.

Q: You say you don’t want to do social services. Is that because you believe they don’t work? I ask because you have previously, for example, criticized the activity of People in Need (Člověk v tísni) in that respect.

A: No, I don’t see it as being so clear-cut. I know some of the field social workers from the nonprofits are idealists who are on fire, in the best sense of the word, and they do their best to help their Romani clients, they work until they drop. My own tendencies are also toward that kind of work and fervor. However, some of these people also instinctively sense that their task is similar to that of emptying the ocean with a coffee spoon. I would compare social services to ibuprofen, which relieves fever and pain for a little while, but doesn’t treat illness. Social services may relieve their "clients" of pain temporarily, but those services will not manage to change their situations. Yes, we should give ibuprofen to someone who has a fever, but at the same time we must also treat their illness. Basing a treatment program on ibuprofen alone is absurd. We are all now seeing what that leads to. In the Czech Republic it has always been believed, and many people probably still do believe, that the problem of Romani poverty will be solved by a magic cocktail, an elixir. In that cocktail we are supposed to mix together all kinds of social services – a social worker for every Romani family, a club for children and teenagers to play in a supervised environment, ancillary work for the parents, maybe some tutoring for the children – with a great deal of repression, such as supervisory services, crime prevention assistants, and CCTV systems. Abracadabra and… nothing. The cocktail doesn’t work! We are in a situation where we have an inexhaustible number of organizations providing social services to Romani people, but we have almost no organizations defending the rights of Romani people. The nonprofit chains have completely lost their watchdog role. Sometimes their role is in fact the opposite of a watchdog.

Q: Please explain this in more detail.

A: The work of a watchdog is to keep watch. When something fishy happens, the watchdog starts barking, growling, getting people’s attention, alerting everyone. In a healthy civil society, the watchdog role is one of the most important functions of a non-profit. If a wrong is done to their "clients", if their situation is critical, then the nonprofit starts barking, calling journalists, writing open letters to those responsible, pointing the finger at those who bear political responsibility, criticizing them, doing their best to create pressure to solve the problem instead of sweeping it under the carpet. This role was forgotten about by the Czech nonprofit chains long ago because they are dependent on good relations with local authorities and politicians and with their donors. The whole situation has unfortunately developed even further in the opposite direction – some organizations directly play to role of anti-watchdogs. Let me explain with the example of Ústí nad Labem. The situation in the ghetto of the Předlice quarter there is terrible, in my view it is the worst ghetto in the Czech Republic. There are buildings with no water service there, some of which are at risk of collapsing on top of their occupants at any time, there are massive piles of garbage, rats, bedbugs, cockroaches, diseases, drugs, loan-sharking – it’s just a catastrophe. This hellish situation was not created overnight, it deteriorated gradually, and it reached the phase of an acute crisis during the last four years, let’s say. The first buildings in Předlice collapsed in 2010, and miraculously no one was harmed in the beginning. Several nonprofit chains have their branches in that town, and they are the recipients of big subsidies to aid impoverished Romani people in the town and to work in Předlice specifically. The Czech Government Agency for Social Inclusion also worked in Ústí for several years until recently. Had those organizations been playing their watchdog role, they would have done their best to draw attention over the past few years to the catastrophe in Předlice, they would have informed the public what is going on in the ghetto, they would have openly criticized the local politicians responsible, they would have done their best to pressure them to start addressing these matters. That did not happen – rather, the exact opposite happened. When we read the online presentations of these organizations from that time period, what we read is how well everything is developing, how social integration is succeeding in the town, success after success, cooperation with the town is good, a bright tomorrow is in reach. Not only is there no hint of criticism, there is not even a description of the actual situation. That’s what I call anti-watchdog behavior. At a time when things are as fishy as they can be, when there is a threat of acute danger, the anti-watchdog wags his tail and frolics about to such an extent that he succeeds in convincing some people that everything is in order, that nothing is going on. A real watchdog would have to bark if something were wrong.

Q: How do you believe the nonprofits are behaving now, in the time of this particular crisis, when their clients are the targets of pogroms?

A: It varies. In Duchcov, for example, we are collaborating with a small local nonprofit, Květina ("Flower"), which provides social services and recreational activities for children and youth. With its modest resources, it is doing its best, everything in its power, to stop this onrush of hatred. It is doing the very maximum. Naturally, Brno is also fabulous. Nonprofits in Brno joined the Blokujeme! platform and the collaboration with them is brilliant, we understand one another. The platform’s events in Vítkov were primarily a result of the good work and organizational capabilities of people from Brno, they are doing the maximum as well. I understand that the nonprofit organizations are very often under enormous pressure. It is not easy at all to win money for their operations through the subsidy tender process, and municipalities are not interested in nonprofit watchdog activities. The Květina civic association in Duchcov has stood up against the principle of collective blame that has been applied to the Romani community in the town, and members of that community work for that association. Ever since they took a stand, the association has faced animosity on the part of those representing local government. Even though the association is one of the social service providers there, it will evidently be facing problems that could shut it down in its current form. This isn’t just about nonprofits, though – civil society has long been silent about the current wave of anti-Roma hatred and violence, although that may be slowly changing. The first groups to speak up against the current wave of pogroms were the Scouts and a Sokol organization in Brno, and representatives of some churches and religious communities joined them. At the start of June we published an open letter, calling on civil society to support us. The Czech Government Agency for Social Inclusion and the Czech Helsinki Committee responded, issuing statements against the pogroms and in favor of nonviolent events supporting the Romani people facing these hate marches. Recently these protests have taken place all over the country. Anyone can help in the location that is nearest to them, and that support can take various forms. It is completely ok that some people do not want to expose themselves to the increased risk to their personal safety that is definitely involved in participating in an assembly to support the Romani community at the same time as a pogrom is being attempted against it. The Blokujeme! platform also needs other forms of assistance. We need people who know how to write, people who can loan us sound systems, vans, supplies for holding the "children’s days", there’s a lot to do.

In the past, of course, we have also encountered some nonprofits whose behavior was downright harmful. Their social workers abused their positions to convince the Romani people targeted by these events, ahead of an anti-Roma demonstration or march, to conform, to be passive, to do nothing. "Nothing’s going on, lock your doors and watch television, the police will take care of everything." That advice is the road to hell.

Q: Why have you chosen your particular tactics? Wouldn’t it really be safer not to hold another event on the day of a march and to leave the space to the police?

A: Decidedly not. The racists in these marches are striving for one of two things. They either want to have a battle, a clash – with the police, with Romani people, it doesn’t matter with whom – or they want to march right up to a building where they can shout anti-Roma slogans to terrorize the Romani residents. If they achieve one of those options, they consider the march a success. We have observed how they always return to the same places to repeat their marches, that’s probably part of their tactics – it’s easier to repeat an action in a place where you organized it before, you know it there, you have contacts, etc. Our activities are essentially focused on preventing both of these options – both physical clashes/violence, and a situation in which a mob of racists is chanting "Gypsies to the gas chambers" beneath a Romani family’s window. Most of the Romani people who have experienced something like that say it was the worst experience of their lives – the danger, the hatred, the humiliation. The mob outside is shouting while the father of the family is sharpening a knife at the kitchen table and the crying children have locked themselves into the bathroom with their mother, who is armed with a frying pan. Who in this country cares about that? Who even cares about what the victims of these hate marches experience? Where will we ever read a description of that? Where is the help and support for these people? We base our actions on the understanding that when we occupy a space, then an anti-Roma mob cannot occupy it. That is the basis of our tactic.

Q: Your events are legal, you announce your assemblies to the authorities. You block off the streets where Romani people live.

A: Yes, that’s what we are working with. We are not directly blocking anyone in anything, we are just using our right to assembly and our good knowledge of these situations. When we know a crisis has broken out somewhere, that hate is on the rise, then we announce our own assembly in support of good relations between neighbors in that place. We choose the location so that we can act as human shields in case a pogrom is attempted. Sometimes it works. We were the first to announce assemblies in České Budějovice and Duchcov, even before the neo-Nazis did. When the racists later tried to announce marches down the streets in those towns where Romani people live, the authorities could easily refuse them because we had already announced our own assemblies in those locations. The African-American Christian activists did something similar in the American South during the 1950s – they set up their podiums at the destinations of Ku Klux Klan marches.

Q: How do the police like your activities? What kind of relationship do you have with them?

A: Well, it varies, it depends. You must realize that from the point of view of police tactics, our activities are basically an additional problem. There are more people on the streets and it complicates what is already a complex security situation. The police must deploy more people just to keep an eye on us. On the other hand, they can rely on the fact that our events are always nonviolent, and we share their goal of preventing clashes. Often we are playing the role of yet another anti-conflict team, our volunteers naturally enjoy greater trust in the community and are in a better position that the real police anti-conflict teams. It also depends on who is leading the police operation, which specific police commanders are in charge of which demonstration. Sometimes we agree on everything calmly, we help one another out, we do our best together to make sure everything turns out well, that there is no physical conflict. At other times, other commanding officers seem to have evaluated us as an undesirable risk and the police have actively tried to trip us up, they are able to really complicate our activities in support of a local Romani community. We occasionally faced that kind of pressure during our events in support of the Romani community in Duchcov. We’ve already organized four such events there, always at the same time as an anti-Roma march was taking place. We have had to face, for example, situations in which we had arranged for our usual organizers to be easily identifiable to the police, but once the assembly began, we suddenly realized that someone else, not us, was trying to provide that organizing service in the same space – there were Romani people we had never met before running around in bright orange vests as if they were the organizers of our event. This created chaos and confusion at our demonstration, of course, it greatly complicated our management of our own demonstration. Those participating were unable to tell who the real organizers were, and neither could the police anti-conflict team, whose members immediately came to me and complained that we were supposed to have just one way of identifying who the organizers were, either through armbands or through orange vests, but not both. However, it turned out that these other "organizers" had been created by a police commander in charge of liaison with minorities, and they were working at our demonstration under his command. It is very difficult for us to withstand such a situation, we don’t really know how to work with it. Now we know in advance that it might happen and we are doing our best to anticipate such a scenario, but as I said, it always depends on the specific people involved.

Q: Of course, the police so far have succeeded in protecting the people who are being targeted by the racists’ hatred.

A: Recently I have become greatly aware of the fact that we are basically relying on the police to a great degree, we are counting on them to have our backs, to protect us. During many of these anti-Roma demonstrations, police riot units have been the only thing standing between the aggressive mob and the Romani families. At the same time. I believe it is not possible that they will always be able to keep these mobs under control. The anti-Roma demonstrations are happening with increasing brutality, frequency, and strength. Sooner or later, one of these marches will end in catastrophe. The police will not succeed in keeping the mob under control, the racists will assault Romani people, there will be a massacre. The pogrom will be accomplished. We must seek different paths for addressing all of this than we have used so far. The current and past strategies and tools for addressing Romani racism and poverty used by some majority-society people have completely, totally failed. Anyone who doesn’t see this is simply blind.

Q: The anti-Roma demonstrations are coming in waves. The current wave, which is far from over because it is part of the election cycle, is already one of several in a row. How is this wave different from the previous ones?

A: What is new, very dangerous and very serious is the involvement of young people in these anti-Roma sprees. Primarily during the demonstrations in České Budějovice they were highly involved, they comprised a significant proportion of the aggressive mob, boys and girls. This basically isn’t that surprising – for example, the high school student elections organized by People in Need last year in northern Bohemia were won by the DSSS. It did surprise me that the recent anti-communist protests in České Budějovice were supported by hundreds of students, while the anti-Nazi activities and protests were supported by just a handful of them. More young people participated in the attempted pogrom than in the anti-Nazi events. It is possible that not all of the students who protested against the communists were democrats or promoters of a tolerant society. Anti-communism is very widespread in racist circles.

Q: How does education on the topic of extremism – fascism, neo-Nazism, racism – work in this country? What do students learn about pogroms? What do they learn about Romani people as such? Have the schools in which the student elections were won by the DSSS taken any specific measures to change their instruction on these issues?

A: We have long known that anti-Roma marches and violence are not a phenomenon of small groups of neo-Nazis, but a far larger problem, that of the involvement in and support for these marches by so-called "decent, normal people". We have been talking about this since 2011, when ordinary citizens comprised the hard core of the anti-Romani demonstrations in the Šluknov foothills and elsewhere. We are glad other people are noticing this now, there is a need to start working on this, but decidedly not by offering greater repression of Romani people as a "solution" to calm the racists. Repression will not solve the problem of racism or of Romani poverty – it deepens and escalates those problems.

Q: It is true that the municipalities where anti-Romani demonstrations take place often respond by beefing up their repressive measures, introducing various "zero tolerance" policies, etc. We sometimes even hear from municipal representatives that the Romani people themselves are to blame for these attempted pogroms, not racism.

A: Exactly. It’s completely upside-down. In the places where manifestations of anti-Roma hatred take place, where there is organized group violence against Romani people, they need to realize that hate violence doesn’t have to be physical, it can also be verbal. A mob chanting anti-Roma slogans is nothing less than the group perpetration of anti-Roma violence. Municipalities and other institutions are responding to these events, to this impetus, with repression against their Romani residents. They are beefing up the police presence, they are starting to build up a Romani police force and various supervisory services, etc., they are beefing up the CCTV systems in the Romani ghettos, they are starting to undertake various monitoring measures. I understand that measures like these please the local antigypsyists who are involved in the anti-Roma demonstrations. Such measures are a partial concession to their demands, it gives them the feeling that their anti-Romani demonstrations were not in vain, that they have fought for and won what they were after, that the local government shares their view of the situation, in which the guilty parties are the "evil, inadaptable Gypsies" and the only thing such "trash" understands is the whip. Naturally such measures do not improve these local situations, the real solution lies elsewhere. It doesn’t lie in CCTV systems or fines. Those measures will not reduce hatred and racism against Romani people. On the contrary, enhancing repression increases suffering and the subsequent radicalization of people in the Romani communities.

Q: How do you see the problem of radicalization in Romani communities, primarily among boys or young men, overall? At this point is there a dangerous escalation of negative sentiment underway?

A: Yes. In addition to radicalization, anti-white racism is also rising in the communities that have been targeted by these anti-Romani marches, unfortunately. This is a logical result of a situation in which a mob of your "white" neighbors chants "Gypsies out!" or "Let us at them!" beneath your windows, or even fights with the police to get to you. It’s logical that this will not strengthen your love for the people in that mob. I have been involved with Romani communities for a long time, and what I have had the opportunity to experience and see during the past half-year I have never experienced before this – I guess I never believed it would have been possible. The Roma are afraid. Their trust in majority-society institutions is constantly falling. Many Romani communities are building up militias. The habit of being constantly armed is spreading. There is a risk that such groups will not be used just to defend their communities when they are at risk, but that they could be used to take revenge. Once again, I repeat, this is an unavoidable result of the attempted pogroms, of the hatred against Romani people, of the repression of them. We know every group that has ever found itself at risk in a situation similar to that in which the Romani people find themselves in the Czech Republic has always behaved this way and is behaving this way now. I also believe a Romani organization similar to the Black Panthers will soon emerge here.

Q: Doesn’t that strike you as dangerous and extreme? Violence begets violence, that’s no solution either.

A: It strikes me as very extreme. It could end up very badly. Once again, I repeat, there is a need to really begin solving the problem of Romani poverty and the problem of anti-Roma hatred in a different way than we have been addressing these problems for the last 20 years. Those solutions have failed. There is a need to immediately abandon these dysfunctional integration models and seek new ways forward that will work. There is a need to break down the status quo that has been conserved and has dominated the issue of Romani integration for the past two decades. We must get out of the dead-end street we are in, because it is actually leading us closer and closer to the edge of a cliff. Naturally, it’s very hard for everyone who led us into this dead-end street, even though they had the best intentions at the start, to acknowledge this. Those people keep avoiding a change of route, but the cliff is already in sight, and more and more people are seeing that this road will lead them over the edge.

Q: Is there anything about the current events we are discussing that is perceived by the majority part of society as extreme, but is really more about an effort at emancipation that about excessive behavior?

A: What is "extreme" changes depending on the situation and the time. The word "extremist", as we know it today, was disseminated into the world through the jargon of the American security services during the 1950s. They used that word to describe the preacher Martin Luther King, Jr. His home organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was labeled an extremist organization in the American South. The demands made by King and his fellow activists – mainly, the complete abolition of all forms of segregation, the inclusion of African-Americans in decision-making on matters that concern them, etc. – were considered extreme in those days. King analyzed his alleged "extremism" in a famous interview for Playboy magazine (which is available in Czech translation). The perception of him completely changed a few years later, when Black radicals like Malcolm X or the Black Panthers appeared with their demands and their methods for achieving them. At that moment, the American state and its security forces stopped viewing Dr King and the method of nonviolence as extreme and began negotiating about his demands. Eventually they accepted them. Martin Luther King, Jr., who had initially been labeled an extremist, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Mahatma Gandhi in India and Nelson Mandela in South Africa are similar examples. In the Czech Republic today, people still do not want to accede to measures and solutions of the King type – these seem too daring and extreme to them. The demand that Romani communities be able to influence the form and shape of their own integration, or that they be able to influence and monitor the flow of monies used for that purpose – this seems extreme. It would mean stopping the flow of those resources into repression, into CCTV systems, into segregated schools, into the nonprofit chains, etc. That would bring about big changes. The social integration policies and their tools would have to change from being dysfunctional plans designed by "experts on Romani social integration" into measures based on the needs of Romani communities. They would have the potential to change this critical situation.

It seems, however, that some sort of very strong impulse is needed for such a change. We are probably forced to wait for Malcolm X, or for someone to be injured – or, God forbid, killed – by these pogroms.