The WWII-era suffering of Romani people was not spoken of in the Czech Republic for a very long time. The horrors of the concentration camps were primarily linked here with the Holocaust of Europe’s Jews.

The silence of our leading state representatives about such events was not broken until 1995, when Václav Havel attended the unveiling of a memorial to the Romani victims of the Holocaust at Lety by Písek, and ever since they have been regularly commemorated. It is no surprise that it took more than 50 years for this first acknowledgment.

In Czechoslovakia, Romani people were – and in the Czech Republic, still are – criminalized, marginalized, and ostracized to the fringes of society. When we look back at history, we find that attitudes here toward Roma have displayed a remarkable, unbroken continuity ever since the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed.

In the summer of 1927, a "Law on Wandering Gypsies" was enacted here in response to a scandal allegedly involving cannibalism, legislation that was pushed through the lower house by the Agrarians and Christian Democrats. A census of Romani people was then performed on the basis of that law, and Roma were issued special identification – "gypsy cards".

Traveling was made significantly difficult for Romani people, as municipalities could deny them entry into their territories and the authorities could take their children away. They were considered inferior, excluded from "decent" society, and stigmatized.

It was Czechoslovak President Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, a humanist thinker, who signed that bill into law. Prior to the invasion by the Nazi Wehrmacht and the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, the Czechoslovak Government, of its own initiative, issued an edict to establish disciplinary labor camps "for gypsy families and other wandering persons", which during the course of the following months were transformed into concentration camps.

These steps were vociferously supported by the Czech Agrarian daily paper, "Venkov" (Countryside), which wrote that while they might have concentration camps for political transgressors elsewhere, and while of course we would never take such measures, it would be good to build concentration camps for beggars and gypsies. Humanity should not apply in their case, as everyone must work.

The camps at Kunštát by Hodonín and Lety by Písek were created by a decision of the Czechoslovak Government to meet the demands of Czechoslovak society, which did not want to be bothered by difference and foreignness. The establishment of these facilities was not the idea of the evil German occupiers, whom it might be easier to blame, but the idea of Czechs.

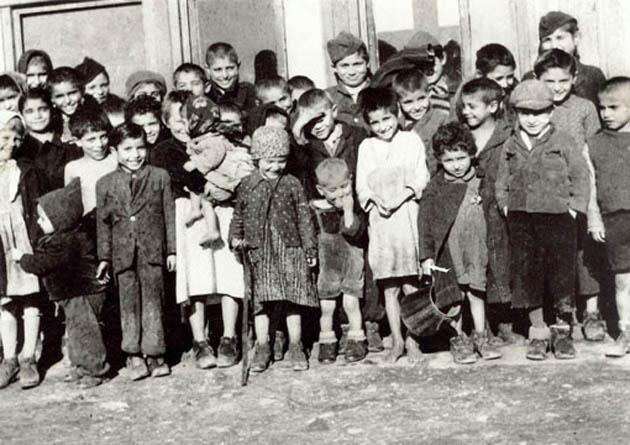

In the "gypsy camp" at Lety by Písek, more than 300 people, mostly children, died. They perished because of the hatred of their fellow-citizens, horrifying hygienic conditions, and inhuman treatment.

The genocide of the Bohemian and Moravian Roma was one of the most thoroughly-performed genocides of WWII. After it ended, less than 600 Roma remained alive.

With the end of the war and the subsequent rise to power of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, it seemed that policies of discrimination and segregation would be replaced with a policy supporting Romani emancipation. A return to the internationalist policy of the Soviet Union prior to WWII and support for minorities was declared.

Romani people were to be integrated into society as full-fledged members. It was no longer beneficial or possible to have a large group of people living a backward way of life in a society building socialism, especially since strong surviving strains of previous political formations continued among them.

High rates of illiteracy and a "low cultural level" were said to be one of the frequent, sad legacies of capitalism. Centuries of oppression and persecution by the exploitative ruling classes were said to have left heavy traces on the character of the "gypsies" living in Czechoslovakia, traces that were being slowly eradicated in our people’s democratic order, where only now they could live as free people.

While the top officials of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia did their best to include Roma into society, results were achieved very slowly. At the same time, the policy of the center clashed with the expectations and notions of local functionaries, who under pressure from the public were advocating a return to repressive politics (it was proposed once again to send the Roma to labor camps, for example).

During 1958, the party abandoned its original position of emphasizing gradual re-education, patience, and the voluntary transformation of the Roma population, defiling itself by giving in to the many years of calls from the regions and the security forces for a bureaucratic, repressive solution to the issue of coexistence between the majority and Roma. Emancipation was once more exchanged for discrimination and persecution.

Instead of supporting the specific identity of ethnic Roma, the Communists began to destroy their culture, just as many others before them had. Traveling Roma had their horses and wagons confiscated and were moved from their communal settlements into anonymous housing estates, where the men often ended up as unskilled laborers.

The state took children away from Romani women and involuntarily sterilized many of them. Those who had previously been considered victims of the capitalist order now were labeled "socially dangerous elements" with the justification that there was no room for people of their kind in developed socialism.

The situation has not changed much to this day. The fascisization of society, including the mainstream (and this is not just about the bizarre figure of Tomio Okamura and his "Dawn of Direct Democracy" movement) is gaining strength here today.

Today, neo-Nazis regularly march hand in hand with so-called "decent citizens" in towns throughout the Czech Republic. Grandmas and grandpas, mothers with babies in prams, schoolchildren all shout "Gypsies to the gas chambers!" together with the right-wing extremists without even blushing.

That is why today, more than ever in the past, there is a need to stop trampling on the Roma and instead to support their emancipation efforts. We can no longer deny them their dignity or treat them with paternalistic scorn.

We can begin at Lety. Since a 2009 decision of the Topolánek government, the commemorative site there has been administered by the Lidice Memorial (Památník Lidice), which is primarily supposed to oversee the commemoration of a different tragedy, the murder of Czechs during Heydrich’s era.

This administrative move involves symbolic oppression: The genocide of Czech Roma is inferior to a tragedy involving Czechs. The Committee for the Redress of the Roma Holocaust, which has long held commemorative ceremonies at Lety, has consistently warned that the Lidice Memorial is administering the territory of the former "gypsy camp" in an inappropriate way.

"We are offended by the gross distortion of the basic historical facts in the texts that are now part of the signage on the walking trail through the site and the entire exhibition there. This distortion is humiliating for the victims of the Romani Holocaust and their surviving relatives. The online presentation about Lety at www.lety-memorial.cz, which is run by the Lidice Memorial with the taxpayers’ money, is a testament to their unprofessional approach and contains many arbitrary, subjective claims, to put it mildly. The same goes for the informational placards posted near the mass grave site," reads the statement issued by the Committee last year. This fact was also noted by Ondřej Slačálek last year in a piece written for Nový Prostor magazine.

The main problem, however, remains the fact that a foul-smelling pig farm has been standing since the 1970s on the site of the genocide and suffering of the Roma. The intention to remove the farm has been previously declared by the governments of Josef Tošovský, Miloš Zeman, and Vladimír Špidla, and yet the farm remains.

The Committee for the Redress of the Roma Holocaust, together with numerous other activists and nonprofit organizations, has been demanding the industrial-scale pig farm be purchased, its operations halted, its facilities demolished, and a dignified memorial be built in its place. Nevertheless, during the past five years, no one has negotiated with the owner about closing it, and the last discussion on how much it would cost to purchase the farm took place more than 10 years ago.

Even though the European Parliament has issued two resolutions (2005 and 2009) asking for the pig farm to be removed, a call that was echoed by the Council of Europe’s Human Rights Commissioner (2011) and the United Nations Human Rights Committee (2013), as well as by other organizations, it does not seem that anything is about to change. Once a year the victims’ memories are honored and the pig farm continues to stink.

From time to time someone official declares that there isn’t any money to buy the farm. Some kind of effort is developed in the media to discuss Lety.

That leaves everyone but the Roma satisfied. It doesn’t matter, though – the main thing is that no pigs are wallowing in their own feces at Lidice or Terezín.

First published on news server Deníkreferendum.cz.