"Rukeli", or Prisoner Number 9841: Boxing champion Johann Trollmann was yet another victim of forced sterilization and racialization

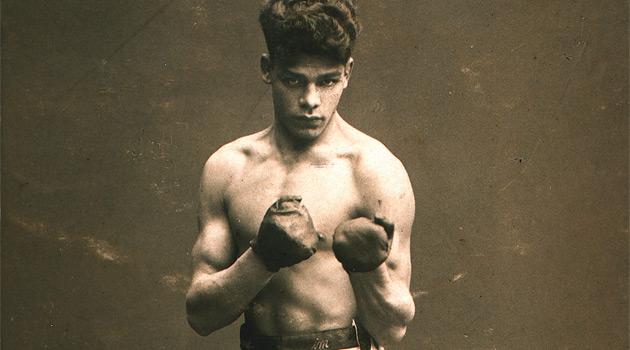

“Straight and strong as a tree trunk.” Those are the characteristics that led Johann Trollman, a gifted boxer from Hannover, Germany, to be given the nickname “Rukeli”, which in the language of the German Roma and Sinti means “tree”, while Nazism was still on the rise.

His life story has inspired the German theatrical director Rike Reiniger to produce the play “Gypsy Boxer“. Why does it speak to people still today?

Trollman was born in 1907, had eight siblings, and began his training as an amateur boxer at the age of eight. When he turned 15 he won a regional championship and became a member of the Heros Hannover boxing club.

Rukeli excelled at a boxing technique that was uncommon at the time. He defeated his opponents not just with his dynamic, swift blows, but also involved his legs and circled around them – in the words of the future boxing visionary, Muhammad Ali, he “flew like a butterfly and stung like a bee”.

This was the opposite of the boxing style that was predominant at the time, which appeared rather cumbersome in comparison. Thanks to his boxing gifts and specific technique, Rukeli, who also had the face of a Hollywood star, won the German championship in the middleweight category in 1933, beating Adolf Witt.

However, this meant that a champion of this sport, which was considered by Hitler to be one of the most “noble” of athletic disciplines and one in which the “Germanic soul” was said to display itself the most, was now a Romani man. From the perspective of the Nazi chiefs, that outcome of the match, which had gone 12 rounds, could not be allowed to stand without some kind of response, given Rukeli’s origins.

The referees, therefore, despite the course of the match having been unambiguous, failed to declare Rukeli the victor. Of course, that sparked vocal disagreement from those spectators who were enthusiastic over his performance, and he eventually was awarded the title of champion of Germany.

Several days later, however, he was stripped of that title for his “un-German boxing style”. The public could do nothing about it.

Here I am – a “white” man

Influenced by these events, Rukeli decided to approach his next match as a theatrical performance. What else, after all, had the organizers of that high-level boxing competition done hand-in-hand with the Nazis than turn it all into a farce?

He appeared inside the ropes with dyed blond hair and a face powdered with white flour. His message was clear: Here I am – a “white” man. Will you all now finally respect me as your equal?

The gesture was a desperate mockery of the ideology of the Nazis, which was primitive, but for which many were willing to manipulate the rules of fair play, their own values, and other people, and the world outside the boxing ring was also beginning to follow such deformed rules more and more. In June 1935, Rukeli married Olga Bilda, a German woman, who later gave birth to their daughter Rita.

A few months after their wedding, the Nuremberg Race Laws took effect, which for most Romani and Sinti people foreshadowed a tragic end, and those who were seen as having wanted to “taint” the blood of the Germans through such marriages found themselves on the wrong side of the law. Rukeli was therefore forcibly sterilized at the end of 1935.

To save his daughter and wife, Rukeli decided to divorce Olga. He was subsequently imprisoned in the Hannover-Ahlem work camp for several months and in 1939, just after the Second World War broke out, he was drafted into the Wehrmacht.

Rukeli then fought with the German Army in Belgium, France, Poland and the eastern front, where he was injured. In 1942, just like all other “gypsies”, he was excluded from the Wehrmacht for “racial reasons”.

Of course, that did not mean Rukeli would be at liberty. In June 1942 he was arrested by the Gestapo in Hannover and deported to the Neuengamme Concentration Camp near Hamburg that October.

From that time forward he was called “Prisoner Number 9841”. Not long after Rukeli’s imprisonment, however, Albert Lütkemeyer, commander of the SS at Neuengamme, who had once been a boxing referee, recognized him as the former boxing champion.

This discovery meant that after performing forced labor all day with the other prisoners, Rukeli had to spend his evenings entertaining local SS men by boxing them, even though he weighed 30 kg less than he had during his boxing career. He would have soon died of this treatment if he had not been saved by a group of his fellow prisoners, led by André Mandryxcs, who did their best to take advantage of their personal contacts to protect selected people.

Thus it was that the official death of “Prisoner Number 9841” was recorded as 9 February 1943, while Rukeli swapped his identity for that of a dead prisoner whom his fellow prisoners then insisted was him. Using his new prisoner number, Rukeli was soon transported to the camp at Wittenberge.

A mass grave

Rukeli did not escape recognition after being relocated to another concentration camp and was again forced to fight matches that had nothing to do with the dignity and fair play that are meant to be typical of boxing as a discipline. He won those matches nevertheless.

One fight with a hated fellow inmate in the position of a local kapo, Emil Cornelius, would prove fatal to him. Although Rukeli’s health was in a miserable state, he won the fight.

Cornelius took revenge for his defeat by making Rukeli work until he was completely exhausted, and then, when the helpless man could no longer defend himself, killed him by striking him with a baton. Rukeli’s body was then tossed into a mass grave along with many others near the camp.

If it were not for the testimony of Robert Landsberger, a fellow prisoner, the circumstances of Rukeli’s death would have been lost to history. Landsberger eventually managed to survive the concentration camp at Wittenberge and after it was liberated, testified that he had been an eyewitness to the murder of Rukeli.

His testimony was recorded and remained in the archive of the Neuengamme memorial site for many long years until Rukeli’s story again came to light. This tale of the absurdity of an ideology based on the principles of collective guilt, hate, and a sense of superiority – one which, even after such harrowing experiences, has not yet disappeared from many heads and hearts to this day – continues to inspire us now.

The 2016 Czech premiere of the play “Gypsy Boxer” was staged as part of the commemoration of the first mass transport of Romani people from Brno and its surroundings to the Auschwitz Concentration Camp. The unique one-act play was also performed during this year’s commemorative ceremony at the National Memorial in Prague on Vítkov Hill, organized by the Museum of Romani Culture on the occasion of European Roma Holocaust Memorial Day.

In 2003, Germany’s Professional Boxing Association officially recognized Johann Trollman as the 1933 boxing champion in the middleweight category. The City of Hannover, in 2004, named one of its streets Johann-Trollmann-Weg.

Since 2011 a sports hall in Berlin’s Kreuzberg neighborhood has also been named after him. Other monuments to this brave athlete, whose life story has also been told in the form of books (e.g., Johann Trollmann and Romani Resistance to the Nazis by Jud Nirenberg in 2016), films and theatrical productions, are on view today in Berlin, Hamburg and Hannover, as well as in Canada and the USA.

First published in Czech and Romanes in Romano voďi magazine.

Romanes version available here: http://www.romea.cz/cz/romano-vodi/rukeli-vezen-cislo-9841.zivotni-pribeh-slavneho-boxera-johanna-trollmanna