News server Aktuálně.cz reports that a group called the Platform for European Memory and Conscience (Platforma evropské paměti a svědomí) has published a unique collection of 30 stories introducing heroes who have resisted terror and violence. The collection, entitled So We Will Not Forget (Abychom nezapomněli) will be officially launched tomorrow and includes heroes from 16 European countries, including two Czechs – Josef Bryks, a Royal Air Force fighter who was tortured to death by the communists, and the executed politician Milada Horáková.

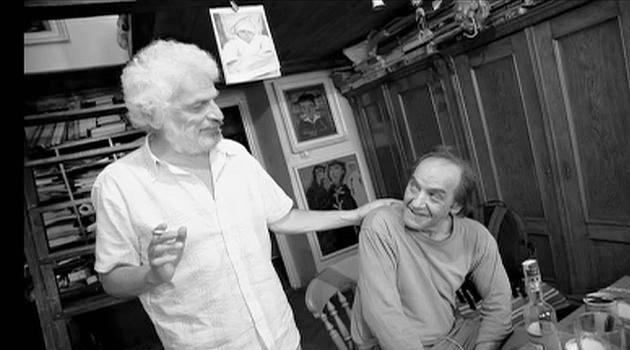

The collection also includes Slovak representatives such as the sociologist Fedor Gál, a man who was born in the Terezín concentration camp during WWII, was a dissident during communism, and relocated to Prague from Slovakia after the break-up of Czechoslovakia. Gál plays two roles in the collection, both as one of the 30 heroes and as the author of one of its pieces.

Gál’s contribution is about his father, who died during a death march. "I am opposed in principle to putting myself in the role of hero, I am really very far from one," he said during an interview for Aktuálně.cz, which news server Romea.cz brings you in translation.

Q: Are you concerned that extremism is gaining strength?

A: I am concerned, to tell you the truth. I am feeling more and more anxious about people. During my life I have been harshly confronted several times with very evil people – anti-Semites, racists. In the Czech Republic and Slovakia there are strong resentments that remind me of the 1920s and 1930s. I am anxious because, for example, the neo-Nazi Kotleba won the regional elections in Slovakia with enormous support. I am basically sick over the nationalist drivel of Tomio Okamura, to say nothing of Klářa Samková, who is seeking a seat in the EP by taking a racist stance on migrants – and Okamura doesn’t forget to emphasize that she is not a Gypsy, that her [first] husband just happened to be one…

Q: Who did you have your harsh confrontation with?

A: During the Holocaust, 95 % of my family perished. I did not expect that when I entered politics after the fall of the communist regime I would be so massively confronted with anti-Semitism. I received very evil anonymous messages and threats. Even today, if the Slovak media features me, if I give an interview or write an article… an unbelievable discussion is always unleashed. Over the past few years I have been filming a documentary about Natálka from Vítkov, who was burned in an arson attack. She is from a clean, good, integrated Romani family… all their girls are doing brilliantly in school… but despite this, they have been unbelievable attacked by those around them just because they are Romani. Several other minorities are in a similar situation, surrounded by aversion, hatred and mistrust.

Q: As a Slovak Jew, have you had any bad personal experiences with Czechs?

A: I have been living in the Czech Republic since the break-up of Czechoslovakia. During all that time I have never encountered open anti-Semitism here, unlike in Slovakia. I am sad, for example, that one of the most successful films about Slovakia, "Obchod na Korze" (The Shop on Main Street – 1965), which won an Oscar, has never even been screened there. In a few days we will be commemorating the 70th anniversary of the escape of two Slovak Jews, Rudolf Vrba and Alfréd Wetzler, from Auschwitz. It was thanks to them that the world learned what was going on in that largest death camp. However, in Slovakia there is silence about their fantastically heroic deeds. Vrba’s book about his escape from Auschwitz has never been published there, while in the Czech Republic it has been published twice.

Q: Sometimes I ask whether the heroes who perished in the fight against totalitarianism might seem in the eyes of some people today like naive idealists who laid down their lives for nothing…

A: The heroes we are talking about never wanted to be heroes. They just wanted to live normally. They did not yearn to die in a concentration camp or on a death march… or to be hanged as the result of a political trial. However, when they found themselves in situations in which their lives or the the lives of their loved ones were at stake, or even when "just" their character or honor were at stake, whether during the uprising in the Warsaw ghetto or in the death camps of Auschwitz, Treblinka or Sobibor… then they stood up to that evil because they couldn’t do otherwise. Moreover, if you had ever asked any of the hundreds of passersby on the street in those days whether they wanted to be heroes who sacrificed their lives for an idea, or for others… everyone would definitely have told you to go to hell.

Q: When you write that we should not forget our heroes, should we take this as an appeal or as a warning?

A: One should never forget that all of the injustice, pain, trauma, and violence we carry inside us is transferred to our children. They then transfer it to their children. One way to get rid of all this suffering, to free our descendants of these traumas, is to speak about this all out loud, to be open to the past. If we forget about those who managed to achieve something, who were brave, who sacrificed their lives, who suffered for us, on our behalf, then we erase everything they did. It’s like killing or murdering them all over again.

Q: Do you believe there is a difference between a nationalist like Marian Kotleba, who has been elected governor of the Banská Bystrica Region in Slovakia, and the communist Oldřich Bubeníček, who is the governor of Ústecký Region in the Czech Republic?

A: It’s six of one, half a dozen of the other. For me these people pose a real danger. I understand those two ideologies to be each other’s brother and sister. One is the ultra-left and the other is the ultra-right, but in reality, both are connected at the same point in their trajectory. In my eyes, the Kotleba in his "National Guard" uniform and jackboots is the same as the slick Oldřich Bubeníček. I just finished reading a book by Timothy Snyder called Bloodlands [editor’s note: about the Baltic states, Belarus, Poland and Ukraine] which discusses the history of the territory between the two totalitarian empires, Hitler’s and Stalin’s. In those countries alone, 14 million people perished over the course of 20 years as a result of the policies of both dictators. Snyder has carefully calculated the number of victims and discovered that the blame lies 50-50 between the communists and the Nazis.

Q: Isn’t Kotleba a much greater evil than Bubeníček?

A: You may be right. People’s memories of communism are fresher than their recollections of Nazism, which we are sometimes forgetting. That forgetting could be even more dangerous.

Q: To what degree are the democratic parties’ governing tactics pushing voters into the embrace of extremist parties?

A: I disagree with that. I am becoming more and more allergic to those who flatten out and simplify our development over the past 25 years that way, it’s not objective. Didn’t the communists also make their livings on corruption and undeserved privileges? We have a free media today and independent courts… and when corruption is discovered, things usually get rather hot for those involved. Many of them have had to leave the country, others are in prison, others await trial… It is possible that many, many people will never be punished, but it’s not taboo to do so today like it was during communism.