Czech director of "The Painted Bird": All it takes here is to be different and you've got a problem

Here in the Czech Republic, viewers are not leaving screenings of the most-discussed film of Czech cinematography early as the first sensationalist headlines about its screening elsewhere proclaimed was happening. On the contrary – almost 100 000 people have gone to see it in cinemas alone.

The director/screenwriter of “The Painted Bird” did not at all anticipate that would be the domestic reaction. “I am glad to be able say to you all straight up – don’t be angry, forgive me, I estimated that poorly somehow,” is the message Václav Marhoul has for Czech film-goers.

Born in 1960, Marhoul is a director, producer and screenwriter as well as a member of the Divadlo Sklep (“Cellar Theater”) company and the Pražská pětka (“The Prague Five”) ensemble. A graduate of the Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (FAMU), after the Velvet Revolution he worked for seven years as the General Director of the Barrandov Studio and later as manager of the arts association and gallery called Tvrdohlaví (“The Stubborn Ones”).

Marhoul has directed the films “Mazaný Filip“, “Tobruk” and “The Painted Bird”, based on the global best-seller by Jerzy Kosiński, which made it into the main competition of the Venice Film Festival last year. He also signed a contract last year with the prestigious American artists’ representation agency, Creative Artists Agency.

Q: You have dedicated a chunk of your life to filming “The Painted Bird”. How did it occur to you to film that “unfilmable” book?

A: It occurred to me after I read the first three pages, believe it or not. It was such strong reading matter that it awakened my imagination, I comprehended that I was holding an absolutely exceptional work in my hands. Once I finished reading the book I was fully decided that I must film it one day. I read it ahead of making “Tobruk”, and once I had completed that, “The Painted Bird” began to come back into my head like a boomerang, and I decided to take the first step of acquiring the rights to the book. Nobody else in the world had managed that yet.

Q: How long did that take?

A: Exactly 22 months. The contract with the publisher in Chicago and negotiating the details took 14 months of combat that was rather merciless, but I must acknowledge that it was also quite fair. For example, one of my conditions was that they would not have the right to approve my screenplay. Yes, they could express their opinion of it, but not give the final approval. Eventually they agreed to that.

Q: Would you begin making “The Painted Bird” again if you knew it would take you 11 years, that you would be writing 17 different scripts, and mainly that it would be so difficult to raise money for it? You could have made three films during that time, for example…

A: Maybe… but that’s just speculation. If you get your hands essential material of this kind, you never know exactly how long it will take to produce. I didn’t suspect it would take 11 years, either. Sometimes I tell myself that our ignorance protects us. You don’t know what will happen tomorrow, you go day by day, month by month, year by year, and eventually you arrive at your destination.

Q: “The Painted Bird” is not in color. The 35-millimeter format is also not traditional. Was your aim to make the film appear to be from the old days? Does the black-and-white format evoke something for a viewer that color film cannot?

A: Color would have literally ruined this film. From the beginning I wanted the story to look like a real one, and I realized it was exactly color that would literally rob the film of its truthfulness. Black-and-white is also more abstract, and thanks to that, it aids the viewer’s own imagination. Have you seen “Schindlers’ List“?

Q: I’ve seen it.

A: So, imagine if “Schindler’s List” had been in color. I think that would have been an absolute catastrophe. However, there are many fabulous dramas about the war that are filmed in color and it doesn’t hurt them at all. The English film “The Long Day’s Dying“, for example, or the Soviet film which in my view is also the best such film, from 1985, “Come and See“, by Elem Klimov. Nevertheless, “The Painted Bird” is not a war drama, it’s about a universal message, it’s rather a psychological testimony about the creatures we call human beings.

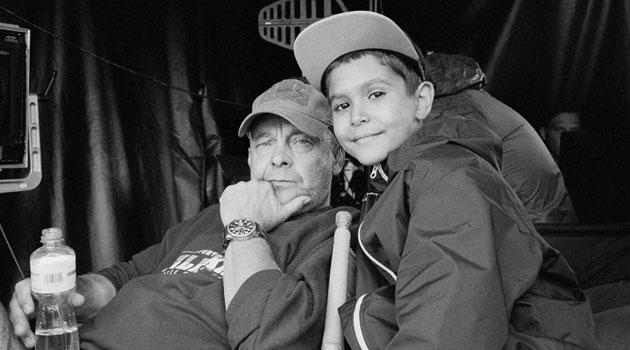

Q: You’ve turned an unknown boy into a globally famous actor. Are you still following the career of Petr Kotlár as an adolescent?

A: Certainly, I know what’s going on around him. We must realize he’s still a child, a 12-year-old who goes to school.

Q: Do you advise him when he chooses roles?

A: To tell you the truth I addressed that just once, because Péťa’s dream was to perform in the TV series “Ordinace v růžové zahradě” (“The Surgery in the Rose Garden”) and Radim Fiala, who plays the character of the doctor, aided him with that at the time. That was a catastrophe, because he was offered a role, even if I’m exaggerating a bit, of a “stinking cikán” who bullies poor little white boys. I immediately dissuaded him from taking the role.

Q: Did he comprehend why you argued against it?

A: I explained to him how television works and that television is not film. A film does not have as much of an impact on people. Unfortunately, there are some people here – and this is a sad piece of news to deliver – who are unbelievably stupid. A friend of mine who plays a negative character in a TV series was recently beaten up by people who believed he is exactly the kind of person whom he portrays in the series. We can draw on past examples as well – when “Nemocnice na kraji města” (“Hospital at the End of the City“) was being broadcast, the actor Vinklář was refused service in a butcher shop with the words: “Dr Cvach, we won’t sell you anything.” When, in that same series, the character of Ema, the housekeeper to the head physician, Sova, passed away, people sent cake or slippers to the television station for him. So in other words, if Péťa were to accept such a role, as an aggressor, then some people would believe he’s one in reality as well. This wasn’t about me forbidding him to do it, I have never forbid him to do anything that way, but I explained to him that he actually should not render such a role.

Q: What do you think, as a director, of the depiction of Romani people in Czech films and serials? Is it stereotypical, or not?

A: In the area of Czech film there is just one Czech director dedicated to this, Petr Václav. He has made two feature-length films and I believe they were made honestly and not stereotypically. I will not name another colleague of mine, a director who made a feature-length film where one of the roles was meant to be Romani, but he was so frightened of working with a Rom that he cast a white actor in brown face. That was a terrible event. Television series, however, probably have to succumb to stereotypes, they want to accommodate the majority taste. According to sociological surveys, Romani people are not the favorites with the majority here. Most people unfortunately even apply the principle of collective blame to them.

Q: What would have to happen for Romani people to perform roles here that are not based on their ethnicity? Like in the American productions where African-Americans play lawyers, doctors, police officers …

A: When I cast Péťa in “The Painted Bird” I wasn’t thinking along those lines. I have my own approach. A big Romani community lives here in Český Krumlov. I have many brilliant friends among those people and I think this is above all about personal experience, about comprehending that there are differences among us that do exist, just as they do among all other people. However, for that to change in this society is going to take a very long time. [Public broadcaster] Czech Television took an unbelievably big step forward with the “MOST!” series, I believe that represents enormous progress. I dare say a series like that did manage to change people’s opinions or thinking. For example [the Romani actor] Mr Godla played a positive role, so [commercial broadcaster] TV Nova will follow suit. Television stations want to be inconspicuous that way, so if an actor falls into a category, and Mr Godla has fallen into the category of positive roles, then he will stay there, because viewers are accustomed to seeing him like that. However, if it were a negative category, then nothing could aid him, because audiences don’t comprehend that the people on their screens are just actors.

Q: How do you personally perceive the current position of Romani people in the Czech Republic?

A: People frequently tar all Roma with the same brush, period. It’s classic xenophobia, in some cases it goes as far as discrimination. However, we must also be straight with each other and say that some Romani people are themselves to blame for many things. It’s a terribly complex matter. This is not just about Romani people here, though, the same goes for Germans, or for Americans, because Czechs are bothered (although the Roma are also Czechs) if somebody is shouting loudly somewhere, for example, or arguing – it bothers me, too. If I’m on the tram and 20 jolly foreigners get on and bellow as if the world belonged to them, it’s just not pleasant. The same thing sometimes happens with some Romani people. They then create a bad reputation for those who do not behave that way. I have also experienced this, of course, with white people several times, but it’s more difficult with the Roma, because anybody can then think “You see, we always did believe that this is their behavior.” Romani people are not aware that if some of them behave like that, they a priori confirm all of the prejudices the majority holds against them.

Q: In the film “Tobruk” your heroes have doubts, they are buffeted by emotions, it goes so far as to make them anti-heroes. Why?

A: During war there are no heroes, in war you want to survive. That’s what “Tobruk” is actually about, unlike “The Painted Bird”, it is a wartime drama. “The Painted Bird” is not even a film about the Holocaust, its environment and form may be anchored in a certain year, but the film is timeless. However, what’s in “Tobruk” is the reality of how that all actually functions. Things are not really as they are depicted in other films, where the protagonist is a big hero each and every minute and never wavers. That is genuinely not how things work, and I really feel sorry for all those people who believe that war is both hell and great entertainment. It would be enough for them to take a single step into a war zone just once and they would immediately change their opinion.

Q: What is it like for a Czech director to film with stars like Harvey Keitel and Stellan Skarsgård? Did you have to make a confident impression on them, that you knew exactly what to anticipate from them, or was it that your humility with respect to the subject matter and your modesty with respect to the actors themselves convinced them to join you?

A: That’s an unbelievably sensitive question and I’m slightly embarrassed by it. Both are the case, of course. They know whether a director already knows what he wants and how he will manage to achieve it. From me they felt that this was an auteur film, that I was literally living through this film. I worked with them before we began filming them, they saw samples of what we’d already done. From that footage they comprehended what I was about. We always spent the evening before a shoot together, we discussed the roles, the film, so then I had no problem on set.

Q: The film has already been screened at many prestigious festivals and Vladimír Smutný won the prize for best cinematography at the Chicago International Film Festival. It has also been screened with big success in the Czech Republic. What is the life of this film like currently? What kind of plans do you still have for it?

A: This is all just the beginning. In the Czech Republic we are approaching the magical number of 100 000 viewers – if you’d asked me my prediction several months ago and told me so many people would come to see “The Painted Bird” here, I would have believed you’d gone crazy.

Q: Does that mean you’ve broken down a prejudice you held about Czech audiences?

A: I’ve broken it down. I am glad to be able say to you all straight up – don’t be angry, forgive me, I estimated that poorly somehow. In the case of a demanding film of this kind – black-and-white, lasting almost three hours, without dialogue or music – I think my considerations were absolutely rational. Otherwise, we’re currently taking the film around the globe to 36 festivals. We also were nominated for the Satellite Awards in the USA for best foreign-language film. That’s an enormous honor and success. “The Painted Bird” will arrive in cinemas abroad in 2020. For example, in America it will screen in April 2020. [Editor’s Note: After this interview was completed it was announced that “The Painted Bird” is shortlisted for an Oscar in the category of International Feature Film.]

Q: Recently you said: “People believe I’m totally crazy when I say that [“The Painted Bird”] is about love and goodness, even if its format is unbelievably cruel, violent and brutal.” What clue to comprehending your film can you give to those who don’t see your humanist message in it?

A: “The Painted Bird” is built on contrasts. It works, for example, according to the principle that we do not realize the value of somebody or something until the moment we lose that person or that thing. If I were to simplify this, most of the time we don’t realize how important it is to be healthy until the moment we fall ill. We don’t much appreciate it before that. What does suffering mean to somebody who has never experienced it? It’s not until the moment of suffering that one wishes not to suffer. So this story is built on contrasts – you accept the necessity of goodness, of hope, of love exactly because they are absent from this film in an unbelievable way, and you look for them even more as a consequence.

Q: The main hero of the film undergoes a test of character – does the evil others commit against him break the child’s innocent soul? Can violence be excused? For example, the struggle for one’s own life, for self-preservation…

A: The problem lies elsewhere, though – that struggle can actually become a negative position, one of retaliation and revenge. That’s already an absolutely different category. My hero, exactly as you say, is a child with an innocent soul, and he falls further and further into darkness. However, the worst thing about it is, of course, that the child is not aware of this. A child just accepts the behavioral models of the people around him. He is not able to analyze them, as an adult person would. That, again, is an error made by many viewers of “The Painted Bird”, they attribute their own adult experience to him, and that’s absurd.

Q: You most probably saw hundreds of child hopefuls for the main role in “The Painted Bird”…

A: I never held a casting call, I met Péťa Kotlár at the athletic stadium in Český Krumlov and after five minutes I saw that he was the one, and that held true.

Q: How did you come to know Kotlár family?

A: In Český Krumlov. I’ve been visiting there for about 12 years and I always stay in the same room at the Hotel U Malého Vítka – where, by the way, all of my screenplays have also been written. Right around the corner from that hotel, the Kotlárs have their restaurant, Cikánská jizba (“The Gypsy Room”), the locals call it U Cikánky (“At the Gypsy Woman’s”). Sometimes I’d go there for a glass of wine. I think the situation in Český Krumlov is absolutely different than it is elsewhere here. The people in Český Krumlov are not in a trap like the Romani people living at the Chanov housing estate are, for example, or anywhere else in an excluded locality where they may fall into the clutches of loan sharks or other problems such as unemployment and the youth may be into drugs. The vast majority of Romani people in Český Krumlov have jobs, everybody here appreciates that, for example Péťa’s grandfather is a municipal assembly member. His grandmother, Věrka, told me that Péťa was probably not even aware that he is Romani until the age of seven. One day he came home and confided to them that somebody had abused him as a cikán and he didn’t even know what that was.

Q: What surprised you about Péťa’s reaction to filming, or the response of his family?

A: For example, there was a scene where Péťa is floating on a log, and it gets carried away by the river somewhere into the distance, and despite the fact that he’s an excellent swimmer, he was terribly afraid because he was alone on the log. The crew was about 20 meters away from him, his grandmother was running along the riverbank… Nothing could have happened to him, he was wearing a neoprene scuba-diving suit, there were emergency medical technicians prepared to respond everywhere, so even if he had wanted to drown he wouldn’t have succeeded. He clung to the log, he didn’t like it very much. Then we were filming a scene, though, where Péťa was meant to lay down beneath a moving train, originally it was meant to be done by a stuntman, but he said he would do it himself – and then it was my turn to collapse. His grandmother saw no problem with it and said Péťa would do it. So he lay down beneath the train and we filmed the scene behind him, from the left side. First we rehearsed it – the train drove over him more slowly, then they accelerated, there were stunt people there with Péťa beneath the train, and it took us about three hours to rehearse before we were able to film. We saved quite a lot of money, on top of it all, because otherwise it would have been a demanding trick shot.

Q: We can also perceive this film as a parable for today. We can see the fate of refugees in it, the exploitation of them for slave labor, the easy money the smugglers make on them. Is there also something in this film, in your view, that captures the position of Romani people today?

A: I think it captures the position of anybody who is different, it’s not just about Romani people or Jewish people, but about each and every person who gets stuck in the gears of prejudice, xenophobia, or racism. When people have problems, they principally are based in the fact that they are just different. The symbolic scene in “The Painted Bird” is ultimately about that. It’s an allegorical scene that demonstrates the basic message in an essential way. This is a timeless matter, also from that perspective. It doesn’t matter what your skin color is, it’s enough to be different in any respect.

Q: This recent film of yours shows human cruelty and insensitivity in full force. Why do you believe some people reveal this about themselves in such a way? Is it just out of a feeling of power over the lives of others?

A: It’s not just something that shows up, it’s human nature, and each of us has this inside us. Professor Zimbardo at Stanford University demonstrated this with his famous experiment. He turned 24 intelligent, normal, young people from good families into 12 guards and 12 prisoners. He built a fictional prison, with cells, even, and the experiment was meant to last about three weeks. Eventually it had to be closed down after five days because the people in the role of the guards became sadists who began to even mentally and physically abuse their “prisoners”. The experiment created the two basic conditions for such behavior – impunity and opportunity.

Q: Can this happen because of ideology as well? People who were, for example, members of the SS also had families whom they loved, but despite that they murdered and tortured others without compassion…

A: People frequently ask how it was possible that a cultured nation like the Germans managed to commit such atrocities during the Second World War. For example, in Belarus alone there were more than 600 of our “Lidices” burned down and their inhabitants murdered, including the children. That was not just done by SS soldiers, but also by Wehrmacht troops, the so-called ordinary people. Among them were also, for example, the kind of people who two years before had been giving piano lessons in Hamburg and despite that managed to use a flame-thrower to burn a four-year-old child alive. How is that possible? In addition to the two conditions that I mentioned being met – i.e., impunity and opportunity – the psychosis of war was also added to the mix. This isn’t just about killing, because if a victim is a civilian, then we exclusively refer to such killing as murder. Many were traumatized for the rest of their lives by such events – not just the survivors of such attacks, but sometimes even those who committed them, and for many years afterward. Nobody can ever say “I would never do that”, because the human soul is actually a fragile vessel. In order for it not to crack, the individual must have a very high level of morality and very strong principles.

Q: Many people consider the Second World War to be ancient history. What about the victims of present-day wars? Are you able to comprehend the fear of the possible consequences of receiving children or young people from those regions here in Europe? How can we face that fear and the populists who feed it? Is receiving such people here a good idea?

A: I don’t know how to face it in the least. The best way would probably be for people to go see those areas for themselves, to see the dead people with their own eyes, the people afflicted by war, but that is the last thing in their lives they will ever do. So here they will sit, drinking beer, eating dumplings, and somehow they will again become abusive, angry, and hateful. The only way to break that down is through actual personal experience. You don’t have to go to a war zone, it’s enough to go look at a refugee camp in Greece, for example. I was there in June because I have long supported UNICEF in the refugee camps in Rwanda where we have had programs for some time. You can’t buy that kind of experience, it’s reality. It’s just like when I was in Afghanistan or Iraq, these are matters that can’t be communicated – but my experience is that nothing will move people of that kind. They’re building a concrete bunker for themselves and they will close themselves up inside it and fearfully peek out now and again, just to berate everybody. Recently on Veteran’s Day a person came up to me in Prague, he looked rather decent, and he said to me: “Mr Marhoul, you’re in the Army, so you’ll have an opinion about this.” Then he asked how we could shoot dead “all the niggers that want to come to our country”. It was terrible. I responded that he should get away from me, that I decidedly would not be discussing any such thing with him.

First published in the magazine Romano voďi in Czech.